-

Data Essentials in SwiftUI

Data is a complex part of any app, but SwiftUI makes it easy to ensure a smooth, data-driven experience from prototyping to production. Discover @State and @Binding, two powerful tools that can preserve and seamlessly update your Source of Truth. We'll also show you how ObservableObject lets you connect your views to your data model. Learn about some tricky challenges and cool new ways to solve them — directly from the experts!

To get the most out of this session, you should be familiar with SwiftUI. Watch “App essentials in SwiftUI” and "Introduction to SwiftUI"Resources

Related Videos

WWDC22

WWDC21

WWDC20

-

Search this video…

Hello and welcome to WWDC.

Hello, and welcome to Data Essentials in SwiftUI. I'm Curt Clifton, an engineer on the SwiftUI team. Later I'll be joined by my friends and colleagues, Luca Bernardi and Raj Ramamurthy.

We're going to cover three main areas in this talk. I'll talk about getting started on the data flow in your SwiftUI app, and cover topics like State and Binding. Then Luca will discuss how you can build on those ideas and more to design the data model for your app. Finally, Raj will share techniques for integrating your data model into your app. Along the way, we'll discuss the life cycle of a SwiftUI view and share several cool, new features that make it even easier to model your data. We'll also help you develop a deeper understanding of how value and reference types in Swift interact with data flow in SwiftUI.

I'll be walking through some basic data flow features in SwiftUI, and we'll cover some questions you should ask yourself whenever you create a new SwiftUI view. Luca is really into book clubs. He's so into them that he decided he needed an app to keep track of what each of his clubs is reading and take some notes for their next meeting. I enjoy reading too, and thought it would be fun to work on an app together.

To get started, I want to prototype the view that represents a book I'm reading. When I start on a new view in SwiftUI, there are three key questions I like to think about.

What data does this view need to do its job? In this example, the view needs a thumbnail of the book cover, the title, the author's name, and the percentage of the book that I've read.

How will the view manipulate that data? This view just needs to display the data. It doesn't change it.

Where will the data come from? This is the "Source of Truth". In the examples throughout this talk, Luca, Raj and I will use this badge to label the source of truth.

Ultimate, as we'll see, this question of the source of truth is the most important one in the design of your data model. Let's build out this view and see what its source of truth should be.

So what data does this view need to do its job? The book value provides the name of the cover image, the author and the title.

The progress value provides the percent complete.

And how will the view manipulate this data? It just displays the data, it doesn't change it, so these can be "let" properties.

And where will the data come from? It will be passed in from the superview when the BookCard is instantiated.

The source of truth is somewhere farther up the view hierarchy. The superview passes the true data in when it instantiates a BookCard. A new BookCard is instantiated every time the superview's body executes. The instance lives just long enough for SwiftUI to render it, then it's gone.

We can visualize the internal structure using a diagram. The boxes on the left represent the SwiftUI views that are composed to build this BookCard.

The capsules on the right represent the data that's used to render the views. We'll return to diagrams like this throughout the talk.

Next, I'd like to look at a slightly more interesting view. When I tap on a book, the app takes me to this screen where I can review my progress. I want to add a way to update my progress, and add notes when I tap on the "Update Progress" button. Something like this.

Let's look at how the parent view and this sheet work together.

We'll focus on how the sheet is presented.

When the user taps the "Update Progress" button, we'll call the presentEditor method. It will mutate some state to cause the sheet to appear.

What data does this view need to control the presentation of the sheet? We need a Boolean to keep track of whether the sheet is presented, and we need a String to keep track of the note, and a Double to track the progress. Whenever I have multiple related properties like this, I like to pull them out into their own struct.

Besides making BookView more readable, there are two other great things about this approach. We get all the benefits of encapsulation. EditorConfig can maintain invariants on its properties and be tested independently. And because EditorConfig is a value type, any change to a property of EditorConfig, like its progress, is visible as a change to EditorConfig itself.

Our next question is, how will the view manipulate this data? When the "Update" button is tapped, we'll need to set isEditorPresented to "True" and update progress to match the current progress.

Because we extracted the state into the EditorConfig struct, we can make it responsible for those updates, and just have the BookView ask the EditorConfig to do the work.

Then, we'll add a mutating method to EditorConfig, like so.

And where will the data come from? Well, the editor configuration is local to this view. There isn't some parent view that can pass it in, so we need to establish a local source of truth. The simplest source of truth in SwiftUI is State.

When we mark this property as State, SwiftUI takes over managing its storage. Let's look at that as a diagram.

Again, we have the views represented by these boxes on the left, and the data by a capsule on the right. Notice that the capsule has a thick border. I'm using this border to indicate data that's managed by SwiftUI for us. Why is that important? Well, remember that our views only exist transiently. After SwiftUI completes a rendering pass, the structs themselves go away.

But because we marked this property as State, SwiftUI maintains it for us. The next time the framework needs to render this view, it reinstantiates the structs, and reconnects it to the existing storage.

Let's look at the ProgressEditor next.

What data does the ProgressEditor need to do its job? Well, all the data from an EditorConfig. And how will the view manipulate that data? It needs to change it, so we'll use a var.

And where will the data come from? That's an interesting question in this case. Back to the diagrams.

Let's focus on the BookView and the ProgressEditor. Suppose we just pass the EditorConfig down to the ProgressEditor as a regular property.

Because EditorConfig is a value type, Swift would make a new copy of the value. Any changes the ProgressEditor made to the note, or the progress, would only change this new copy, not the original value that SwiftUI is managing for us. So this doesn't allow ProgressEditor to communicate with BookView.

What next? Ah! What if we gave ProgressEditor its own State property? That seems like it might be what we want. It tells SwiftUI to manage a new piece of data for us.

Sadly, this is also wrong. Remember, State creates a new source of truth. Any changes made by the ProgressEditor would be made to its own state, not the one shared with BookView. We want a single source of truth.

We need a way to share write-access to the source of truth from BookView with ProgressEditor. In SwiftUI, the tool for sharing write-access to any source of truth is Binding. BookView creates a Binding to EditorConfig. A read-write reference to the existing data and shares that reference with ProgressEditor.

By updating the EditorConfig through this Binding, the ProgressEditor is mutating the same state that BookView is using. SwiftUI notices changes to the EditorConfig. It knows that both BookView and ProgressEditor have a dependency on that value, and so it knows to re-render those views when the value changes.

The ProgressEditor needs to pass data back to the BookView.

We've just seen that Bindings are the right tool for this task.

The dollar sign in the call creates a Binding from the State because the projected value of the State property wrapper is a Binding.

The Binding property wrapper creates a data dependency between the ProgressEditor and the EditorConfig state in BookView. Many built in SwiftUI controls also take Bindings. For example, the new TextEditor control used for our notes takes a Binding to a String value. Using the dollar sign projected value accessor, we can get a new Binding to the note within the EditorConfig.

SwiftUI lets us build a new Binding from an existing Binding. Remember, Bindings aren't just for State.

That's a bit on getting started with data flow in SwiftUI. Remember to ask yourself the three questions when adding a SwiftUI view. What data does this view need? How will it use that data? And where does the data come from? You can use properties for data that doesn't change. Use State for transient data owned by the view. Use Binding for mutating data owned by another view.

Now I'd like to turn things over to Luca to dive into designing your data model because State is not the whole story.

Thank you, Curt. Ciao, everyone. My name is Luca. My colleague, Curt, has just described how to use State and Binding to drive changes in your UI, and how these tools are a great way to quickly iterate on your view code.

But State is designed for transient UI state that is local to a view. In this section, I want to move your attention to designing your model and explain all the tools that SwiftUI provides to you.

Typically, in your app, you store and process data by using a data model that is separate from its UI.

This is when you reach a critical point where you need to manage the life cycle of your data, including persisting and syncing it, handle side-effects, and, more generally, integrate it with existing components. This is when you should use ObservableObject. First, let's take a look at how ObservableObject is defined.

It's a class constrained protocol which means it can only be adopted by reference type.

It has a single requirement, an objectWillChange property. ObjectWillChange is a Publisher, and as the name suggests, the semantic requirement of the ObservableObject protocol is that the publisher has to emit before any mutation is applied to the object. By default, you get a publisher that works great out of the box. But if you need to, you can provide a custom publisher. For example, you can use a publisher for a timer, or use a KVO publisher that observes your existing model.

Now that we've seen the protocol, let's take a look at a mental model for understanding ObservableObject.

When your type conforms to ObservableObject, you are creating a new source of truth and teaching SwiftUI how to react to changes.

In other words, you are defining the data that a view needs to render its UI and perform its logic.

SwiftUI will establish a dependency between your data and your view, here represented with blue boxes.

SwiftUI uses this dependency to automatically keep your view consistent and show the correct representation of your data.

We like to think of ObservableObject as your data dependency surface. This is the part of your model that exposes data to your view, but it's not necessarily the full model.

If you think of ObservableObject this way, it doesn't need to be exactly your data model. You can separate your data from its storage and life cycle. You can model your data using value type and manage its life cycle and side effects with a reference type. For example, you can have a single ObservableObject that centralizes your entire data model and is shared by all your views, like in the diagram here. This gives you a single place for all your logic, making it easy to reason about all the possible states and mutations in your app. Or you can focus on part of your app by having multiple ObservableObject that offer a specific projection onto your data model are are designed to expose just the data that is needed. This works better when you have a complex data model and you want to provide a more tightly scoped invalidation to part of your app. Let's go back to the app we were building, and let's see how we can apply what we have just discussed. Let's bring back the view that Curt was working on before. This is the view that allows me to update my progress in the book and add some notes of things I found interesting during my reading session.

Curt focused on the data for the progress sheet. Let's look at the rest of the data we need for this view and how to use ObservableObject to add rich features, such as storing data on disk or syncing it with iCloud.

We can create a new class called CurrentlyReading that conforms to ObservableObject that stashes a book and its reading progress. This is the part of our model that we will expose to our view to present data and respond to changes. The specific book will never change, so we can just make this property a let. We want to be able to update the progress and have our UI react to it. We can do this just by annotating the progress property with the @Published property wrapper. Let's take a look at how @Published works.

@Published is a property wrapper which makes a property observable by exposing a Publisher.

For most models, you can just conform to ObservableObject, add @Published to the properties that might change, and you're done.

It's that simple to never have to worry about keeping your data in sync with your view.

When you use @Published with the default ObservableObject publisher, the system will automatically perform invalidation by publishing right before the value changes.

For advanced use cases, the projected value of @Published is a Publisher that you can use to build reactive streams.

Let's revisit the three questions that you should be asking when designing your data model.

With ObservableObject, answering the second question is pretty straightforward: we always assume mutability.

Let's now take a look at how to answer these other two questions when it comes to ObservableObject. We have seen how to define our model, but now we need to use it in our view.

SwiftUI offers three property wrappers that you can use in a view to create a dependency to an ObservableObject.

These tools are ObservedObject, StateObject, which is new this year, and EnvironmentObject. Let's start by taking a look at ObservedObject. ObservedObject is a property wrapper that you can use to annotate properties of your view that holds a type conforming to ObservableObject. Using it informs SwiftUI to start tracking the property as a dependency for the view.

You are defining the data that this view will need to do its job.

This is the most simple and flexible of the tools. ObservedObject does not get ownership of the instance you're providing to it, and it's your responsibility to manage its life cycle. Let's see how to use it in our app. Here I have my BookView. It's the view that displays the book and all the progress I've logged so far. From this screen, I can also update my progress for this book. We can add a property of the type currentlyReading, the type we have just created, and annotate it with the @ObservedObject property wrapper. The instance that is assigned to this property is going to be the source of truth for this view.

Now, we can read the model in the view body. SwiftUI will guarantee that the view is always up to date. There is no code that you have to write, and there is no event to manage to keep your view in sync. You can just declaratively describe how to write the view from the data, and SwiftUI will take care of all the rest. My colleague, Raj, will go into more detail about the SwiftUI update life cycle, but I want to take you behind the scene and show you what SwiftUI is doing for you.

Whenever you use ObservedObject, SwiftUI will subscribe to the objectWillChange of that specific ObservableObject. Now, whenever the ObservableObject will change, all the view that depends on it will be updated. One of the questions that we often get is "why 'will' change? Why not 'did' change?" And the reason is that SwiftUI needs to know when something is about to change so it can coalesce every change into a single update. But how do we produce mutation? Many of the UI components vended by SwiftUI take a Binding to a piece of data and, earlier in the talk, you have seen an example of how to design your component to do the same. This is one of the fundamental design principles of SwiftUI. Accepting a Binding allows a component read and write access to a piece of data while preserving a single source of truth.

Curt has shown you how to derive a Binding from State. Doing the same with ObservableObject is just as easy.

You can get a Binding from any property that is of value type on an ObservableObject just by adding the dollar sign prefix in front of your variable and accessing the property. Let's see a concrete example in our book club app.

One of the great satisfactions when reading a book is finishing that last chapter, and I want a grand gesture to mark this event. I can't think of anything better than tapping on a Toggle to say, "I'm done with this book." The first thing I need to change is my model. We can just add a new property, "isFinished" and annotate it with @Published so that whenever its value changes, our UI will reflect the change. Let's see how we can change BookView to add this feature. I can add a Toggle with a nice label to allow me to mark this book as done. The Toggle expects a Binding so that it can show the current state and when the user taps on it, it can mutate the value. We can provide a Binding to "isFinished" just by adding the dollar sign prefix to currentlyReading and accessing the "isFinished" property. Now, whenever the user interacts with the Toggle, currentlyReading will be updated and SwiftUI will update all the views that depend on it. For example, in this view, we will disable the button to update the progress when we are done reading the book. Throughout our app, we are shown these beautiful book covers, and we want to load them asynchronously from the network, just before they are displayed on screen.

They're expensive resources, so we want to keep them alive only while the view is visible.

More generally, we noticed that often you do want to tie the life cycle of your ObservableObject to your view, like with State.

If you recall, ObservedObject does not own the life cycle of its ObservableObject, and so we wanted to provide a more ergonomic tool.

This tool is StateObject, which is new this year.

When you annotate a property with StateObject, you provide an initial value, and SwiftUI will instantiate that value just before running body for the first time. SwiftUI will keep the object alive for the whole life cycle of the view.

This is a great addition to SwiftUI and let's see how we can use it in practice. Let's create a CoverImageLoader class to load a specific image by name. Here I'm just showing the skeleton of this class, but not how I made it an ObservableObject and annotated the property that holds the image with @Published.

Once we have our image, SwiftUI will automatically update the view.

And now in our view, we can use CoverImageLoader and just annotate the property with StateObject. CoverImageLoader will not be instantiated when the view is created. Instead, it will be instantiated just before body runs and kept alive for the whole view life cycle. When the view is not needed anymore, SwiftUI will release the CoverImageLoader as expected. You don't need to fiddle with onDisappear anymore. Instead, you can use the ObservableObject lifetime to manage your resources. In SwiftUI, views are very cheap. We really encourage you to make them your primary encapsulation mechanism and create small views that are simple to understand and reuse.

This means that you might end up with a deep and wide view hierarchy, like in the diagram here. If we look at this through the perspective of data flow, you might need to create an ObservableObject high up in the view hierarchy and pass the same instance to many views.

Sometimes, you need to you use your ObservableObject in a distant subview and passing it down through views that don't need the data can be cumbersome and involve a lot of boilerplate. Luckily, we have a solution for this problem with EnvironmentObject. EnvironmentObject is both a view modifier and a property wrapper. You use the view modifier in a parent view where you want to inject an ObservableObject. And you use the property wrapper in all the views where you want to read an instance of that specific ObservableObject. The framework will take care of passing that value everywhere it's needed and track it as a dependency only where it's read.

In this part of the talk we have seen how to design your model using ObservableObject and how SwiftUI provides all the fundamental primitives that you can use to build the best architecture for your needs.

We have seen how to create a dependency between a view and a piece of data, how with the new StateObject property wrapper you can tie the life cycle of an ObservableObject to a view, and finally, how EnvironmentObject gives you the convenience to flow ObservableObject in your view hierarchy. Now I'm going to hand it over to Raj. He's going to dive deep into SwiftUI's life cycle and how it relates to performance, how to handle side effects and some exciting new tools. Thank you, everyone, and have a great WWDC. Raj? Thanks, Luca. You've learned how to get started with data in SwiftUI and how to design a great model. Now, I'd like to tell you how to design for the best performance, as well as some further considerations in choosing a source of truth. To begin with, let's talk about views and their role in the SwiftUI system. A view is simply a definition of a piece of UI. SwiftUI uses this definition to create the appropriate rendering.

SwiftUI manages the identity and the lifetime of your views. And because a view defines a piece of UI, they should be lightweight and inexpensive. In the book club app, like in every app, everything on screen is a view.

Note that the lifetime of a view is separate from the lifetime of a struct that defines it.

The struct you create that conforms to the View protocol actually has a very short lifetime. SwiftUI uses it to create a rendering, and then it's gone.

Let's use a diagram to illustrate the importance of making views lightweight.

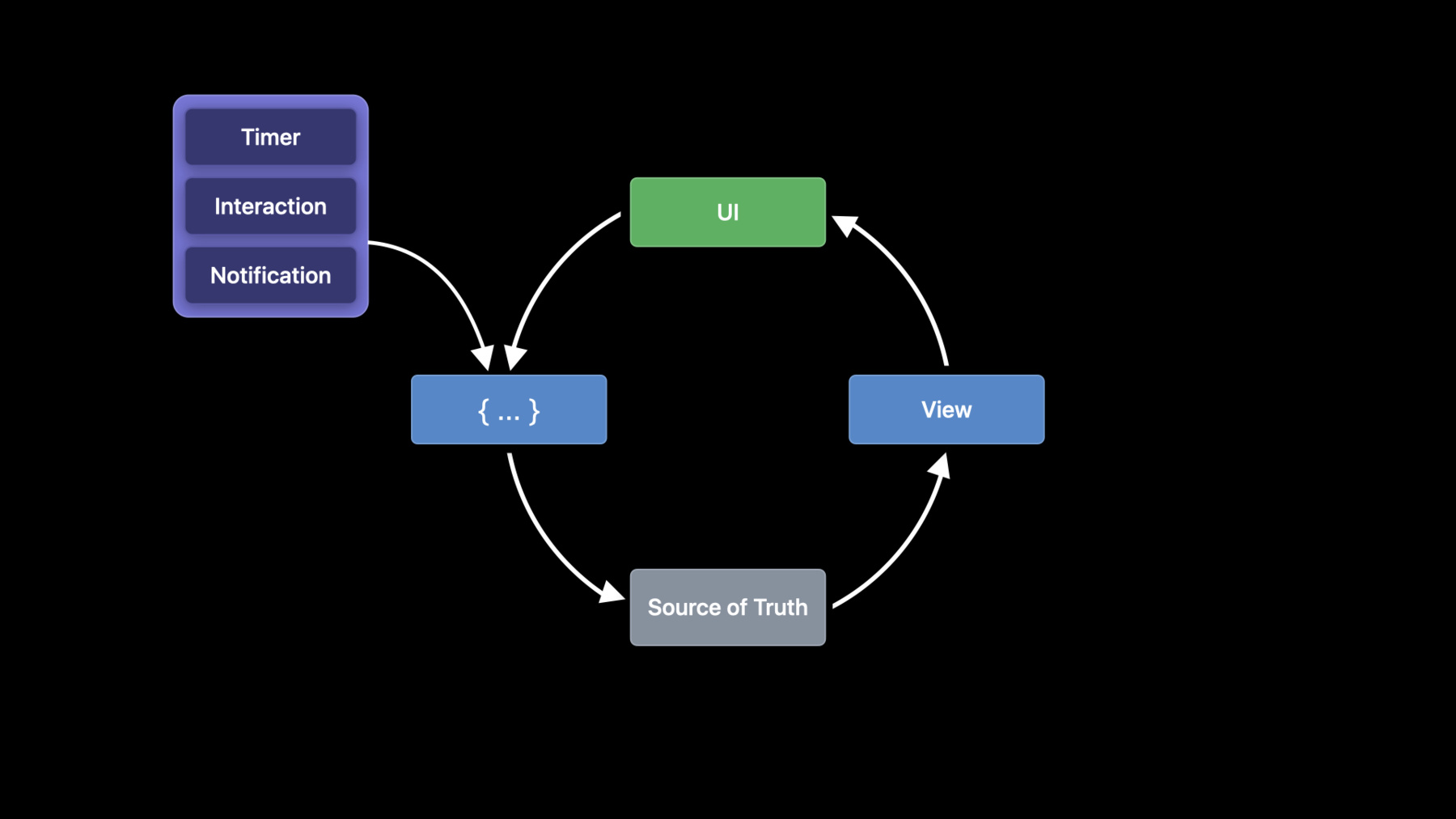

This diagram shows the SwiftUI update life cycle. Starting at the top, we have your UI. Moving counterclockwise, an event comes in which causes some closure or action to run. That then results in a mutation of a source of truth.

Then once we've mutated the source of truth, we'll get a new copy of the view, which we'll use to produce a rendering. That rendering is your UI.

That's just the basics. We'll revisit the diagram in a bit. For now, let's simplify it. And a little bit more.

Ah. Much better.

As the name implies, this life cycle is a cycle. It keeps repeating many times while your app is running.

This cycle is also really important for performance...

and ideally, the cycle carries on smoothly, like this.

But if there's expensive blocking work at any of these points, the performance of your app will suffer.

We call this a slow update. It means you might drop frames or your app might hang.

So how do you avoid slow updates? Well, the first thing you can do to avoid slow updates is to ensure that your view initialization is cheap.

A view's body should be a pure function, free of side effects. That means you should simply create your view description and return. No dispatching, no other work. Just create some views and move on.

Avoid making assumptions about when and how often body is called. Remember, SwiftUI can be pretty smart sometimes, which means it might not call body in line with your assumptions.

To illustrate the importance of body being cheap, let's look at an example.

Here's a simplified example of what our Currently Reading list might look like. In the ReadingListViewer, we'll define body as a NavigationView with the ReadingList within. Then, in ReadingList, we'll use an ObservedObject to generate the data.

This seems pretty reasonable, but there's actually a bug lurking here. Can you see it? It turns out whenever the body of ReadingListViewer is created, you're going to incur a repeated heap allocation of ReadingListStore, and this can cause a slow update.

Remember from earlier that your view structs do not have a defined lifetime, so when you write this, you're actually going to create a new copy of the object every time. And a repeated heap allocation like this can be expensive and slow. It also causes data loss because the object is reset every time.

Okay, so we've identified a problem, but how do we fix it? Well, in the past you had to create the model somewhere else and pass it in. But wouldn't it be great if you could just do this inline? I'm happy to tell you that this year we have a tool to solve this problem, called StateObject, and as Luca explained earlier, StateObject lets SwiftUI instantiate your ObservableObjects at the right time, so you don't incur unnecessary heap allocations, and you don't lose data.

This means you can get great performance and correctness.

One thing to note: We are declaring a new source of truth here, so let's slap the badge on it.

All right, let's bring back the diagram again.

And enhance.

Great. One thing to note is there are multiple sources of the events at the top left. Your app might react to an event generated by user interaction, such as tapping a button, or it might react to a publisher firing, like a timer or a notification. Regardless of what triggers the event, the cycle is still the same. We'll mutate a source of truth, update the view and then produce a new rendering. These triggers are called event sources. They are the drivers of change in your views. As I mentioned, a good example of this is user interaction or a publisher, such as a timer. And new this year, we have new ways to react to events, such as changes to the environment and bindings, and new ways to handle URLs and user activities.

Each of these modifiers takes a parameter, such as a publisher or a value to compare, and it also takes a closure.

SwiftUI will run the closure at the right time to help you avoid slow updates and keep body cheap. However, note that SwiftUI will run these closures on the main thread, so if you need to do expensive work, consider dispatching to a background queue.

We're not going to go into detail on these today, but I encourage you to check out the documentation to learn more.

So that's a bit on how to avoid slow updates and how to design for great performance. Next, let's bring back those three questions.

So we've largely covered how to solve the first two questions, but the third one isn't as easy.

When you answer this question, you're making a decision about the source of truth that you're going to use. And this is a hard question.

There's no one right answer here, so to help, I'd like to walk through some considerations.

An important question to ask is, who owns the data? Is it the view that uses the data, or maybe an ancestor of that view? Perhaps it's even another subsystem of your app.

A few guidelines here: As mentioned earlier, share data with a common ancestor. Also, prefer StateObject as a view-owned source of truth for your ObservableObjects. Lastly, consider placing global data in the app. We'll cover this next.

Now let's talk about data lifetime. We'll cover tying data lifetimes to Views, Scenes and Apps. For more on SwiftUI Scenes and Apps, please refer to the "App Essentials in SwiftUI" session.

First, let's start with Views.

As we've shown you throughout this talk, Views are a great tool to tie your data lifetime to, and all of the property wrappers we've discussed today work with views. You can make use of the State and StateObject property wrappers to tie data lifetime to view lifetime. Next, let's talk about scenes.

Because SwiftUI's scenes each have a unique view tree, you can hang important pieces of data off the root of the tree. For example, you can put a source of truth on the view inside of a window group.

In doing so, each instance of the scene that the window group creates can have its own, independent source of truth that serves as a lens onto the underlying data model. This works great with multiple windows.

As you can see here, the two scenes have independent UI states that represent the same underlying data. So now, Luca can go to two online book clubs at the same time. Next, let's talk about Apps.

Apps are a powerful new tool this year in SwiftUI allowing you to write your entire app in just SwiftUI. But what's great about Apps is that you can use State and other sources of truth in an app, just like you do in a view. Let me show you an example.

Here, we'll create a global book model for our entire app by using the StateObject property wrapper. Whenever the model changes, all of our app's scenes, and consequently, all of their views, will update, and by writing this, we've created an app-wide source of truth. When considering where to put your source of truth, you might want to put it in the app if it represents truly global data.

Your data's lifetime is important, but that lifetime is tied to the lifetime of its source of truth, and in all of the previous examples, we've used tools like State, StateObject, and Constants.

But these have a limitation, which is that they're tied to the process lifetime, which means if your app gets killed or the device restarts, State won't come back.

To help solve this problem, new this year, we're introducing Storage.

These have an extended lifetime and are saved and restored automatically. Note, these are not your model. Rather, they are lightweight stores that you use in conjunction with your model.

Let's start by taking a look at SceneStorage.

SceneStorage is a per-scene scoped property wrapper that reads and writes data completely managed by SwiftUI. It is only accessible from within Views, which makes it a great candidate for storing lightweight information about the current state of your app. Let's take a look at an example.

Here's the book club app from earlier with two scenes side-by-side. The first thing to think about when using SceneStorage is, what do you really need to restore? In this case, all we need to save and restore is the selection. The names of the book, progress and the notes are all stored in the model, so we don't need to save and restore those. Let's jump to code.

Here you can see how we use SceneStorage to save and restore our selected state. We'll pass a key, which must be unique to the type of data we're storing. Then, we can use it just like State. SwiftUI will automatically save and restore the value on our behalf.

And since this behaves like State, we've actually declared a new source of truth here, and this time, it's a scene-wide source of truth.

Now, if the device restarts, or the system needs to reclaim resources backing a scene, the data will be available at the next launch, allowing Luca to pick up his book club activities right from where he left off. Now that you've seen SceneStorage in action, I'd like to discuss AppStorage. This is app-scoped global storage, which is persisted using UserDefaults. It's usable from anywhere, so you can access it from within your app or from within your view. AppStorage, like UserDefaults, is super useful for storing small bits of data, such as settings.

In our book club app, we've also decided to introduce some settings.

Let's take a look at how to use AppStorage to accomplish this.

In our Settings view, all we need to do is add the AppStorage property wrapper and give it a key. By default, this uses the standard user defaults, but you can customize it if you need to.

For more information, please refer to the documentation.

In this case, we'll set up an AppStorage for each of our two settings here. We'll give them each a unique key because they are independent pieces of data. When using SceneStorage and AppStorage, it's important that unique pieces of data have unique keys. And just like the other property wrappers, this is also a source of truth, which means we can get bindings to it, such as for use in a toggle. And now, whenever the data changes, it will automatically be saved and restored to and from user defaults.

We've seen a variety of tools today for Process Lifetime and Extended Lifetime, and you use each of the tools here to store UI-level state. For the storage types, please be careful not to store everything with them because persistence isn't free. I'd also like to call out one more tool, and that's ObservableObject.

We've designed ObservableObject to be very flexible, so you can use it to achieve super custom behaviors, such as backing the data by a server or by another service. And together, these tools form a family that gives you a high degree of freedom to choose what best suits your needs.

We've seen a lot of tools and uses of them today, but the main takeaway is that there isn't a one-size-fits-all tool. Each has its own set of traits, so a typical app will use a variety of tools. We've done just that in our book club app. We've used State for buttons and our progress view, StateObject for our currentlyReading model, SceneStorage for our selection, and AppStorage for our settings. It's important to think about what the properties of your data are and what the right source of truth to use is, and you should also try to limit the number of sources of truth to cut down on complexity. And finally, take advantage of bindings as a way to build reusable components. Remember, bindings are completely agnostic to their source of truth, which makes them a powerful tool for building clean abstractions. Now that you've learned the essentials, it's time to build a great model. Thank you.

And have a great WWDC.

-

-

2:09 - BookCard

struct BookCard : View { let book: Book let progress: Double var body: some View { HStack { Cover(book.coverName) VStack(alignment: .leading) { TitleText(book.title) AuthorText(book.author) } Spacer() RingProgressView(value: progress) } } } -

3:35 - EditorConfig

struct EditorConfig { var isEditorPresented = false var note = "" var progress: Double = 0 mutating func present(initialProgress: Double) { progress = initialProgress note = "" isEditorPresented = true } } struct BookView: View { @State private var editorConfig = EditorConfig() func presentEditor() { editorConfig.present(…) } var body: some View { … Button(action: presentEditor) { … } … } } -

5:59 - ProgressEditor

struct EditorConfig { var isEditorPresented = false var note = "" var progress: Double = 0 } struct BookView: View { @State private var editorConfig = EditorConfig() var body: some View { … ProgressEditor(editorConfig: $editorConfig) … } } struct ProgressEditor: View { @Binding var editorConfig: EditorConfig … TextEditor($editorConfig.note) … } -

13:15 - CurrentlyReading

/// The current reading progress for a specific book. class CurrentlyReading: ObservableObject { let book: Book @Published var progress: ReadingProgress // … } struct ReadingProgress { struct Entry : Identifiable { let id: UUID let progress: Double let time: Date let note: String? } var entries: [Entry] } -

15:36 - BookView

struct BookView: View { @ObservedObject var currentlyReading: CurrentlyReading var body: some View { VStack { BookCard( currentlyReading: currentlyReading) //… ProgressDetailsList( progress: currentlyReading.progress) } } } -

17:50 - CurrentlyReading with isFinished

class CurrentlyReading: ObservableObject { let book: Book @Published var progress = ReadingProgress() @Published var isFinished = false var currentProgress: Double { isFinished ? 1.0 : progress.progress } } -

18:21 - BookView with Toggle

struct BookView: View { @ObservedObject var currentlyReading: CurrentlyReading var body: some View { VStack { BookCard( currentlyReading: currentlyReading) HStack { Button(action: presentEditor) { /* … */ } .disabled(currentlyReading.isFinished) Toggle( isOn: $currentlyReading.isFinished ) { Label( "I'm Done", systemImage: "checkmark.circle.fill") } } //… } } } -

19:58 - CoverImageLoader

class CoverImageLoader: ObservableObject { @Published public private(set) var image: Image? = nil func load(_ name: String) { // … } func cancel() { // … } deinit { cancel() } } -

20:20 - BookCoverView

struct BookCoverView: View { @StateObject var loader = CoverImageLoader() var coverName: String var size: CGFloat var body: some View { CoverImage(loader.image, size: size) .onAppear { loader.load(coverName) } } } -

25:36 - ReadingListViewer (Bad)

struct ReadingListViewer: View { var body: some View { NavigationView { ReadingList() Placeholder() } } } struct ReadingList: View { @ObservedObject var store = ReadingListStore() var body: some View { // ... } } -

26:39 - ReadingListViewer (Good)

struct ReadingListViewer: View { var body: some View { NavigationView { ReadingList() Placeholder() } } } struct ReadingList: View { @StateObject var store = ReadingListStore() var body: some View { // ... } } -

30:52 - App-wide Source of Truth

@main struct BookClubApp: App { @StateObject private var store = ReadingListStore() var body: some Scene { WindowGroup { ReadingListViewer(store: store) } } } -

32:43 - SceneStorage

struct ReadingListViewer: View { @SceneStorage("selection") var selection: String? var body: some View { NavigationView { ReadingList(selection: $selection) BookDetailPlaceholder() } } } -

33:49 - AppStorage

struct BookClubSettings: View { @AppStorage("updateArtwork") private var updateArtwork = true @AppStorage("syncProgress") private var syncProgress = true var body: some View { Form { Toggle(isOn: $updateArtwork) { //... } Toggle(isOn: $syncProgress) { //... } } } }

-