-

Demystify SwiftUI performance

Learn how you can build a mental model for performance in SwiftUI and write faster, more efficient code. We'll share some of the common causes behind performance issues and help you triage hangs and hitches in SwiftUI to create more responsive views in your app.

Chapters

- 0:00 - Introduction and performance feedback loop

- 3:30 - Dependencies

- 10:48 - Faster view updates

- 13:24 - Identity in List and Table

Resources

Related Videos

WWDC23

WWDC21

Tech Talks

-

Search this video…

♪ ♪ person: Hello, and welcome to "Demystify SwiftUI Performance." SwiftUI makes it easy to build complex, powerful apps, offering a large set of features and complex controls like lists and tables. When you're just starting out and your app isn't very complex, performance issues aren't as obvious. but as your app's complexity grows, performance becomes more important. Small issues can get amplified, and code that works well for a prototype might not work as well in production. This session is all about building a mental model for performance in SwiftUI because if you understand how to write fast code from the beginning of the development process, you'll run into fewer issues as your app becomes more complex.

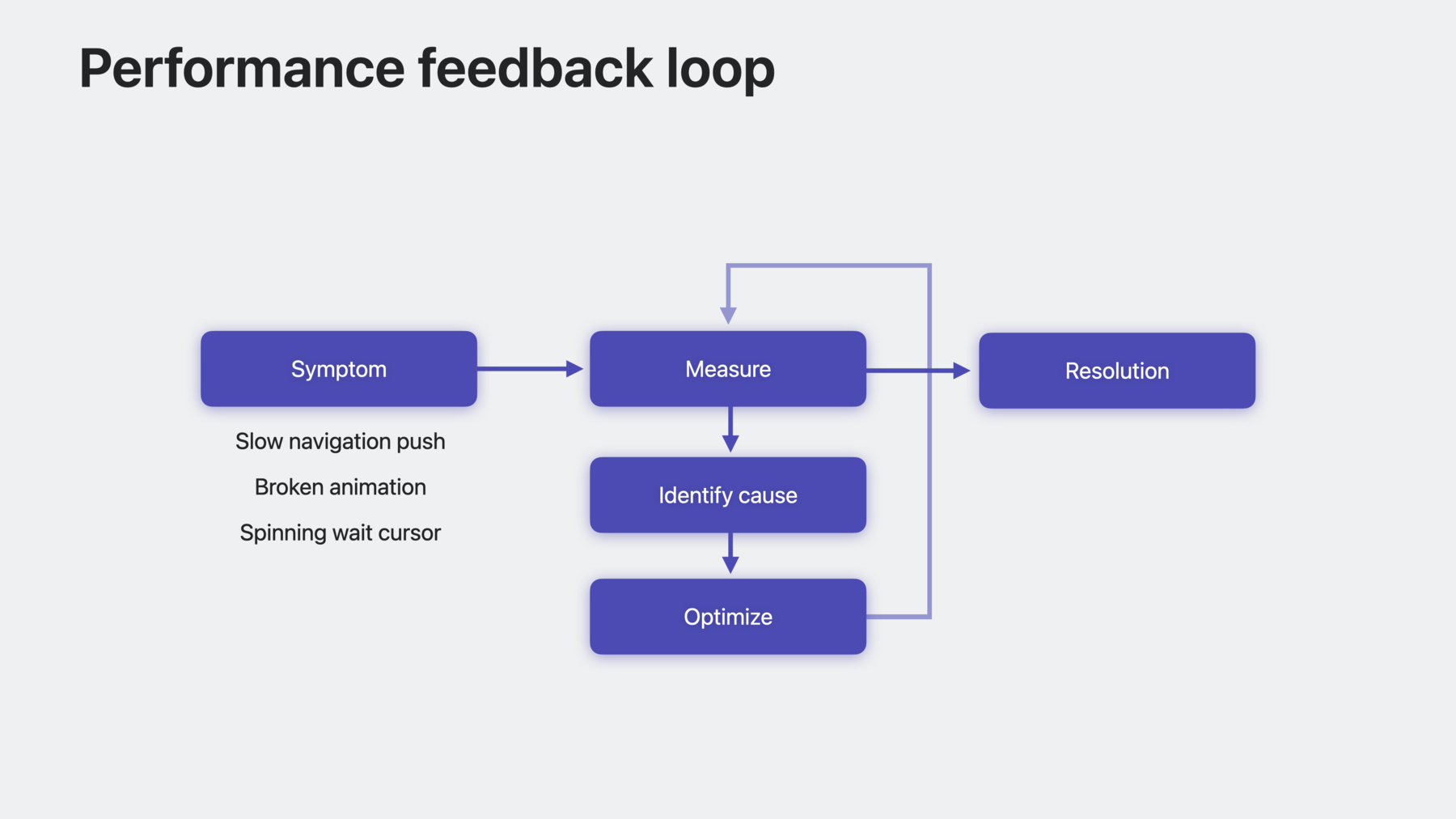

Let's examine the feedback loop involved in addressing a performance problem. Performance problems start with a symptom. Perhaps there's a slow navigation push, a broken animation, or you're seeing the spinning wait cursor on macOS. When you identify a performance problem, the first step towards addressing it is to measure. Once you have measured and verified that the symptom exists, work on identifying its cause. This can often be one of the trickier phases of this loop because it requires an intuition about how things are supposed to work. Bugs arise when your app has an incorrect assumption. This session is about helping you identify the mismatch between your app's assumptions and reality.

After identifying the root cause, fix the issue through optimization. But performance problems don't end after you've found a root cause and optimized your code. You need to re-measure and re-verify any fix you make to ensure that it addresses the issue. This is a good practice for all bugs, but it's especially important for performance. After you've verified that the problem is resolved, you break the loop. This diagram puts this session in context. Ideally, you never end up in this cycle, and you can avoid many performance issues by writing fast code when prototyping. However, it's inevitable that, as your app gets more complex, you end up with performance bugs. It happens to the best of us. And when you do encounter performance issues, it's good to have as many tools at your disposal to triage and fix them. This session aims to make it easier to get through the loop.

This is an advanced session, and there are some prerequisites.

You should have a cursory understanding of SwiftUI identity, including the difference between implicit and explicit identity. It's also important to know the distinction between view lifetime and view identity.

If you don't have these prerequisites, don't fret. The "Demystify SwiftUI" session from WWDC21 has you covered. Today's session picks up where that session left off. Let's go over the agenda. We'll begin with an in-depth discussion of dependencies and explore the SwiftUI update process in detail. Next, we'll move on to a discussion of updates and how to improve the speed with which SwiftUI updates your interface. And last, but definitely not least, we'll discuss identity in list and table. Along the way, we'll take a peek under the hood of SwiftUI and check out several tips and tricks to use when developing. This session is primarily concerned with slow updates to the view hierarchy, but is by no means an exhaustive look at all the performance problems that you might encounter when developing an app. Let's get started with Dependencies.

It's been a few years since the last "Demystify SwiftUI" session, and I've missed working on dog-themed apps. So continuing the theme from that session, I've been working on a new app that lets me keep track of my favorite furry friends and set up some time to play with them. Here's one of the views, a table showing all of the dogs. The app also has a detail view, shown here on iPhone, that shows a bigger picture of each dog, the dog's preferences, and offers a button to set up some time to play. Here's the code for that same view. The view takes in a dog as a parameter and also has an environment property for knowing whether it's play time. As mentioned in the previous Demystify session, this means the dog and the play time variables are dependencies of the view, and another way to show this view is as a graph. Here is a basic graph representing approximately the same view. Each arrow represents a view's body. The dog view produces a stack. And the stack has multiple children, like some text, the scalable dog image, the detail view, and the button. Continuing on, each of those views has children, and the graph continues until it reaches a leaf view, like an image, text, or color. All views ultimately resolve to a leaf view. There are many leaf views in SwiftUI, so I won't be covering all of them here. Check out the documentation for more information. Let's go back to the app. Whenever I'm using the app, I can log whenever I play with one of my friends. I just finished playing fetch with Rocky here, so I've noted that in the app, which updates the button and the image. Rocky's looking pretty happy, but he's definitely too tired to play now. When this data changes in the model, SwiftUI updates this view. Let's explore the update process in depth by returning to the graph and looking at what happens when this change occurs.

Here's our graph again. This is where the previous Demystify session left off, explaining that views form a graph and SwiftUI looks at dependencies when evaluating your code. Let's zoom in and provide a more in-depth look at where those dependencies come from and how you can control them. Each child view is dependent on the view value that gets produced by its ancestor. But there are other forms of dependencies too. Dynamic properties are a common source of dependencies as well. For example, the DogView reads whether it's play time from environment by using the @Environment property wrapper. Therefore, it is dependent both on the value produced by its parent and the value from the environment. If we visualize time on the X axis, the first step in the update process is to produce a new value for the view. This value encompasses all the stored properties of the view, like the dog value and the initial value of the dynamic property. Next, SwiftUI updates all of the dynamic properties of the view, replacing their values with the current ones from the graph. Finally, with the updated value, body runs to produce the view's children. Let's bring in the graph again. This process recurses to update the interface, only updating those views that have new values or other changed dependencies. When we mark Rocky as tired, we get a new dog-- sorry, a new dog struct value, but it's still the same Rocky. Because our data is a value type, a new copy of it is created when it's mutated. And that results in DogView producing new content for the stack, Which updates the stack's children. I'm only focusing on the ScalableDogImage here, but other views may update if they depend on the dog value. ScalableDogImage ends up producing a new image. Images are leaf views, so the rest of the work is done by SwiftUI from here. The process then finishes, and a new rendering is produced. That's how to look at the dependency graph. Let's go over some tips to improve this process. It's important to reduce the updates to only those that are necessary. To understand when a view is updated, SwiftUI has the printChanges method. This lets you print out why the SwiftUI graph evaluator called into a view's body. Let's walk through an example of how to use it. Here we have our scalable dog image, which contains a piece of state. When we tap on the image, the state changes like so.

Focusing on just the image view, if we set a breakpoint in our view's body, from the LLDB console, we can call Self._printChanges by using the "expression" LLDB command. printChanges is a debugging-only facility that gives a best-effort explanation of why SwiftUI requested a view's body. In this case, it's because scaleToFill changed. You can use printChanges to understand whether a view might have extra dependencies. For example, I'm currently running my app and debugging and want to see if this view has an extra dependency. I can add a call to printChanges to this view's body to print every time the view's body is accessed. However, note that printChanges is prefixed with an underscore. In this case, that means, it is never guaranteed to always exist and may even be removed in a future release, so never submit a call to this method to the app store. I'll need to remove this call later. It's only meant for debugging and has a runtime performance impact. If I re-run my app and change Rocky's favorite treat, say, from a biscuit to something else, like a cucumber, I notice a log in the console from our image.

It says that "self" changed. This means that the view value changed, so the scalable image view must have some dependency on the treat, but it doesn't actually need to. Focusing on the code, the view's value only has the scaleToFill member and the dog property. Since scaleToFill is a SwiftUI dynamic property, it would have shown up in the change log if it had changed, so "@Self" here means that the dog value changed. But looking at this view, we only care about the image. So we can eliminate this dependency by instead using just the image. And now, when I change a property of the dog that isn't related to the image, I don't see a log.

The view's dependencies are tightly scoped. If you follow this technique, don't forget to remove the call to printChanges. Let's update the parent view to match. Here's the code for the parent dog view. I need to update the initializer for ScalableDogImage to take in an image, like so. By extracting the ScalableDogImage out, I've reduced the dependencies to only those that matter. I can do the same with the header too and extract it to its own view. This has a number of benefits. This code is now easier to read, and the dependencies of the DogHeader are apparent at its use site. This technique works great for smaller views, but just be careful with very large structs. Not every dependency deserves to be scoped like this. You'll need to use your best judgement.

Fewer updates means better performance when data changes in your app. As we just explored, one way to do this is by reducing dependencies. Try reducing view values to only the data they actually depend on. Another tip is to extract views to reduce dependencies. And finally, the new Observable protocol can also help with dependency scoping by automatically limiting the dependencies to only that which is read. Check out the "Discover Observation in SwiftUI" session for more information.

That was just a quick tour of how to look at dependencies. Let's move on to talk about faster updates. In this section, we'll discuss how to reduce the cost of each SwiftUI update. Slow SwiftUI updates can have a number of negative effects on your app, including reduced responsiveness, such as hangs and hitches. A hang is a delay in responding to user interaction, like a view taking a long time to initially appear. The "Analyze Hangs in Instruments" session from WWDC2023 goes into detail about how to use Instruments to analyze hangs, including how to identify whether the hang may be caused by SwiftUI-related work. A hitch is a user-perceivable animation issue, such as a pause during scrolling or skipped frames of an animation. The root causes of hangs and hitches, especially in SwiftUI, are often related. For more information on hitches, including how the system render loop works, check out the "Explore UI animation hitches and the render loop" tech talk video. Both hangs and hitches in SwiftUI often originate from a slow update. These slow updates have a number of common causes. The first is expensive Dynamic Property instantiation, such as allocating and initializing a state object or initializing state. Another source is work done in body. Make sure to check for expensive string interpolation or operations like data filtering and other work inside of body. It's important that body itself is as cheap as possible. These are all inter-related. For example, a dynamic property could be computed from a view's body, making the view expensive to evaluate. Slow identification also frequently happens in a view's body. Let's start by looking at an example from the fetch app.

In this example, I've been working on the root view of the app, which has an object that I use to create the dog list. Following the code highlight on this slide, accessing model.dogs in the body lazily instantiates the object, which brings us to the initializer, which fetches the list of dogs. As the code comment says, this could take a long time. This is synchronous work.

One way to fix this is by using the task modifier. We'll first make the fetching async. I'm only showing the addition of the async keyword here. Next, in the task modifier, we'll asynchronously fetch the dog list by awaiting it. That way, the app is responsive when the expensive data loading operation occurs. There are other sources of work that you might not realize are affecting your app. For example, string interpolation can often be expensive, so make sure to cache any strings you might need to frequently use. Similarly, looking up values from bundles can be expensive. And of course, any heap allocation, such as for a class-bound type, can add up. Let's move on to lists and tables. List and Table support rich features beyond a simple layout, adding selection, swipe actions, reordering support, and more. These are complex, advanced controls, and understanding identity is critical to ensuring they perform well in your app. In this section, I'll discuss identity in list and table and demystify how to maximize update performance for these built-in components. Before we dive into this subject, I'd like to touch on some improvements. In macOS Sonoma and iOS 17, SwiftUI has a number of optimizations under the hood for cases like filtering and scrolling. These improvements can be had with minimal effort on your part, and in many cases, can result in drastically more responsive load and update times for bigger lists and tables. However, there are certain ways to construct lists and tables that result in better performance. List and Table use identifiers to know what changes occurred to the data. For consistency, all the IDs of List and Table are gathered eagerly. Therefore, being able to quickly generate identifiers for your list and table contents directly translates to faster load and update times. Identity helps SwiftUI manage view lifetime, which is crucial for incremental updates to your hierarchy. A change to the identity means the view changed. This is important for animations and performance. For more information on animations, check out the "Fundamentals of SwiftUI Animations" session. Identification performance is important because identifiers are gathered often, especially for lists and tables. Let's walk through the list identification model.

I've been hard at work on the list of dogs in the app. I've started with just a single row. Here's the code for the list, with a single DogCell inside. The next step is to use ForEach to iterate over all the dogs. This example is simple, but it's directly related to identity, and adding a ForEach in a List is an important time to evaluate performance. To understand why, let's look at the generic signature of ForEach next. This is the signature for ForEach from SwiftUI. ForEach maps a collection of data onto a resulting sequence of views, producing explicit identity for each of its views. When you use List, it needs to figure out how many rows to display, as well as what the identifier for each row is. Therefore, it visits the data collection up front, determining each element's ID. The content closure is called to produce each view.

Rows are created on-demand. List uses a composite of the identity and the content to produce a list row.

The rows created on-demand correlate to the visible region, plus some system-determined buffer for prefetching or accessibility. As the view is scrolled, more views become extant. Here's the code snippet producing this ForEach. Note here that the content is just DogCell, which is itself single view, because it uses an HStack inside. ForEach is critical in determining the ultimate row ID used by the List. And List needs to know all of its IDs up front. But it can only do this efficiently without visiting all the content if the content resolves to a constant number of rows. As an example, let's say we want to refactor our list to only show those dogs that like to fetch a ball. It might be tempting to add a filter using a conditional view, like this. Here, the number of views is variable. It's either one or zero. This is bad because it results in list needing to build all the views to retrieve the row identifiers because it doesn't know how many views each element resolves to. The same is true if you use AnyView. Here, the number of views is now completely unknown. So we have the same problem as before: All rows must be created. What if we move the filter into the data collection itself? Now we're back to a constant number of views per element, and only those that are needed have their row contents constructed, but be careful: The inline filter here is linear over the collection. This might work in a prototype, but when the collection scales, this operation can quickly become expensive, leading to a slow update. It's better to move it out to the model. Now we have the best of both worlds: The filter is cached, so it won't run every time this list is constructed, and the number of views per element is constant.

Here are a few tips for how to ensure your view counts are constant. Note that this approach to view counts is only relevant in the context of ForEach within List and Table because those components gather their identifiers up front. As I just mentioned, avoid using AnyView and lopsided conditions. You can also use an explicit stack where appropriate, but note that certain modifiers like listRowBackground need to go after the stack and not within it. Finally, try to flatten nested ForEach constructions if you can. However, there is one place where nested ForEach can be valuable, sectioned lists. Let's take a look at an example.

In this example, I have a list of dogs that's sectioned by the favorite toy of each dog. I'm using ForEach to create a dynamic number of sections. and each section has a dynamic number of rows within it by nesting a ForEach. List will need to retrieve all of the identifiers, but because we're using sections here, SwiftUI understands this construction and ensures the list is still fast to render. Dynamic sections are a good example of when using nested ForEach is recommended. The basic equation to think about is that the row count resulting from a ForEach in a List is equal to the number of elements multiplied by the number of views produced for each element. You need to ensure the number of views per element is a constant, or SwiftUI has to build the views in addition to the identifiers in order to identify the rows. So far we've talked about List, but these rules generally apply to Table too. Table uses TableRow instead of views, and TableRow always resolves to a single row. Let's look at a Table example. Here I have the dog table, which has a ForEach inside. Because TableRow is always a single row, the number of total rows here is just the number of elements in the dogs collection. This construction is so common that, new in iOS 17 and macOS Sonoma, SwiftUI provides a streamlined initializer that lets you simply write ForEach of your data collection and creates the table rows on your behalf. While this initializer is new, it back deploys to all previous operating system versions where Table is available. Not only is this construction simpler, it also enforces a constant number of rows for the ForEach content, which helps with identification performance. However, there is a semantic change I'd like to call out that's new. If you have code like this, it could behave differently in the newest OS versions. In this example, we have a ForEach over dog, which also creates a row of dog. However, the dogs here don't match. The values are the dog's best friend. In iOS 16, each row became identified by its value. In iOS 17, this behavior has changed to improve performance. The reason is, now we don't need to identify each table row by looking into the ForEach. So this example now has the IDs of each of the dogs, instead of the TableRow's value. If you need to back deploy, you can get the old behavior by either mapping over your collection or by explicitly specifying an ID key path.

The basic equation to think about is that the row count resulting from a ForEach in a List is equal to the number of elements multiplied by the number of views produced for each element. In Table, this is similar, but it's the number of TableRows per element. We've covered a few tips and tricks for faster lists and tables here, namely that you should ensure identifiers are cheap to create and that the number of views in ForEach content is constant. We've covered a lot today. We started with exploring the graph to understand dependencies and optimize them. Then, we looked at slow updates and how to improve responsiveness. And finally, we discussed the importance of identity with Lists and Tables. With the right mental models, you can easily have great performance from the beginning of the development process, which lets you focus more on the details of your app. Thanks for watching. ♪ ♪

-

-

3:59 - DogView

struct DogView: View { @Environment(\.isPlayTime) private var isPlayTime var dog: Dog var body: some View { Text(dog.name) .font(nameFont) Text(dog.breed) .font(breedFont) .foregroundStyle(.secondary) ScalableDogImage(dog) DogDetailView(dog) LetsPlayButton() .disabled(dog.isTired) } } } -

4:00 - ScalableDogImage

struct ScalableDogImage: View { @State private var scaleToFill = false var dog: Dog var body: some View { dog.image .resizable() .aspectRatio( contentMode: scaleToFill ? .fill : .fit) .frame(maxHeight: scaleToFill ? 500 : nil) .padding(.vertical, 16) .onTapGesture { withAnimation { scaleToFill.toggle() } } } } -

4:01 - printChanges

expression Self._printChanges() -

4:02 - ScalableDogImage + printChanges

struct ScalableDogImage: View { @State private var scaleToFill = false var dog: Dog var body: some View { let _ = Self._printChanges() dog.image .resizable() .aspectRatio( contentMode: scaleToFill ? .fill : .fit) .frame(maxHeight: scaleToFill ? 500 : nil) .padding(.vertical, 16) .onTapGesture { withAnimation { scaleToFill.toggle() } } } } -

8:46 - ScaleableDogImage

struct ScalableDogImage: View { @State private var scaleToFill = false var dog: Dog var body: some View { dog.image .resizable() .aspectRatio( contentMode: scaleToFill ? .fill : .fit) .frame(maxHeight: scaleToFill ? 500 : nil) .padding(.vertical, 16) .onTapGesture { withAnimation { scaleToFill.toggle() } } } } -

8:47 - Updated DogView

struct DogView: View { @Environment(\.isPlayTime) private var isPlayTime var dog: Dog var body: some View { Text(dog.name) .font(nameFont) Text(dog.breed) .font(breedFont) .foregroundStyle(.secondary) ScalableDogImage(dog) DogDetailView(dog) LetsPlayButton() .disabled(dog.isTired) } } } -

8:48 - Final DogView

struct DogView: View { @Environment(\.isPlayTime) private var isPlayTime var dog: Dog var body: some View { DogHeader(name: dog.name, breed: dog.breed) ScalableDogImage(dog.image) DogDetailView(dog) LetsPlayButton() .disabled(dog.isTired) } } } -

12:22 - DogRootView and FetchModel

struct DogRootView: View { @State private var model = FetchModel() var body: some View { DogList(model.dogs) } } @Observable class FetchModel { var dogs: [Dog] init() { fetchDogs() } func fetchDogs() { // Takes a long time } } -

12:23 - Updated DogRootView and FetchModel

struct DogRootView: View { @State private var model = FetchModel() var body: some View { DogList(model.dogs) .task { await model.fetchDogs() } } } @Observable class FetchModel { var dogs: [Dog] init() {} func fetchDogs() async { // Takes a long time } } -

15:12 - List

List { ForEach(dogs) { DogCell(dog: $0) } } -

16:08 - List Again

List { ForEach(dogs) { DogCell(dog: $0) } } -

17:35 - List Fixed

List { ForEach(tennisBallDogs) { dog in DogCell(dog) } } -

18:25 - Sectioned List

// Sectioned example struct DogsByToy: View { var model: DogModel var body: some View { List { ForEach(model.dogToys) { toy in Section(toy.name) { ForEach(model.dogs(toy: toy)) { dog in DogCell(dog) } } } } } } -

19:21 - DogTable

struct DogTable: View { var dogs: [Dog] var body: some View { Table(of: Dog.self) { // Columns } rows: { ForEach(dogs) { dog in TableRow(dog) } } } } -

19:22 - DogTable Brief

struct DogTable: View { var dogs: [Dog] var body: some View { Table(of: Dog.self) { // Columns } rows: { ForEach(dogs) } } } -

20:06 - DogTable Different IDs

struct DogTable: View { var dogs: [Dog] var body: some View { Table(of: Dog.self) { // Columns } rows: { ForEach(dogs) { dog in TableRow(dog.bestFriend) } } } }

-