-

Write tests to fail

Plan for failure: Design great tests to help you find and diagnose even the toughest bugs. Learn how to improve your automated tests with XCTest to find hidden issues in even the best code. We'll explain how to prepare your tests for failure to make triaging issues easier, letting you solve interface issues and deliver fixes quickly.

To get the most out of this session, you should already be familiar with writing UI tests within the XCTest framework.

For more on testing tools, head over to “The suite life of testing”.Resources

Related Videos

WWDC22

WWDC20

-

Search this video…

Hello and welcome to WWDC.

Hello and welcome to "Write Tests to Fail." My name is Kelly Keenan and in this session, I'll be sharing some of the lessons I've learned over the years of writing user interface and integration tests for Xcode.

While I'll focus on UI tests, many of these lessons are applicable to unit tests as well. Regardless of whether I wrote my tests before or after I wrote my code, my main motivation has always been to get our tests to green, because seeing this icon tells me that my tests are passing, which means I can ship my product. However, my new mantra for this year is write tests to fail, because great tests catch bugs, so we should plan for failure. Tests are written once, but are triaged many times. When my tests find a product bug, it fails, which is exactly what they're designed to do. In my case, my tests all run in a continuous integration system, so the tool I have for triaging the failure is the test result bundle. In this session, we'll explore ways I've found to make my tests easier to triage with just the result bundle as well as ways to make my tests more robust so that I'm spending time triaging the product failures instead of debugging my tests. The test templates follow the testing pattern of set up, test, and tear down.

Within the test section, we can break this down into actions and assertions. We'll use this as the agenda for this session. So, let's start with the set up for our tests.

This is where I explicitly state the assumptions I require and set the state of my app and environment before I run my tests.

In Xcode 11.4, we introduced a new setUp function called setUpWithError which now throws, allowing me to catch or pass on any errors that are thrown during my setup. I found it useful to modernize my existing setUp methods to take advantage of the error management. I use the setUpWithErrors method to set the initial state required for my tests before they run because previous tests may have changed the state of my app or modified data that my tests use.

In this example, I set continueAfterFailure to false so that my test fails immediately when an issue is found.

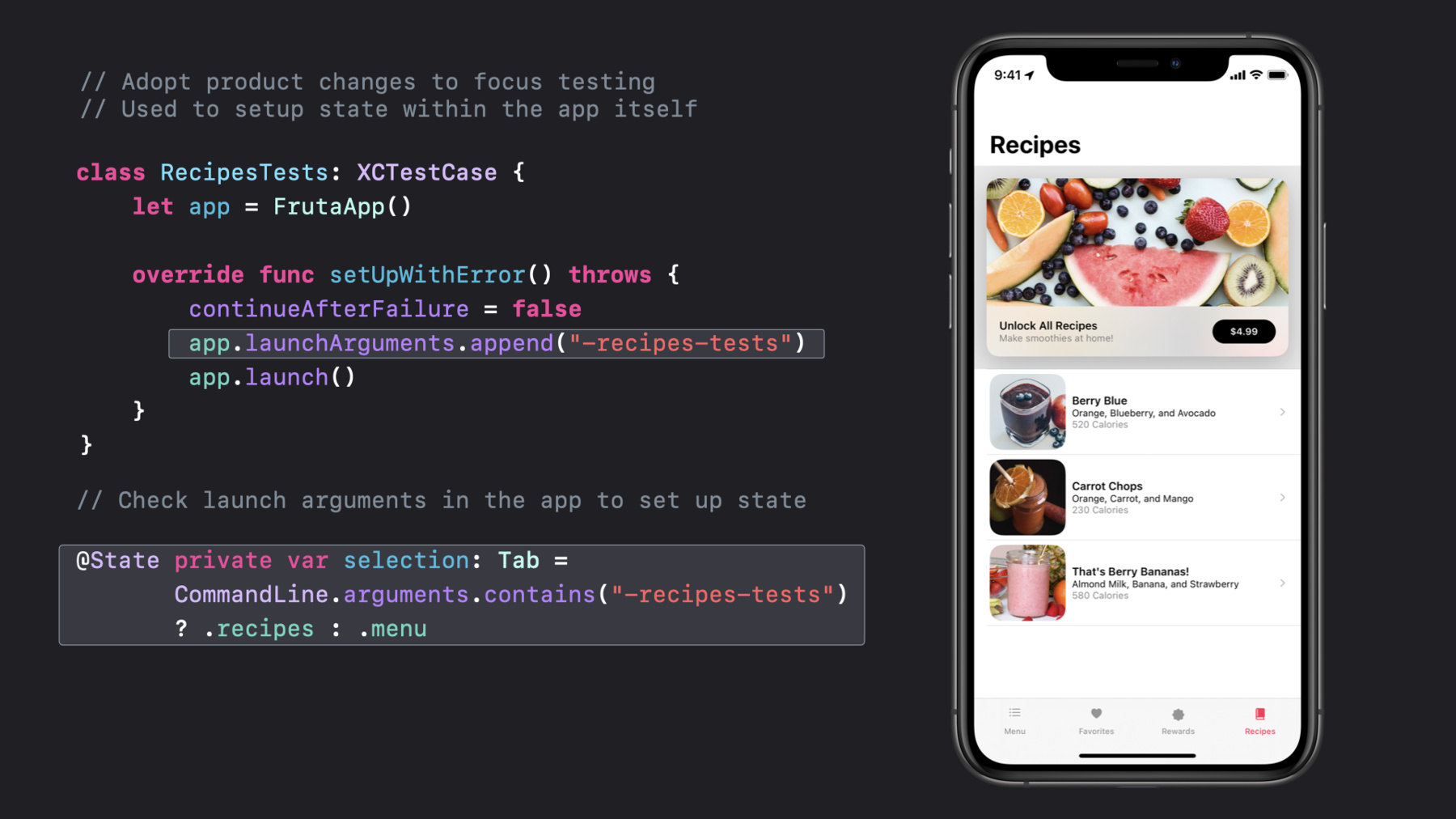

This helps me to find the first error faster instead of wading through multiple errors. I also use this as an opportunity to launch the app for each test in this class. One technique that I've incorporated is to leverage launchArguments and environment variables to set up state within my app quickly. This should not be used to set all state, but there may be cases where it's needed, like bypassing two-factor authentication during testing. In this case, I'm using it as a way to bypass the Menu tab, and instead, start from the Recipes tab. Small changes like this can improve the speed of running my tests by avoiding unnecessary work, but more importantly, it avoids me having to triage failures that might be happening in the Menu tab while I'm expecting to see results for testing my Recipes tab.

To recap, I'm using setUpWithError throws to improve error handling. I perform common setup tasks for every test in the class like launching the app.

I'm using launchArguments to communicate with the app to set state. And I adopt product changes to quickly setup state and focus testing. The next step is to run our tests.

Tests should be focused on doing an action and then asserting that the action completed.

Let's start with how I can make my actions easier to triage. The first thing I consider is that each test should have a specific goal in mind. That goal should be reflected in the title of the test. In this case, I'm testing the ingredients list for accuracy. The only action my test needs to perform is to select the Berry Blue Recipe. Minimizing the actions makes it easier to triage failures later.

Tapping this row brings up the recipe and I can verify the ingredient list as a result of my action. As such, in my result bundle, I can easily see what the test is validating thanks to the name of my test.

Speaking of naming, over the years, I've found that the labels of UI elements change often, so as a preventative measure, I use enums for all string values. That way, when the UI changes, I can easily update my tests to react to those changes. This not only saves me time to update my tests to UI changes, it has also minimized the number of times I've dealt with one test failing due to a spelling mistake that was hard to recognize. Just like collecting all the strings into enums, another way that I've minimized mistakes is by factoring common code into helper functions, so that multiple tests can use the same code path. In this case, multiple tests need to access the Smoothie List in the app, and to select a recipe. Pulling out this common testing path means that rather than duplicating code, I can spend my efforts hardening these paths to reduce test errors. Another technique I've employed is to model the domain of my app and design a test language around that domain. Then my test reflects the language of my app. In this example, I can ask my Fruta app for it's Smoothie List, and I can do an action on my Smoothie List like select a recipe, which returns the Recipe UI element. These are based on the FrutaUIElement class I've created to keep track of the app and the element at a lower level. In this way, I've made my shared code object-oriented-ish. While testing is treated as very functional and based on elements and queries, I can simulate an object-oriented environment for readability. Doing so, gives me the ability to make calls from my test that map to how I think of my app, as a series of subviews. The result of doing this modeling is that I'm working with a reduced hierarchy with each element and can focus my queries on just the subelements of that element.

Over the years, our shared testing code has become quite large.

So, to deal with that, we treat it like our product code and have created a shared framework for our tests. You may also consider using a Swift package to share your testing code, especially if you're sharing code between multiple applications.

To recap this section, I design tests for a specific goal to focus what I'm testing. I'm using enums and factoring common code into helper functions to simplify resolving UI changes. I'm modeling objects in my tests to reflect the UI hierarchy of my app. And I'm using a framework, or you can use a Swift package, to share code between projects. Now, let's look at my favorite section: test assertions. Because this is where we are actually doing the heart of our testing.

Here are some of the lessons I've learned with test assertions and error handling for making test failures easily triage-able. One small thing that has helped me immensely is to use the optional message in XCTAssert functions. Leaving out the message is fine when I'm triaging tests at my desk, but when all I have is the result bundle, there's a lot of context missing. In this case, I know that three is not equal to two, but two what? If I add a message, I can add context. Humans are reading my assertion messages most of the time, and it's often me, so I like to leave myself a clue as to why this expression failed. However, sometimes, my assertion failures are read by automation systems, in which case, I want my messages to be specific, but not too specific.

So, I leave out things like date/time stamps or unique file paths so that assertion messages can be used to recognize multiple tests that are failing for the same reason.

I also try to make sure that I am using the correct assertion for what I'm trying to accomplish. Doing so ensures that the automatic message that I see when it fails is more relevant. In Xcode 12, we added XCTIssue which is a new low-level way of reporting failures. For more information, watch the related video, "Triage Test Failures with XCTIssue." One of the pitfalls of asserting that I've come across is asynchronous events. I've sometimes had difficulty triaging asynchronous events. In this case, I tap the recipe button, but it may take a while to load depending on what my code is doing. If I immediately return the recipe element, it may not exist yet. In the past, I've used sleep to give my test a little built-in time. However, I wouldn't sleep on the job, so why let my tests do it? And it delays getting my results faster. XCTest has built-in retries, but depending on my app code, it might not be enough. So, I prefer to use waitForExistence with a timeout. This provides polling so that if the expectation is true earlier than the timeout, then I've saved that much time waiting. It also allows my test to pass or fail deterministically in an environment I've designed. In the result bundle, I'm able to see that my test waited five seconds to find the Ingredients View. Another recommendation is to unwrap optionals. In this example, I want to return the count of the favorites in a string array that is passed in, however, I didn't take the time to unwrap my optional. When I'm running the code locally, this results in a crash and halts my tests, which is really unfortunate if I set them to run while I went to get lunch and they didn't finish when I returned. When this happens in a continuous integration environment, I get a result bundle with a failing test that reads, "Test crashed with signal ill." I can easily avoid this situation by making sure that I unwrap my optionals. I can use the Swift-provided methods of unwrapping optionals such as "if let", where I can then use the unwrapped value in the if-block.

If I want to use the unwrapped variable later, I can use "guard let". This allows me to throw an error that I provide in the guard-block if I encounter nil.

The third option is using the nil-coalescing operator, which allows me to provide a default value if I encounter nil, in this case, an empty array.

The fourth option, is to use XCTUnwrap, which is provided by the XCTest framework. It's a simplification of "guard let" where it throws an error if my test encounters nil.

Using XCTUnwrap shows my comment from the call in addition to the auto-generated message in my result bundle. The best part about unwrapping optionals is that by failing gracefully instead of crashing, my tearDown method will be called. Speaking of failing gracefully, let's talk about throwing errors.

In my tests, the rule is that I always throw instead of assert from shared code. The reason is because the shared code is being run from many tests, and in some of those tests, I may purposely be testing negative test cases to ensure something hidden isn't shown or to force an error dialog to appear for testing purposes. So, in a case like this, where I have a shared method to verify the ingredients, I may be testing a bug where I had extra ingredients showing previously, and I'm testing that those extra ingredients aren't showing up anymore. So, I throw an error. In my errors, I often pass in values that I want to appear in my error descriptions, which are a requirement of the CustomStringConvertible protocol. Using the description function means that I see a more contextually relevant error in the result bundle for those times I'm not triaging my results locally. If I am triaging locally, then new in Xcode 12 is the ability to see the backtrace for errors directly in my code, so I don't have to wonder anymore where the error is actually hiding in my shared code. I can also find a backtrace in the Runtime Issues Navigator as well as the result bundle. To learn more about how to leverage the testing backtraces, see the related video, "Triage Test Failures with XCTIssue." Also in this result bundle, is a user-readable disclosure group that my code added to provide more context of what action I was taking at the time. I can easily see here that I was looking for Grape in my Berry Blue smoothie, which is definitely wrong. To provide myself little breadcrumbs like this, I use XCTContext.runActivity and provide a name. This is what appears in the result bundle along with any actions performed in its block. This is a great way to add some organization and context to my result bundle and make it easy to read according to the actions my test is taking. Another thing I can do with the runActivity is to add attachments with XCTAttachment. I can add attachments like files, images, and data to my XCTContext or the test case and it will show up in a result bundle. It's a great way to gather extra logging for a failed test especially when it's coming from a CI system. Earlier I said not to add file paths into assert comments because instead, I can add both the file path and the file itself as an attachment.

This makes it easier to triage the failures later.

I believe that tests should be responsible for gathering all the data needed to triage the product failures because that data may not be available later. Now sometimes, a test shouldn't run at all and for that I use XCTSkip, XCTSkipUnless, and XCTSkipIf for documenting tests that aren't running by adding the optional message. The main use is to skip tests that aren't relevant to the platform my tests are running on. Some alternatives that I've used in practice are for stubbing out tests I want to write for a new feature, which allows me to see which tests are unimplemented versus what tests regressed. The third is that there are sometimes tests that just can't be fixed for now, for various reasons, and I don't want to continue triaging the failures, but I also don't want to lose track of the test by disabling it. Using XCTSkip allows me to continue to see the skipped test in the result bundle so that I don't forget that I need to write the test or fix it when the issue is resolved.

To recap this section, I like to add assertion messages and use the relevant XCTAssert functions to add context to the failures in my result bundle. I definitely unwrap my optionals to ensure that my tests don't crash while I went to lunch, but also so that my tearDown methods are called.

I use the waitForExistence method for asynchronous events and timing issues instead of sleep.

I throw errors from shared code instead of asserting so that other tests using that code can catch the errors for negative testing.

I use XCTContext.runActivity and attachments for adding more context and content to my result bundles.

And I use XCTSkip for tests that just aren't expected to be running in the current scenario. Lastly, let's look at tear down. Since most of my work is already done, there are only three recommendations I have for tear down. The first is that I've modernized my tests to use tearDownWithError that throws to take advantage of the new error management. I use the tearDown method as a time to collect additional logging, including some analysis of the failures. And this is when I reset the environment from the changes I made during setup. To recap this video, we looked at set up, where I change the environment and confirm my assumptions needed for my test.

Test actions are where I perform the necessary actions I want to test through shared code modeled after my app.

I then verify that the actions completed properly by using helper methods, errors, and test assertions.

Then, I finished with the tearDown method to gather data and clean up after my test. I hope that these techniques and recommendations help you to make your tests more robust and to easily and quickly triage your product issues so that your tests turn green and you can ship a quality product. Thank you.

-

-

1:58 - Use setUpWithError()

class RecipesTests: XCTestCase { let app = FrutaApp() override func setUpWithError() throws { continueAfterFailure = false app.launchArguments.append("-recipes-tests") app.launch() } } -

3:09 - Use launch arguments

class RecipesTests: XCTestCase { let app = FrutaApp() override func setUpWithError() throws { continueAfterFailure = false app.launchArguments.append("-recipes-tests") app.launch() } } @State private var selection: Tab = CommandLine.arguments.contains("-recipes-tests") ? .recipes : .menu -

4:12 - Design tests for a specific goal

func testIngredientsListAccuracy() throws { // Select Berry Blue recipe let recipe = try app.smoothieList().selectRecipe (smoothie: .berryBlue) // Verify ingredients list try recipe.verify(ingredients: SmoothieType.berryBlue.ingredients) } -

4:56 - Use enums for string values

public enum SmoothieType : String { case berryBlue = "Berry Blue" case carrotChops = "Carrot Chops" case berryBananas = "That's Berry Bananas!" var ingredients : [String] { switch self { case .berryBlue: return ["Orange", "Blueberry", "Avocado"] case .carrotChops: return ["Orange", "Carrot", "Mango"] case .berryBananas: return ["Almond Milk", "Banana", "Strawberry"] } } } -

5:25 - Factor common code

let recipe = try app.smoothieList().selectRecipe(smoothie: .berryBlue) public class FrutaApp : XCUIApplication { public func smoothieList() throws -> SmoothieList { let element = tables["Smoothie List"] if !element.waitForExistence(timeout: 5) { throw FrutaError.elementDoesNotExist("Smoothie List table") } return SmoothieList(app: self, element: element) } } public class SmoothieList : FrutaUIElement { public func selectRecipe(smoothie: SmoothieType) throws -> Recipe { element.buttons[smoothie.rawValue].tap() return try app.recipe() } } -

5:49 - Model UI hierarchy in testing code

public class FrutaApp : XCUIApplication { public func smoothieList() throws -> SmoothieList {  } } public class SmoothieList : FrutaUIElement { public func selectRecipe(smoothie: SmoothieType) throws -> Recipe {  } } open class FrutaUIElement { let app: FrutaApp let element: XCUIElement init(app: FrutaApp, element: XCUIElement) { self.app = app self.element = element } } -

8:17 - Use assertion messages

XCTAssertEqual(count, expectedCount, "\(SmoothieType.berryBlue.rawValue) smoothie is expected to have \(expectedCount) ingredients: \(expectedIngredients), however, there were \(count) found.") -

9:21 - Asynchronous events

public func selectRecipe(smoothie: SmoothieType) throws -> Recipe { element.buttons[smoothie.rawValue].tap() return try app.recipe() } public func recipe() throws -> Recipe { let element = scrollViews["Ingredients View"] if !element.waitForExistence(timeout: 5) { throw FrutaError.elementDoesNotExist( "Ingredients View scroll view") } return Recipe(app: self, element: element) } -

10:19 - Unwrapping optionals

func countFavorites(favorites: [String]?) -> Int{ let favs = favorites! return favs.count } -

10:56 - Unwrapping optionals continued

if let favs = favorites {  } guard let favs = favorites else { /* throw an error */ } let favs = favorites ?? [] let favs = try XCTUnwrap(favorites, "favorites is nil, so there is nothing to count”) -

12:19 - Throw errors from shared code

public func verify(ingredients: [String]) throws { try XCTContext.runActivity(named: "Verifying \(ingredients) exists in the Recipe screen.") { verifyingRecipe in for ingredient in ingredients { if !element.switches[ingredient].waitForExistence(timeout: 5) { throw RecipeError.ingredientDoesNotExist(ingredient) } } } } public enum RecipeError : Error, CustomStringConvertible { case ingredientDoesNotExist(String) public var description : String { switch self { case .ingredientDoesNotExist(let ingredient): return "\(ingredient) does not exist in the Ingredients View.)" } } } -

13:41 - Use XCTContext.runActivity()

public func verify(ingredients: [String]) throws { try XCTContext.runActivity(named: "Verifying \(ingredients) exists in the Recipe screen.") { verifyingRecipe in for ingredient in ingredients { if !element.switches[ingredient].waitForExistence(timeout: 5) { throw RecipeError.ingredientDoesNotExist(ingredient) } } } -

14:02 - Add attachments to the result bundle

public func verify(ingredients: [String]) throws { try XCTContext.runActivity(named: "Verifying \(ingredients) exists in the Recipe screen.") { verifyingRecipe in for ingredient in ingredients { if !element.switches[ingredient].waitForExistence(timeout: 5) { let attachment = XCTAttachment(string: element.debugDescription) verifyingRecipe.add(attachment) throw RecipeError.ingredientDoesNotExist(ingredient) } } } -

14:50 - Use XCTSkip

let debuggingTests = false func testSelectSmoothie() throws { try XCTSkipUnless(debuggingTests == true, "This test is not yet implemented.") }

-