-

Build programmatic UI with Xcode Previews

Learn how you can use the #Preview macro on Xcode 15 to quickly iterate on your UI code written in SwiftUI, UIKit, or AppKit. Explore a collage of unique workflows for interacting with views right in the canvas, find out how to view multiple variations of UI simultaneously, and discover how you can travel through your widget's timeline in seconds to test the transitions between entries. We'll also show you how to add previews to libraries, provide sample assets, and preview your views in your physical devices to leverage their capabilities and existing data.

Chapters

- 1:26 - What are previews

- 3:42 - Preview syntax basics

- 4:44 - Writing SwiftUI previews

- 5:50 - Writing UIKit & AppKit previews

- 6:08 - Demo: Putting writing previews into action

- 11:39 - Writing previews for widgets

- 15:58 - Previewing in library targets

- 20:28 - Passing sample data into previews

- 22:08 - Previewing on devices for full fidelity and access to data

- 25:50 - Wrap-up

Resources

Related Videos

WWDC23

-

Search this video…

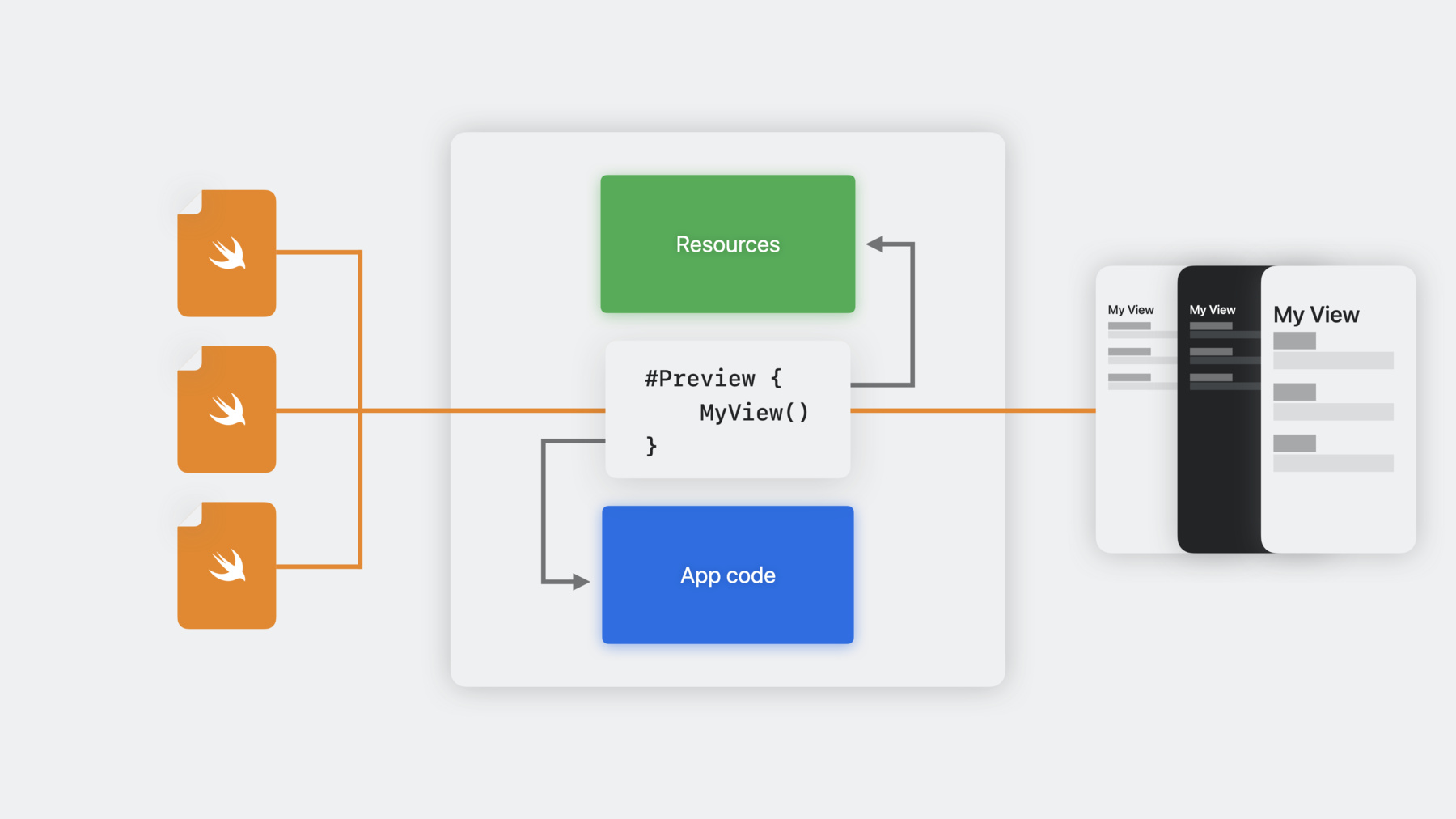

♪ ♪ Kevin Cathey: Hi, my name is Kevin, and I work on Previews. Building software, and especially apps, is a really iterative and creative process, so you want the fastest way to test your code and experience what you’re making come to life. That’s why we made previews; so you can have that near-instant visual feedback so you can focus on being creative. And previews are built to be flexible. You can use them across your entire app with different kinds of views, data, and devices. Whether you’re new to previews, or you’ve been using them for a while, I want to help you make the most of them. We’ll do this in three parts. First, we’ll review what previews are. It’s helpful to understand a little bit of how they work and how they relate to the rest of the code in your project. Second, there are two different ways you can provide content for your previews: views and widgets. I’ll show you how to write these and some of their unique workflows in Xcode. And finally, as you start to adopt previews in your project, there are some common scenarios or questions you’re bound to encounter. I want to give you a couple of tips and tricks to help take previews further in your project. Let’s get started. So what are previews? A preview is a snippet of code that makes and configures a view. They are written at the top level of a source file, meaning they are not nested inside of any types or functions. And they can literally be this simple. You use the #Preview macro, and return a view. Previews are compiled into your app, right alongside the rest of your app code and your resources. Because your previews can access these symbols and resources, previews are really flexible. You can do whatever you need to set up a preview for any view in your app and it will appear right in the canvas in Xcode. But previews are also about iterating faster. When you edit any of the Swift code in your project, Xcode will do two things automatically. First, it'll examine the change you made and recompile the minimal amount of code. And then, second, re-run your preview. This means that you can focus on writing and iterating on your code, and Xcode will automatically handle building, running, and updating your previews. And, once you have a preview defined, Xcode can run that preview in different contexts automatically without you needing to write any additional code. For example, you can test it in dark mode or different type sizes and orientations. This isn’t a perfect analogy, but it might be helpful to think of previews similar to tests. Like tests, previews run real code in your real project. We're not emulating or interpreting code. This means you have confidence that what you’re testing and previewing represents what the people who will use your app will experience, too. Secondly, investing in writing tests and previews, they ultimately help you develop faster. Even a little bit can go a long way. Third, you can test and preview different layers of your app. For example, with tests, you can have high level UI tests that exercise a significant portion of your app’s functionality, and you can have smaller unit tests that test individual components. Similarly, you can have previews for views that encompass a lot of your application, and you can have previews that show individual leaf views. That’s a quick look at how previews work. Next, let’s focus on how you write them and the kinds of content you can preview. Regardless of what you preview, every preview you define has the same basic shape with three pieces. First, start with the Preview macro initializer at the top level of a source file. Then, return one or more trailing closures of content. This is where you can configure your UI for exactly the scenario that you want to preview. And that’s all that’s required to make a preview, but you also optionally can configure the preview itself for even more flexibility. You can give it a name, and depending on the content of the preview, you might need or want to pass additional configuration in the initializer. We’ll look at some examples of this. Let’s talk about the kind of content you can preview. There are two main kinds: views and widgets. Views can come from SwiftUI, UIKit, or AppKit. For SwiftUI, just return any view that you’re working on. But you don’t have to just pass the view you’re working on; You can place it in whatever other views that you need. And this is helpful because oftentimes you want to work on a view in some broader context. For example, a view that’s always really intended to be in a List.

This is also the place to attach modifiers that provide data through the environment if the views you’re previewing need it. Previews are kind of like the scenes that you define at the top level of your app. Scenes serve as the entry points to your app. You set up data and you pass it through your views. Previews serve the same purpose, so you can use the preview to set up data and assets and then pass them into the views you’re previewing. When it comes to configuring the preview, you can give it a name. And view-based previews, like SwiftUI, support passing one or more configuration traits as a variadic argument list. For example, you can set a starting orientation for the device that you’re previewing on. The shape of the API is the same for UIKit and AppKit. Instead of a SwiftUI view, just make a view controller, and configure it as needed. Beyond view controllers, you can also preview a UIView or NSView directly. So there’s lots of flexibility depending on what you’re trying to build. I want to show you what we’ve talked about so far so that you can get a sense of how to start using previews and some of the tools that make previews so flexible. I’m in the middle of writing an app that makes collages of images. I can pick the photos, I can pick the layout, and add filters. Let's go to Xcode and explore the features of the Preview canvas. I’ve started writing the view that lets me add a filter to an image. To help me iterate on this view, I’ll need a preview. To start, I’ll make sure the canvas mode is enabled by going to upper right of the editor and clicking the options menu. The canvas mode is enabled by default for new projects, but if you have an existing project, you might need to turn this on. But even with the canvas mode enabled, the canvas stays hidden unless there is a preview defined in the file, so let’s add one. When I start typing #Preview, Xcode suggests a preview for me. Once I accept the completion, Xcode builds and runs my preview, and my view appears right in the canvas. There are three different modes I can use to work on my view. These appear in the bottom left corner of the canvas. The first and default mode is the live or interactive mode. I spend most of my time in this mode because I can interact with my view in the canvas like dragging these sliders.

I can also test animations and I can call and respond to asynchronous code. The second mode is the selection, or static mode.

This mode takes a snapshot of my view and allows me to interact with the elements in the canvas. Clicking a view highlights the line of code that made it in the source editor. And if I double click certain text views, like this Label, it will move the focus to the source editor so I can quickly change it. Vignette is a more succinct label. Let’s talk about the environment. That is, the preview environment. The canvas is showing me my preview in light mode, but what if I want to see it in dark mode? I could go edit my code to set the color scheme, but oftentimes I just want to quickly check it in dark mode and maybe make some tweaks. I’m going to use the Device Settings popover in the canvas instead. In the bottom bar, click the controls icon to bring up the settings. Now I can enable dark mode or a specific dynamic type size. But what if I want to see what my view looks like in both color schemes at the same time? Well, for this, I’ll use the third mode of previews: variants.

When I click the variants mode in the bottom of the canvas, I can pick which device setting I’d like to see all the values for, like color scheme, or all of the dynamic type sizes. I can inspect an individual variant by clicking it, and then I can page through each of the variants. Hmm. When I get to these larger dynamic type sizes, my view really starts to fall apart, doesn’t it? Let’s fix it. Instead of a VStack, I’m gonna use a Form, which is perfect for groups of controls. And forms look great when the controls are placed in Sections. Let’s make each HStack be a Section. I can make these changes across all of my HStack instances by taking advantage of multi-cursor editing. I’ll select the first HStack, then press Command-Option-E to find and insert a cursor for each instance of HStack. I’ll change each of these to Section.

I also want a header for each Section, which is provided in a second trailing closure. Arrow down and add the additional trailing closure.

Let’s use the Labels we already have for these headers. Arrow back up to the Labels and press Command-Option-Right Brace to move the Labels down into the header. And wow, our view looks a lot better. These same features all work great with AppKit and UIKit views and view controllers, too. I’ll switch tab to the view controller that renders a filter using CoreImage, and switch the canvas back to live mode. Now, I’ve already made a preview for this view controller, and it looks really similar to the SwiftUI one. In the preview macro, I created a view controller and I passed it a sample image. But I’d like to test this image with a filter applied, so I’ll add the code to pass a filter to my view controller. And, ah, bloom and vignetting. Never gets old. Besides configuring my view controller, I can also configure the preview. Any preview can have an optional name as the first argument. And with view previews, like SwiftUI and UIKit, I can add one or more traits in a variadic list after the name. For example, I can set the preview to start in landscape. That’s a quick tour of writing view previews.

The second main category of content you can preview is widgets. Widgets really highlight just how fast previews can be. There are two kinds of widgets you can preview. First, widgets that use a timeline provider which produce individual entries. In Xcode, you can preview either an entire timeline provider, or you can make your own timeline of entries right there in the preview. Let’s go to Xcode to see an example of each of these. My image collage app has a widget with a timeline provider that shows me a randomly built collage every hour. For my timeline provider, I’ll make a preview with three things: First, the widget I want to preview. Second, the timeline provider. And, third, the widget family to use for previewing.

That’s a small amount of code, but it gives me some great workflows in Xcode. Even though this widget will build a random collage every hour, I don’t need to wait an hour to see every entry in the timeline. Previews snapshots each timeline entry and shows them in the canvas. I can click through them, or use the arrow keys. And when I do, Xcode communicates with my widget and shows the transitions with animations between these entries, allowing me to spot any issues, not just in the user interface, but the changes between different points of the timeline. Like here, between entries 8 and 9. The animation here is not great. It just cross fades. I want to fix this scenario, but my timeline provider is random, so I don’t know if I’m gonna see this scenario again when I’m testing. This is where a timeline of specific entries comes in handy. I can craft the exact scenario I’d like to iterate on. I’ll change timelineProvider: in the Preview to just timeline, and then, instead of returning a timeline provider, I’ll return the two entries that replicate the case I want to fix. But the code I need to fix for this transition lives in another file, and I don’t want to lose this preview when I navigate away. Conveniently, I can keep the preview in the canvas by using pinning. If I click the pin button in the upper left of the canvas, it'll keep the preview active even when I navigate to another file.

Here’s the view that draws the collage and contains the transition. To help me focus on fixing the issue, in the canvas, I can press the play button in the timeline, and, the loop button. Now Xcode will keep replaying this transition while I fix the code. And, ah, here’s the problem. When the collage is composed of rows, I have a transition attached, but I don’t have one when the collage is composed of columns. I can copy and paste the transition. And that’s better, but it’s animating off the trailing edge. I think pushing off the bottom would be better. And there we go. With previews, I was able to iterate quickly, not just with my timeline provider, but I was able to fine tune animations using specific events. It really makes building and iterating on my UI faster and more fun.

These same widgets workflows are also available for the second kind of widget you can preview: live activities. The API looks nearly the same but instead of providing a timeline provider and entries, you provide a set of live activity attributes and a set of states. Here’s an example. First, pass in the attributes you want to use in the initializer. Then second, pass in content states for those attributes. For example, if you were building a widget for ordering pizza, you could provide a custom set of states for how the baking and the delivery of that pizza is going, and then test the animations between all of those states. I’m just scratching the surface of what you can do with previewing widgets.

Check out the session "Bring Widgets to Life" to learn more.

As we move into the final part of this talk, I want to help you make the most of writing previews in your project. We’re going to survey three different scenarios that affect setting up your project, providing data, and leveraging the capabilities of our devices. First, I want to talk about previewing content in library targets. This includes frameworks, Swift packages, or dynamic libraries.

There are many reasons you might be using libraries. For example, you might be using libraries to modularize your project, or you might be developing a library to distribute to others. Previews works great in these targets, but what’s neat is that you can leverage library targets to take previews further in any project. The first step in leveraging libraries is getting a sense of the executable that Previews uses for running your code. Previews need an executable, an app or a widget, to launch and render previews. Normally this is your app, but if you don’t have an app, how does this work? Previews uses three things to figure out which executable to use. One, the source files that you’re working in. Second, the targets containing those files and all the dependencies of those targets. Then third, previews intersects those target dependencies with the targets in the scheme that you have selected. Previews will only select an app that's in the active scheme. Let’s look at a few examples. In the simplest case, you might be working in a single source file that’s the member of an application target. It’s probably not a surprise that this is the app we’ll use for previews. But what if you have that source file in two targets? For example, a trial version of your app and the full version of your app. This is where the scheme comes in. Previews will only use the app that is in the active scheme. Here’s another example: Say you have two Swift files open, each belonging to a package that might also be imported by another package, which are then all imported by an app. We’ll traverse up from those files to find the first common executable at the top. With that in mind, now we can return to the question we started with: what if I don’t have an app at all? In this case, previews makes an app on your behalf, called the XCPreviewAgent, which will load your library. This all happens automatically for you, but it’s helpful to know how this works and especially the name of this process so that you can know where your code is running. For example, if there's a crash report for XCPreviewAgent, you can know it’s happening in your code and find where the problem is. But, you can take advantage of library targets to make previews work better in your project in at least two ways. We could spend a lot of time talking about each of these, but I want to at least mention them briefly. First, if you modularize your app into libraries, you can create smaller schemes to get better build times or just to be able to focus on one part of your project. And even though you are using a smaller scheme with a subset of your targets, you can still get the full power of previews. Second, if you then modularize code into libraries, there might be views that need required entitlements or Info.plist keys that your app target was providing. You can still preview these views by creating a small app just for previewing. Here’s how.

Let’s say I’m making a view that uses the Photo library, which requires a specific Info.plist key, and I’ve put that view in a library-- for example, SamplePhotoLibraryUtilities.

I can preview with the right capabilities by making a new app target. Then, I’ll add whatever capabilities I need. In this case, I need to add an Info.plist key, so I’ll go to the build settings, filter for the Photo library usage string, and set it. Next, I’ll make sure my library with the view I’m working on is embedded into my app. Using the build phases tab, I’ll add it as a target dependency, and embed it with a copy files phase. Now I’m ready to select the scheme that contains just this preview app and my library. When I preview my view, it'll use the app I just made for previewing, and all of the right Info.plist keys will be in place.

This lets me take advantage of smaller schemes with faster build times while keeping the ability to preview all of the views I’m working on. Next, let’s talk about how to get data and assets into your previews. I already snuck this into a previous demo, but I want to go back and review what I did. Let’s return to the view controller we were looking at earlier which rendered a filter. When I configured the preview, I passed in a sample image. This image is coming from an asset catalog in my project. If I reveal the project navigator, the asset catalog is located here, inside of a previews Contents folder. These images are great during development to help me test different scenarios and not require configuring every device I test with photos. But I don’t want to ship these in my app. I can avoid that with a feature called Development Assets. These are folders in my project that I configure in my build settings, and anything in those folders is removed from my app when I submit to the App Store. This could include asset catalogs or any resources you use to help you preview. Let’s add this Preview Contents folder as a development asset path.

In the project settings, go to the build settings tab, and I can filter for the development assets. After double clicking to edit, I can manually type in a path or I can drag the Preview Content folder into the popover.

With that added, now this path will be removed from my app when I submit to the App Store. A development asset path is set up automatically when you make a new project or app target, but you can add additional paths or add them to other target types or existing projects.

That demo highlights how one way to provide assets for your previews by adding them to your project using development assets. This works great if you want to share all of these assets across all your devices and across your team. But there’s another way to provide data and images if you’re looking to get up and running quickly. Many of us already have assets and data on our devices. Previews lets you leverage those too. The simulators in Xcode can do so much and are a fantastic starting point for most development. Previews work great in the simulator, and they also work great on physical devices. There’s reasons why you’d want to preview on the device your app will ultimately ship on. For example, you want access to the camera or to sensors. Another reason is that your device probably already has a lot of real data on it, for example, photos or files. I’d like to show you an example of how to leverage your device’s data.

Another view that I’m in the middle of working on has a button that allows me to pick photos from my iCloud photo library and then pick a layout to make a new collage. I’d like to test that out in the same way I’ve iterated on my other views, but I need to use a device that has a great selection of photos. I’m going to change which device is used for previewing using the preview device picker in the bottom of the canvas. Let’s dive into some of the options.

Most of the time, you can stick with the Automatic mode, which will track the device family of the run destination you have selected. On the literal opposite side of the menu is the More submenu. This lists all of the simulator devices you’ve added in the Devices window, so you can pick exactly which model you want.

Sometimes, though, you just want to pick a device by its feature. The middle section of the menu offers devices by common features so you don’t have to remember exactly which model had Touch ID, for example.

But I want to use this device next to me, so I can access the large set of photos from my library.

The preview device picker also includes any devices connected to my Mac. When I pick one of these connected devices, Xcode will build and preview exclusively for this device, bypassing the simulator entirely. And just like that, I have my view running on a real device. But just because it’s on my device doesn’t mean I can’t use the features of previews we’ve talked about so far. I can still use all the modes of canvas and even set device settings. For example, what does this look like in Dark Mode? And updates to my code show up instantly on my device. This view needs a navigation title, so I’ll add the navigationTitle in code, and then, I'll customize the title and review it on the device immediately.

That is just so fast! Now I’m ready to test my Photos library integration using all the images on this phone. I’ll tap Add from Photos, select some photos-- Aww, this squirrel is cute-- and tap Add. This view is working great. My photos appear in the layout picker, and I can quickly test different layouts. I love this. Editing in Xcode and experiencing my views come to life on my phone never gets old. And that’s three tips and tricks for using previews in your project. A couple things to wrap up: the Preview API gives you the flexibility to define previews for UI across your entire application and for all of our platforms. You can use SwiftUI, UIKit, AppKit, and multiple kinds of widgets. Previews are also flexible in letting you configure your preview exactly how you need. You can pass in sample data and assets, set up the environment in code, and take advantage of features in Xcode for testing out different device settings. And previews also gives you the flexibility of previewing on different devices, whether it’s the convenience of the simulator right in the canvas, or by using a physical device to get the highest fidelity or to access data and photos. But you still get all of the features of previews regardless of what device you pick. Finally, if you modularize at least parts of your application into libraries, you can create schemes in Xcode to get better build times and to focus on the one thing you’re working on.

Previews are here to help you be creative. Thanks for watching.

-

-

1:30 - Basic preview

#Preview { MyView() } -

5:05 - Previewing a SwiftUI view in a list

#Preview { List { CollageView(layout: .twoByTwoGrid) } .environment(CollageLayoutStore.sample) } -

5:37 - Previews can have a name and configuration traits

#Preview(“2x2 Grid”, traits: .landscapeLeft) { List { CollageView(layout: .twoByTwoGrid) } .environment(CollageLayoutStore.sample) } -

5:58 - Previewing UIKit view controllers and views

#Preview { var controller = SavedCollagesController() controller.dataSource = CollagesDataStore.sample controller.layoutMode = .grid return controller } #Preview(“Filter View”) { var view = CollageFilterDisplayView() view.filter = .bloom(amount: 15.0) view.imageData = … return view } -

7:08 - Xcode can help suggest a preview

#Preview { FilterEditor() } -

11:30 - Setting a UIKit preview to start in landscape

#Preview("All Filters", traits: .landscapeLeft) { let viewController = FilterRenderingViewController() if let image = UIImage(named: "sample-001")?.cgImage { viewController.imageData = image } viewController.filter = Filter( bloomAmount: 1.0, vignetteAmount: 1.0, saturationAmount: 0.5 ) return viewController } -

12:20 - Previewing a small widget with a timeline provider

#Preview(as: .systemSmall) { FrameWidget() } timelineProvider: { RandomCollageProvider() } -

25:07 - Updating the navigation title while previewing on device

.navigationTitle(“Add Collage”)

-