-

Making Apps with Core Data

Core Data helps manage the flow of data throughout your app. Hear about new features in Core Data that make your code simpler and more powerful, including derived attributes, history tracking, change notifications and batch operations. Learn more about using these facilities and the new diffing APIs in UIKit and Foundation to make your apps run more efficiently.

Resources

Related Videos

WWDC20

WWDC19

-

Search this video…

Hello, everyone. Welcome to making apps with Core Data. I'm Scott Perry. I work on the Core Data team. And today, we're going to have an accelerated refresher with a focus on best practices. We'll talk about how to get up and running with Core Data, how to set up an app's controllers for success. And as well as how to use multiple coordinators and scaling involving that. Then we'll wrap up with some useful testing tips.

So let's get started. This year, we released a new sample app. You may have already seen it in Session 202. It starts out with a list of posts.

We can add a new post by tapping on the Plus button at the top. And have a closer look in DetailViewController. So you can here -- see here that this is like a blogging app. It's supposed to support a title, content, multiple tags, as well as multiple media attachments where you can see the thumbnails down here.

Let's change the title and then also add a tag.

Hello.

Great. We'll save that and head back to the ListView.

Now let's look at the TagManager. You can see here that we only have one tag, called Demo, and it has three posts. So let's add two more, one named Cats. And another one named Dogs. All right, we'll dismiss this and then go back into our little toolbar here and add 1000 randomly-generated posts.

Here we go.

And if we go back to our tag list, we can see Dogs are more popular than Cats. It's science.

So now that we've seen our app, let's think about the shape of its data.

The most obvious type is posts. So we'll start with that.

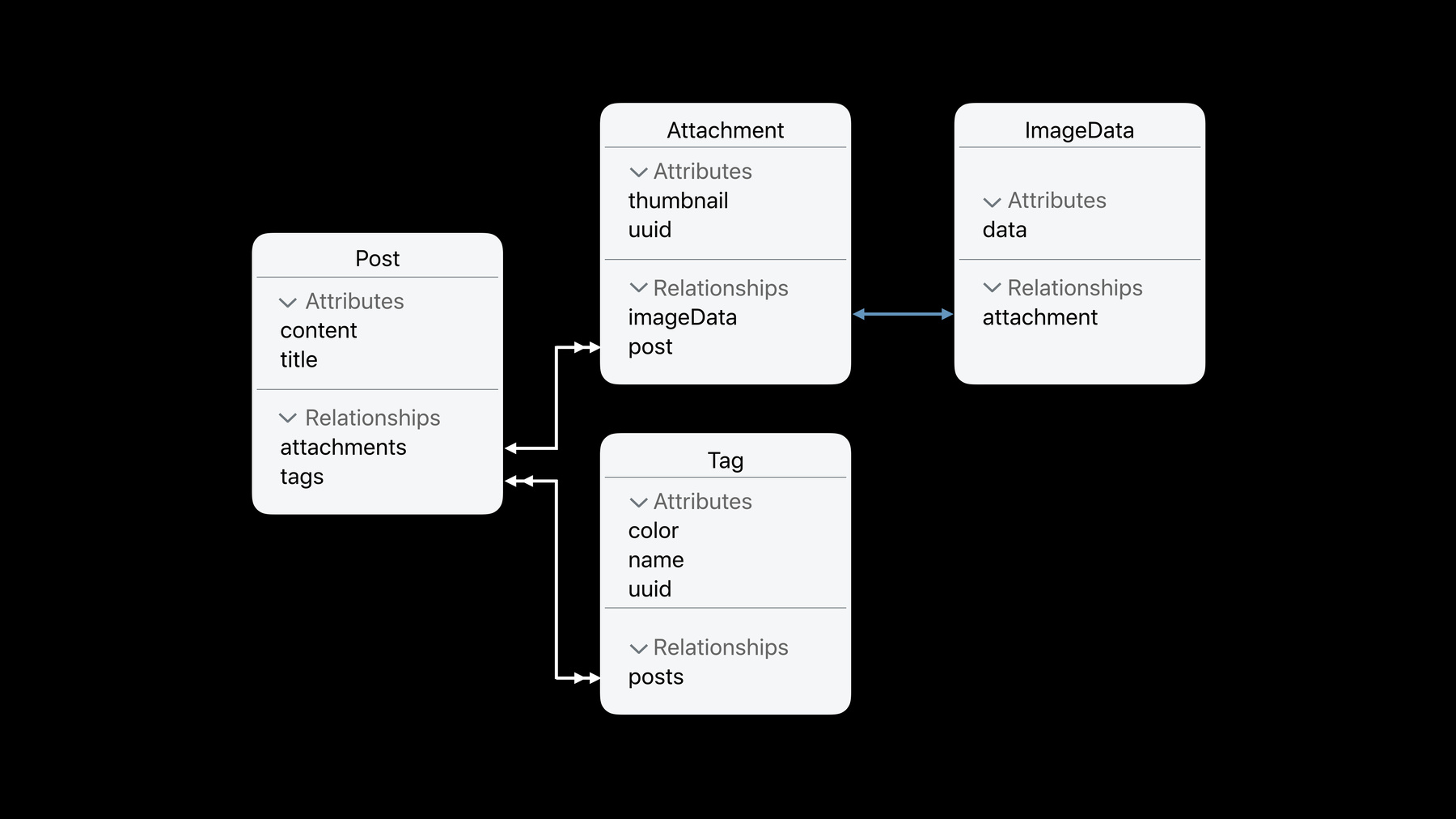

But since we support multiple media attachments, that's another type. And then we'll also need a tag type for the same reason.

But since attachments might be quite large, we'll want to store that data separately. After all, the list view only needs to show thumbnails, so we can keep the larger data elsewhere.

Now that we've organized the shape of our data, it's a pretty straightforward process to transliterate it into a Core Data model using the Model Editor and Xcode.

Here, we define the members of our modeled types, as well as the relationships between them.

For example, the relationship between attachments and their data is one-to-one. That is, an attachment can only be backed by one image data, and an image data can only represent one attachment.

We can also tell our Core Data in the model that if the attachment is deleted, then its image data should be cleaned up automatically. This is called a cascade deletion rule.

Meanwhile, the double arrow heads signify a too-many relationship. Here, a post may have many attachments, but an attachment will only ever belong to one post.

And finally, the post may have many tags. Tags may be on many posts. This is a many-too-many relationship.

So now, we've defined a managed object model. But there are a few more Core Data types that we need to get familiar with before we're ready to build our app.

The model is required by a PersistentStoreCoordinator, which as the name implies, is responsible for managing our persistent stores.

Most of the time, this is a database that lives on the file system, though it's possible to have many stores at once, including our own custom made types that derive from NSPersistentStore. Finally, the type that we'll spend the most time with is the ManagedObjectContext.

Core Data uses the command pattern, which is really a fancy way of saying that you need a context to get anything done. If you want to execute a fetch request, you need a context. Dirty-to-managed object, the context knows about it, and will save it on your command. Contexts needs to know a coordinator in order to do their work. And as I mentioned earlier, the coordinator has to know about the model to make sense of stores. The types are all sufficiently interdependent. But coordinator provides one type that encapsulates them all and represents the entire stack, called a persistent container.

Using a persistent container, we can set up a stack in just a few lines of code, especially if the model lives in our bundle.

All we need to do is refer to it by name, and the persistent container will load it for us.

If the model is generated in code, or we need to use the same model with multiple containers, there's another initializer that gives us the control we need.

Once we have a container, we tell it to load our persistent stores. The completion block gets called once per store with a nil error parameter on success, after which is time to shift our focus to managed object contexts. Contexts provide us with seamless access to managed data, and they have a few options that can make them even more useful to certain use cases, such as driving our views.

The first of these is support for query generations. Query generations provide a stable view of the stores data, allowing safe and consistent access to objects, even if they're changed or deleted by another actor.

To enable this, set the context's query generation to current. Current is a floating meta version. The context's query generation will get pinned to a concrete point in time on the next access to the store. Now the context has a stable view of the data in the store. What about keeping it up-to-date with the latest changes? Well, in the Stone Ages, we would register for context and save notifications. But contexts can also be configured to keep themselves up-to-date as changes are saved by their siblings.

Just that automatically emerges changes from parent to true.

Okay, so now all of our stack types are configured to our liking, how do we use them in our app? The most important thing to remember when using a context is that all store requests and interactions with managed objects must be done in the context queue.

Background contexts each have their own queue. So using them requires the perform API's.

There's a blocking invariant, as well as an asynchronous version. But for truly asynchronous work, the container offers a convenience method for performing background tasks that creates a background context for you, and disposes of it automatically when your block returns.

So now, how do we add data to our app? Well, if we only need a couple of objects, it's easy to use the initializer provided by the managed object sub classes that were generated for us from our model by Xcode. If the subclass is only used by one model, then it already knows which entity it represents. So we can use in it with context. Once it's been registered with the context, then we can configure it, treating it like any other instance variable.

Once it's set up to our liking, we call the contextSave method to persist it to storage.

But what if we need more data? Most apps aren't content with inserting a handful of objects at a time. Chances are good, you've got a server component that sends objects back by the hundreds or thousands. We can save these to the store one at a time, like we were just doing for a couple objects. But it's a lot of boilerplate to write, not to mention a lot of resource overhead, to have all of those in-memory at once.

Enter batch insertions, the first of many new features we'll be talking about today.

This code fragment is worth 1000 objects. And it all starts with your de-serialized payload in the form of an array of dictionaries that have string keys.

These keys need to line up with the names of your attributes in the model. It's okay to leave some out if they're not required by something like a unique constraint. If you've configured default values in your model, then Core Data will use those.

In this case, we have three dictionaries that each cover a different set of content and title attributes.

Going back to our code, we create a batch insert request with our array of dictionaries, as well as the objects model entity, which is also available through a method on the managed object subclass that was generated for us by Xcode.

Then we execute the request, and the context returns a response, which wraps a Boolean, that tells us if the operation succeeded.

We're getting a lot for free here. And I know you're thinking. What's the catch? Well, there's not really many sharp edges here. And a lot of this is going to sound familiar if you've used batch updates or batch deletions. If you have unique constraints than any existing objects matching the dictionary will be pulled out of the database and updated with new values instead. Attributes that are optional or configured with default values can be omitted from the dictionary as well. In the case of updating an object with unique constraint, the existing values will not be changed.

This goes for relationships as well. Batch insertions can't be used to set relationships. But if a batch insert updates an existing object due to a unique constraint, the existing relationships will be left alone.

And finally, like the other batch operations, batch insertions do not generate a contextDidSaveNotification, so you'll have to manage that on your own. Now that we have some data, let's talk about how to satisfy the needs of our controllers. The first thing that a controller needs to be able to do, is fetch and present data. So let's look at that.

We use a fetch request to get objects out of the store. And just like getting the entity when we created new objects, there's a method on the managed object subclass type generated by Xcode, that will give us a preconfigured fetch request.

Adding a predicate to the request allows us to refine our results, in this case, so we can fetch a tag by its name.

Once we've executed the request, you pluck the results out and use it to configure our views.

This works well for immutable data. But what if the tag's name or color changes while our view is up? Our managed object context will make sure that the objects' properties get updated. But we haven't done any of the plumbing here necessary to observe those changes.

As many of you know, managed objects have supported key value observations since the dawn of time. But the combined framework, announced this week, makes KVO much easier to use in Swift. We get a publisher out of the object for each property we want to wire up, and sync the data flow into an assignment subscriber on the view. In the case of the tag's color, we have an extra map step in the middle to make the types lineup.

This is all the code we need to write. And our ViewsContents will automatically get updated now whenever the underlying object changes. Yeah, Combine is great. And this is barely scratching the surface of the framework. It provides a lot more, very powerful, data flow functionality. And to learn more, I encourage you to check out Session 721. Now there is a deceit you may have noticed to this evolution of our code, and it's that DetailViews almost never actually have to fetch the object that they're presenting. Usually this kind of view is pushed from a parent that configures it with a managed object. So normally, the code we'd write would actually look like this.

The Parent to our DetailView is usually some kind of list view, like a Collection or a TableView. It also gets its objects from a fetch request. But there are a few more properties that we haven't talked about that are important when fetching a bunch of objects.

The first is the requestSortDescriptors.

These define the order of the results. In this case, we're sorting our tags by name. But if names weren't unique enough, we'd want to add another descriptor to the end of the array to break any ties.

Another useful option is batching. If our fetch request is going to match 14 million objects, we don't want them to all get loaded into memory at the same time. Even if we had the memory for that, which we probably don't, it would take a long time. Instead, we configure a fetch batch size to tell the context how many objects should be loaded from the store at a time. This makes a big difference on our app's responsiveness. But it only works when interacting with the result as an MS Array. Swift's array bridging defeats this optimization.

So with this knowledge, it's pretty easy to set up a fetch request that will fetch all the tags that we want to see. But what if one gets changed? Just like with the properties of an object that we're displaying in a detailed view, we need some way to keep up with the objects as the career changes.

Luckily, Core Data supports live queries in the form of a Fetch Results Controller.

Here we've configured a request to fetch all posts ordered by title, 50 at a time.

This fetch request is joined by a context to configure a type we haven't talked about yet called a fetchedResults Controller. It communicates changes to the fetch requests through a delegate protocaller and starts working as soon as you tell it to perform the fetch.

Now the Fetch Results Controller is probably well known to many of you already. The delegate protocols change reporting callbacks include a method to tell you when changes are going to begin coming in. Another to tell you when a section changed in some way.

And another tell you for each object that changed, how it changed. And finally, a method to tell you that we're done. And you know everything.

These methods were originally designed to line up closely with UITableView's API, but there was still a fair amount of glue code to write matching the career query results to the table redrawing. Furthermore, newer collection views don't support this change callback pattern.

So I'm very happy to announce that the Fetch Results Controller has learned some new tricks this year.

The first is a delegate method that vends an instance of NSDiffableData SourceSnapshot. It sounds like a lot of you already know what this type is. But in case you don't, it's a new type in UIKit MapKit that represents the structure of a collection or TableView. To use one, you configure your TableView's data source to be one of the DiffableDataSource, also new this year, and feed it snapshots. You can learn more about these types in Session 220. But for all our purposes, all you need to know is that you can use them to keep your collection views up-to-date in a single line of code. And that code fits in the remainder of the slide. This used to be a lot of boilerplate. All we're doing here is feeding the Snapshot to the DiffableDataSource. The data source diffs the snapshot against the previous view state that it has, which is what makes it a DiffableDataSource, and then uses it -- uses the computer difference to update the view. This has been a long time coming. The DiffableDataSource Snapshot works great for wholesale control of the collection view. But if you're looking for something that allows more customization, or you're managing the state of types other than Table and Collection views, we have another delegate method you may be interested in. Like with Snapshots, this method also gives you a summary of all the changes to the Fetched Results in one shot. But it uses a different type, also new this year, called CollectionDifference. Like the name implies, a CollectionDifference encodes the difference between, and can be generated from, two collections.

Collection diffing in the Swift standard library was introduced in Swift Evolution Proposal 240. But it also exists in Foundation. And you can learn more about that in Session 711.

For our purposes, it's a one-dimensional type. So it's only supported when you're not using section fetching. And like the SnapshotDelegate method, it's mutually exclusive with the legacy change reporting methods. So if you want to drive multiple things from a Fetched Results Controller, you should use multiple Fetched Results controllers.

So let's take a quick look at how we can drive a single section of a collection view using these differences.

Here's our Delegate method. And at the very top, we start by kicking off a batch update, and looping over the changes in the diff.

CollectionDifferences support two kinds of changes, Insert and Remove. And two changes of opposing types may refer to each other through association. So in the first case, we have an insertion that has an associated removal. This means the object has moved, or at least changed. It may not have actually moved logical position. But it doesn't matter, because the CollectionView is smart enough to tell the difference. And as long as we give it the right original and destination IndexPaths, then it will do the right thing.

In the second case, we have an insert of an object that was not previously part of the Fetched Results. So we tell the CollectionView to add it.

Finally, we match all removes that weren't part of an associated move by filtering for new associations, and then remove those from the CollectionView. And that's it. And you'll notice that this code composes well. So it's a good candidate for factoring into a function to further reduce your boilerplate, because all the state you need is the CollectionView and the difference. So we think people are really going to love these new delegate methods. But the old ones find new life this year as well. The Swift UI framework introduces first-party support for declarative interfaces, but it can't be driven with Snapshots or diffs. But this model type can be derived from our list of Fetched Results. Conveniently, the existing controller, didChangeContentDelegateMethod will tell us every time an updated set of Fetched Results is ready to update our views.

So it's easy now to apply Fetched Results to our views. But what if the results themselves were difficult to fetch? What if we wind up being unable to build a fetch request to fetch our data? Or what if we wind up with performance problems when we execute our fetch requests? At a certain point, the needs of the controller outweigh the needs of the model, and we have to give up some modeling purity in order to accomplish our goals. We do this with denormalization.

We talked a bit about denormalization during WWDC 2018 in Session 224. But to recap, denormalization is when we keep copies of our data, so access can be more efficient.

This comes with the price of some additional overhead maintaining that extra data. But there are a lot of circumstances where this tradeoff is a no-brainer.

Databases indexes are a good example of this. In exchange for maintaining a copy of all of our indexed columns, were rewarded with lightning-fast queries when they depend on those columns.

Looking back at our app, denormalization is also a useful way for us to keep track how many posts are using each tag. All we need to do is add an integer attribute to the tag type named postCount.

Now all we have to do is make sure that this new postCount attribute gets incremented every time a post is tagged and decremented every time a tag is removed from a post. Surely, this code will be bug free, and our data consistent forever, right? Right? No, enter derived attributes.

Derived attributes are normalized metadata that's maintained for you by Core Data. And it's not just for counts. There's a bunch of supported functions that you can find in the documentation.

Derived attributes are defined in the managed object model. The Model Editor in Xcode has a new interface for this. Or you can define derived attributes in code using the new type, NSDerivedAttributeDescription.

And finally, derivation expressions can refer to any of the properties of an entity, one level deep.

Derived attributes make denormalization super easy. And I'd love to take a moment now to show you how to adopt them.

Here we have our app, just as before. And if we look in our Tag Manager here, we can see that we have three tags and a whole bunch of posts. But the view code that's driving this here is actually traversing the relationship posts and getting its count, which faults in the relationship when we do it. So if we had many orders of magnitude more data, this could wind up being a performance problem for us. So let's fix that by using derived attributes in our model.

Here's our model editor. And we're looking at the tag type right now. So we're going to go in here and add a new attribute called postCount. And we're going to make that an integer type.

Now if we go over to the inspector here, we can see a new checkbox that says derived. And if we click it, we wind up with a space for a derivation expression. So here, we're basically moving our code from the view into here. Let's say posts. @counts, since we're using an aggregate function.

And then that's it. If we rebuild, Xcode will rebuild our managed object sub classes. And when we go back to the view, here, we will find a new instance variable called postCount, but it's not optional. So we get to delete even more code by getting rid of this conditional. If we build and run, we should see that nothing changed. Except it's way faster and better. And we don't have to keep anything up-to-date. And sure enough, there it is. The complete set of supported derivations is available in the developer docs. But generally speaking, they come in four classes. The simplest is outright duplication, like keeping a copy of an attachments identifier and the image data that backs it.

The other kind of derivation is a simple transformation of the fields, such as lower casing a tag's name, or canonicalizing some Unicode string.

We just saw an example of an aggregate function across a too many relationship in the demo.

And lastly, there are global functions such as now that take no parameters at all, which are useful for things like keeping track of when an object was last updated. So now that our controller is want for nothing, it's time to talk about some more advanced topics and scaling. PersistentHistory was introduced in 2017 as a tool to help you do things like process data added by an importer, or maintain data consistency across multiple active coordinators that are using the same store.

New this year, we've recruited fetch requests to make it easier to look up only the history you're interested in.

Maybe you want to look up the changes made by an extension, or only changes that affect posts, or only history within a certain range of time. I think what is the power of the fetch request applied to your PersistentHistory.

Now and NSPersistentHistoryTransaction and NSPersistentHistoryChange are not modeled types, but they've both sprouted some new cross-methods to make them work with fetch requests. If you squint, the new methods look similar to what you would find generated by Xcode for your managed object subclass types.

They include accessories for an entity description corresponding to the type, as well as a method that produces a new preconfigured fetch requests that will return instances of the type, either NSPersistentHistoryTransaction or NSPersistentHistoryChange when executed.

You configure the fetch request to the predicate, just like your fetching managed objects. But instead of executing the fetch requests directly against the context, the fetch request gets used as part of a PersistentHistoryRequest.

There's a new convenience initializer on NSPersistentHistory ChangeRequest for creating a new instance with a fetch request, as well as immutable property you can use for post-talk configuration.

Harnessing fetch requests for PersistentHistory provides a lot of granularity to our application. But there's still the question of how do we know when history gets made? There are a lot of ways we could do this, but they all have drawbacks. We could pull the store for changes every so often. But it's hard to tune that kind of solution for the right compromise between wasted effort and delays before changes are noticed. File System monitoring systems like Dispatch Sources, or FSEvents, are useful, but they only work with file back stores, they're not trivial to adopt. And it's likely that you'll get a lot of notifications that don't actually correspond to changes being committed to the store. So there's still a lot of wasted effort there.

While useful as Band-Aids, these approaches are all imperfect solutions to the problem of knowing when other coordinators change the store.

This year, we're introducing a new kind of notification. You can think of it as a cross-coordinator save notification, but the events are delivered asynchronously. So the really like cross-coordinator change notifications, we call them remote change notifications.

To turn on remote change notifications, there's a new PersistentStore option called NSPersistentStore RemoteChangeNotification PostOptionKey.

Set it in your store description before loading the PersistentStore into the coordinator, and the coordinator will listen for remote changes to the store.

This option also tells the coordinator that it should send remote change notifications whenever it makes any changes. So if you want change notifications, you want to use NSPersistentStore RemoteChange NotificationPostOptionKey on all of your coordinators, not just the ones that want to consume changes. You also probably want to be turning on PersistentHistory, because sure. Remote change notifications can tell you which store changed with the NSPersistentStore URL key in the notification's user info dictionary. But if you have PersistentHistory enabled, it also includes the new history token created by that transaction. This is especially useful when combined with the new PersistentHistory fetching features that we were just talking about a second ago.

Because remote change notifications work kind of like push notifications, sometimes changes make it collapse together if there are many at once. And only the last would get delivered. If we free launch our app, how do we know what the current PersistentHistory token is? Well, we can get it with a new method on the persistent store coordinator for -- called CurrentPersistent HistoryToken. All of these new pieces together can be used to solve puzzles that weren't possible before. Not only can we keep up a state in a timely manner, but PersistentHistory can also be pared down to only the changes that affect our work. Now I think the best way to show that to you is with another demo. So let's see what that looks like in our app.

So here, we have a controller that has the responsibility of keeping the view context up-to-date whenever a coordinator changes. So we've already registered this method, storeRemoteChange, to be called whenever we get a remote change notification.

Once we're in it, we can pull out the new PersistentHistory token that was saved out of the user info dictionary. And we'll grab the context that we want to update and hop into perform block.

The first thing we want to do to reduce the PersistentHistory to only what we're interested in, is to build predicates based on the last history token we saw, which in the case of what our app just launched, was the current PersistentHistory token.

And get all transactions before or equal to the new history token that we just got in the notification.

If we're using transaction authors, and we should, then we can also create a predicate that allows us to look at only transactions that were created by other coordinators other than our own.

So then, we can build the history fetched requests to get transactions, and configure it with a predicate that's a compound and predicate of other predicates we just built. So now we're only going to get transactions authored by other coordinators between the last one we saw, and this new one that just got posted inclusive.

We create an NSPersistentHistory ChangeRequest, and you configure it with this fetched requests you've just built, and then execute it against the context. The result is a list of transactions that we're not up-to-date on. So for each of them, we can pull out the objectIDNotification userInfo dictionary, and then pass that into the ManagedObjectContextMethod mergeChanges fromRemoteContextSave, that we announced in 2017.

Once all the transactions have been processed, our view is now up-to-date with the latest on-disk data in the store.

And it's done in pretty close to real time since the push notifications locally are very fast.

Finally, just to make sure we don't do any unnecessary work next time, we remember the last PersistentHistory token that we processed.

And now, we're ready for another remote change notification.

Alright, and that is PersistentHistory fetching and remote change notifications. Ah, finally, I wanted to spend a bit of time talking about testing.

While hopefully everyone here is running their tests in multiple configurations with desanitizers as well as in release, I wanted to start some advice that focuses a bit more on Core Data.

Number one is to know what your performance goals are. A Contacts app should be testing with at least tens of thousands of objects. But with that kind of performance goal, a linear algorithm might actually be acceptable on desktop hardware some of the time. The Photos app, on the other hand, should have tested to validate everything works correctly when there are millions of objects. At that scale, anything slower than logarithmic time is enough to hang the app. And so it's really important to test like you fly by running all of your integration tests with the performance data set.

But the integration tests should also get running configurations optimized for detecting and surfacing other kinds of issues as well. For applications using Core Data, that should include taking advantage of the Framework's built-in concurrency debugging.

You can enable it by going into the Scheme Editor and setting com.apple.CoreData ConcurrencyDebugged1 in the process arguments list.

Running integration tests in multiple configurations can take a lot of time. And likewise, unit tests need to be as fast as possible. So it's good idea to use in-memory stores when test runtime is important.

In this case, I specifically mean the SqLightStores in-memory mode.

SqLightStore has long supported in-memory mode. To take advantage of it, in between creating a persistent container and loading its stores, we can pull out the store description and set its URL property to point to dev/null.

This creates an extremely performance stack. But this in-memory store can't be shared between coordinators. So to validate all that remote change notification work we just did, we want to take advantage of named in-memory stores instead.

A named in-memory store is defined by adding a path component after dev/null. And any other SqLightStore with that URL in the same process will connect to the shared in-memory database.

Different coordinators sharing the same in-memory store will also dispatch remote change notifications to each other, which allows us to test all of our logic.

Finally, use the sanitizers. Each of these has saved me at least once. I've seen the trust sanitizer instantly identify a one byte buffer overflow that would have taken months to isolate. Similarly, thread sanitizer understands critical sections and can tell you about threading races that are impossible to reproduce in-house. And finally, UBSan lets you fix bugs before they happen by identifying undefined behavior that may change in the future. So today we've seen how to get set up with Core Data, about how to take advantage of new and existing APIs to write compact, seamless, and robust integration between the model and controller layers. We've explored keeping things in sync between multiple coordinators, and we've characterized our needs and written tests around them, so we can ship with more confidence.

As always, we'd love to hear what you think, so please let us know using Feedback Assistant.

For more information, please check out the developer website. This session's page will include links to the other sessions mentioned here today.

We'll see you in the labs tomorrow. Thanks for coming. [ Applause ]

-