-

What's New in iOS Design

Discover how to update your app's interface for Dark Mode to create beautiful and accessible apps. And learn how refinements to modal sheets and the new contextual menu UI can help improve usability and lead to more powerful and efficient workflows.

Resources

- Human Interface Guidelines: Layout

- Human Interface Guidelines: SF Symbols

- Human Interface Guidelines: Materials

- Human Interface Guidelines: Dark Mode

- Human Interface Guidelines: Multitasking

- Human Interface Guidelines: Modality

- Presentation Slides (PDF)

Related Videos

WWDC19

-

Search this video…

With iOS 13, the way that we design and build apps is going to change in some subtle but significant ways.

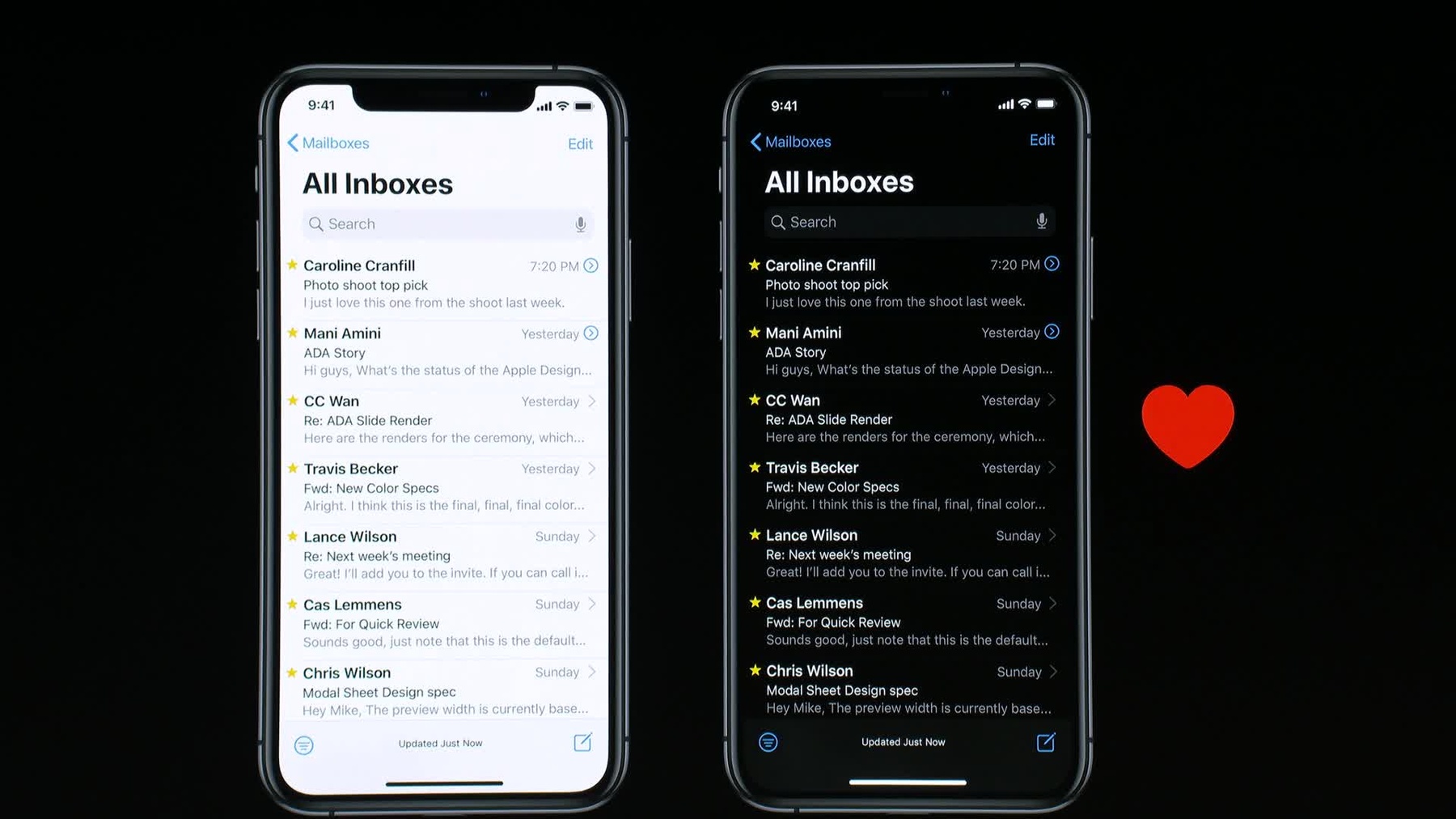

Dark Mode brings a new approach to how we work with colors, images, and text.

The new card-style sheets not only present modal presentations in a different way, but they change how we interact with them as well.

And the new contextual menu control makes it easy to quickly access contextually relevant functionality with ease. Now, between these three topics, we've got a lot of ground to cover, so let's dive in with Dark Mode.

Now, last year we introduced Dark Mode on macOS, and it was pretty popular. For many years, photo and video apps have used dark interfaces because they allow people to see photos and videos with clarity.

Dark UIs are great for dark lighting conditions; it's much easier for our eyes to adjust between a dark screen and the world around us. And, functional reasons aside, some people just prefer dark interfaces as a matter of personal preference.

Dark Mode on iOS uses a fully black background to provide maximal contrast with text and other foreground elements.

Black backgrounds blend in seamlessly with the hardware bezel to make your UI feel more expansive and integrated with the hardware itself.

In general, all of your apps should support Dark Mode. When the people using your app have set their device to be in Dark Mode, they'll expect your app to change as well.

Now, supporting Dark Mode involves moving towards the updated iOS design system which has been fully overhauled for iOS 13. Now, just so we're all on the same page, "design system" basically just means a set of parts like colors, fonts, and glyphs that work together in a logical and consistent manor.

A rational -- excuse me -- and consistent design system helps people to learn and use apps with ease.

By integrating with the iOS design system, your app will feel more familiar to people and be more understandable.

Now, before we get into all of the details, I'd like to share some of the key design goals that guided the design team's efforts.

First and foremost, they wanted iOS to remain familiar and intuitive. The iOS design system has received a complete makeover but the end result is still recognizably iOS.

They sought to provide more internal consistency. All of the built-in apps were redesigned to bring them into alignment with each other, using all of the components that we'll be talking about with you today.

They also wanted the new design system to include a range of color options to help successfully articulate information hierarchy, to allow the most important elements to be the strongest and the less important elements to recede.

They also put accessibility on equal footing with these other goals. The new system fully supports bold text and increased contrast accessibility modes.

And, lastly, they wanted the new design system to be simple, straightforward, and easy to implement.

All right, now let's get into the specifics.

Color seems like the right place to start.

Every app has a background, and most apps have text and glyphs. And some apps have separator lines and grouping boxes to help organize all of that content.

Now, when describing these colors, we can naturally talk about them by their values. The text is black, the background is white, etc., etc.

Now, as your interface gets a little bit more complicated, the length of that color palette extends. But that's not really an issue.

However, when you add support for separate appearance, you now have two parallel sets of colors to keep in sync with each other and manage.

At this point, it becomes helpful to think about color in a more abstract way.

This is where semantic colors comes in.

A semantic color describes the purpose of a color rather than what its value is.

Because semantic colors are extracted away from their exact appearance, they can work both -- they're dynamic.

So, a background color can be black in Dark Mode and white in Light Mode. So instead of maintaining two separate lists of colors for Light and Dark Modes, you can apply semantic colors from the system palette to UI elements and their appearance will automatically adapt between Light and Dark Modes, which is pretty convenient.

iOS 13 includes a palette of semantic colors for you to use.

Many of these colors have primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary values.

These variants are used to express information hierarchy. Label color has the most contrast with the background, so it's going to advance into the foreground and grab your attention and should be used for primary elements like titles, secondary for subtitles, tertiary for placeholder text, quaternary for disabled text.

The same basic principle applies to background colors. System background is a primary background color, and it's pure white in Light Mode and Pure Black in Dark Mode. Secondary and tertiary system background colors allow you to structure information hierarchically.

There's also a parallel set of background colors for grouped table views.

Now, if you observe closely, you'll note that the colors aren't simply inverted between Light and Dark Modes. The table row backgrounds are lighter in both. There was a concerted effort to select a palette of colors that assured contrast while at the same time keeping apps looking similar between Light and Dark Modes.

When you're designing for Dark Mode, it's often helpful to think about the lights as having been dimmed rather than everything being flipped inside out. The new system palette includes fill colors and separator colors. All of the fill colors and one of the separator colors are semi-transparent, which helps them to contrast well against variable background colors.

The new palette includes six, fully opaque gray values. These colors are best used when transparency would lead to undesirable results. So, for example, when drawing intersecting grid lines, overlapping semi-transparent colors can create distracting optical illusions.

And, if elements overlap, solid colors are really helpful and prevent things from looking disabled or broken.

These colors are used throughout the system for basically everything, and we encourage you to use them in your apps.

To get you started, you can check out the full color palette in the Apple Design Resources and the Human Interface Guidelines. I'll have more information about those at the end of the presentation.

As before, we will continue to provide tint colors for you to use as your app's tint color. These tint colors are dynamic, meaning that they have variants for Light and Dark Modes.

Each tint color has high-contrast variants. When they increase contrast, accessibility setting is enabled.

Tint colors get lighter in Dark Mode and darker in Light Mode.

Now, if you opt to pick your own tint color, try to select colors that work well in both modes.

A color that works well in Light Mode, though, might have insufficient contrast in Dark Mode, and vice versa.

Even when colors seem to you like they're going to work well in both modes, it's always best to check your colors with an online color contrast calculator. Now, because tint colors can be dynamic, you can have two slightly different colors for Light and Dark Modes, and when you're picking those colors, aim for a contrast ratio of 4.5 to 1 or higher.

Strong color contrast improves the accessibility and usability of your apps. The system palette should basically have you covered for most of your needs. But, of course, you're going to have to define your own colors as well. Perhaps you have user-selectable label colors or status indicators. As with tint colors, any color can be dynamic.

Given that the perception of color is influenced by the background that it's shown against, you'll want to make some adjustments to help keep those color values looking similar between modes or to make sure that there's enough contrast in both modes.

Now, all this time I've been talking about Light and Dark Modes, and as you may know, that's a little bit of an oversimplification. There's actually two sets of background colors that are called "base" and "elevated." As the names imply, these background colors are about layering interfaces.

When two light interfaces are layered, a simple, diffuse drop shadow is all you need to create visual separation between the two. With dark interfaces, drop shadows are slightly less effective.

System background colors will use the darker or base values for background apps or interfaces and the lighter, elevated values for apps or interfaces that are in the foreground. So take, for example, the Contacts app. It's using the base set of color values when drawn on its own, but when the same interface is brought up in a modal presentation in the phone app, it uses the elevated background colors.

Okay, let's look at a slightly more complicated example. Here's Mail running on an iPad. On its own, Mail is drawn using the base set of background colors.

When we bring in Contacts in a slide-over, we see that it's being drawn with the elevated set of background colors. Now, the lighter appearance of contacts helps it stand out from Mail and advances it into the foreground. When Contacts is displayed side by side in multitasking with Mail, they are both drawn with the elevated set of background colors. This helps provide contrast with that splitter down the middle and keeps the two apps from blending together. When we compose an email in Mail, it comes up in a sheet. This too is drawn with the elevated background colors, but the main app UI Mail looks a little bit darker because modal presentations draw an overlay layer to dim their background content and they cast a little bit of a drop shadow. Now, because background colors change when your app is elevated, you have to be mindful that some of the darker colors that you might use, even from the system palette, may not contrast well. You always have to check your designs when they're in elevated state.

Again, semi-opaque fill and separator colors are going to be your best friends here. They adapt gracefully between base and elevated backgrounds.

Okay, moving on to materials.

Materials have been overhauled and refined with iOS 13. There are now four materials for you to choose from with a range of translucency levels: thick, regular, thin, and ultra-thin.

These materials have been designed to work well against a variety of background contexts.

Their appearance will change dynamically based on whether someone is using your app in Light or Dark Mode. You can select which material you want based on how much separation you want from the background, how much is most appropriate.

The default material is regular, and it's going to work well in most circumstances. But if you're presenting content against this material that needs a little bit more contrast, you can use the thicker material.

For lighter-weight interactions, maybe with simpler content, thin and ultra-thin might be the right way to go. Which material is right for your app just really depends on the content that's being displayed inside of it. Speaking of which, light and dark materials have an accompanying set of vibrancy values for labels, fills, and separator colors. Vibrancy is a visual affect that's used throughout iOS and other Apple platforms. With system materials, it's typically best to use vibrancy rather than solid colors. Because depending on the background context, solid colors can get really muddy and can lead to some serious legibility issues.

Vibrancy helps to maintain that contrast regardless of what's in the background.

The updated visual design system for iOS also includes changes to controls and bars.

Visual attributes like shape and color have been brought into greater alignment for more internal consistency. Controls are now drawn with semantic colors so that they gracefully adapt between Light and Dark Modes.

If you use UIKit controls, you get the benefits of all of this for free.

If you spent time recreating what UIKit gives you for free, with custom controls, you may want to, I don't know how to say this, but stop doing that. Recreating what UIKit gives you for free takes a lot of effort and time, it's hard to do right, and there's very little upside for you.

But of course, custom controls are often necessary. UIKit does not provide everything that you need. For example, UIKit doesn't provide a rating indicator. So, when you're making custom controls, you should use the system palette so that you don't have to do two different color treatments for Light and Dark Mode.

Navigation bars have also been updated. By default, they're now drawn for large titles without the background and shadow.

This allows the title to connect seamlessly with the content that it's labeling. When content scrolls underneath the navigation bar, the background and shadow will fade back in.

Now, large title bars, navigation bars work especially well with this visual treatment, but it can be used for default navigation bars as well. So, in the Settings app, for example, the master view's navigation bar uses a large title and it has no background or shadow.

The standard navigation bar is stylized to match.

Now, while a seamless navigation bar looks great, it's not always going to be appropriate. That background is completely transparent, so if you've tucked anything underneath the navigation bar, it's going to show right through, and it's probably not going to look very good so don't use a treatment then. And if you have a really dense interface with a lot of controls and navigation bar next to the content area, the clear visual delineation that's provided by that shadow can be really helpful.

Okay. So, before we move on, there's one more big feature that I'd like to discuss with you related to Dark Mode. iOS has always provided a handful of symbols for things like table rows and toolbars.

When shown against a dark background, the previous set of symbols did not hold up very well; they often looked a little too thin. So, the design team redesigned all of the symbols in this design system. And what's really cool, as many of you may know already, we're making all of those glyphs available for you to use with SF Symbols.

SF Symbols includes over 1500 symbols.

And this isn't just a new set of glyphs; this represents a completely new way to think about and design glyphs.

As the name suggests, SF Symbols are designed to match the visual design characteristics of San Francisco, the system font for iOS and other Apple platforms.

They can literally be typed out so that they can be displayed inline with text. They have imbedded baseline values to assure proper vertical alignment relative to text. And every SF symbol offers small, medium and large-scale variants relative to the current size for different contexts.

And every symbol comes in nine weights just like the SF font.

Because they're vector based, SF Symbols can scale with text when used with dynamic type. And by offering multiple weights, SF Symbols will become bolder when the bold text accessibility setting is enabled.

Now, when designing comps of your app, you can use the new SF Symbols app to browse or search for symbols, copy the ones that you want to use, go over to your design comp, and just paste them in to a text layer. The updated iOS Apple Design Resources for Sketch is already set up to work with symbols.

To swap out the symbols for this tab bar, for example, you just select the tab bar, go to the inspector, and paste it in to an override for the buttons.

I've been playing with this feature for a few months now, and I have to tell you, it's totally game-changing.

Now, if the set of symbols that we provide, 1500, isn't enough, you can actually generate a template in SVG, go into Illustrator or Sketch and make modifications to design your own and get all the same benefits that I just described. It's really cool.

Okay. Now moving on to modal presentations.

Modal presentations are often called sheets because of the way they slide up over the screen. This animation informs people that they've shifted from one mode to another or into a new modality of your app.

With iOS 13, sheets have a new card-like appearance that's used throughout the system. This style is now the default. And the benefit of this style is that it gives this little peek of what's in the background, which is a helpful reminder that there's a different UI that accommodates a different task or mode of the app that's still in the background. With the full-screen modal sheet, you can sometimes forget what you were doing before. Card-style modal sheets can be dismissed by swiping down anywhere on the screen. And that dismiss gesture is often going to be easier than tapping a button in the navigation bar.

As with swiping to go back, pulling down to dismiss facilitates one-handed operation, which is particularly convenient on devices with larger displays.

Now, you may wonder, "How does this work with scrolling?" When the content area has been scrolled, swiping down will scroll it back to the top. When scrolled all the way back to the top, continuing to swipe will dismiss the modal presentation.

But at any time, you can pull down from the top edge of the card to dismiss.

Now, if this gesture is problematic for any reason, like you have a control in the content area that works with vertical swiping, it can be prevented.

It can also be prevented when there's a mandatory decision that's required in the modal presentation itself. So, for example, here we either need to cancel or add.

And if we pull down, it will just bounce right back. In cases where people must make a decision before leaving a modal context, you can prevent that dismiss gesture and display an action sheet asking people how they wish to proceed, which is actually pretty convenient.

Now, in case you're wondering, all of what I just described here doesn't mean that you don't need to have buttons for modal cards anymore. Buttons are critical for letting people know that they can close the modal. Buttons are also necessary for accessibility reasons. And people might not be familiar with using the gesture yet or don't want to. And when the content area's been scrolled down, tapping a button might actually be more convenient.

Similarly, seeing negative and affirmative action pairs at the top of the screen lets people know what choices they have to act within this modal presentation, what actions they can take.

Now, we think the new card style is pretty great, which is why it's now the default for iOS.

But they're not always appropriate. For some tasks, like editing a picture or marking up a screenshot, you really want to maximize screen space and minimize visual distraction. For workflows like this, you should use the optional full-screen presentation.

And one final comment about modal presentations: modals are for switching modes. Don't use them just because you like the animation or the visual style of them.

So, a good example of modal sheet use is from Calendar. Calendar has two primary modes: viewing events in a grid or list and then creating or editing events.

Viewing your calendar involves scanning all the events that are in your calendar and then selecting them to see detail. Since we're still in the viewing mode, a child view is used for displaying those details. As the name suggests, a child is an extension of the parent view. A child view should be a continuation of the task or workflow that was started in that parent view.

When creating or editing an event, a modal sheet signals to the people who are using Calendar that they've switched into a distinct and new workflow. Okay. Now for our final iOS design topic, and that's contextual menus. With the introduction of 3D Touch a few years ago came a new interaction called Peek and Pop. Peek and Pop was primarily about getting a larger preview of content.

If available, actions could be accessed by swiping that preview upwards.

Contextual menu shifts things around a bit and puts the focus on actions.

Actions are presented immediately. Contextual menus also work on all devices.

Peek and Pop only worked with 3D Touch, so it wasn't available on any iPads and some iPhones. While 3D Touch makes contextual menus appear more quickly, the gesture to get a contextual menu is just tap and hold, and you can do that on any touch device.

Contextual menus are comprised of two parts: there's a menu of commands that can be performed on an item or selection, and an optional preview of the selected item that'll be affected.

That preview can be a helpful reminder of what item will be affected by those menu of commands.

The exact appearance of contextual menus will change based on device size and orientation. On iPhone, the preview and phone are stacked, in portrait, and the same thing on iPad when there's three commands or fewer. Otherwise, the menu and preview are displayed side by side. Contextual menus will appear directly above the object they affect or as close to it as possible.

As with macOS contextual menus, you can choose the order of menu commands. It's best to put the most frequently used or accessed commands at the top so that they're easier to access. Otherwise, you should group commands because they're heavily related with each other. So, it totally makes sense that cut, copy, and paste are near each other.

You can also use separators to create visually distinct groups. And iOS contextual menus can be hierarchical, meaning that some of these options can lead to a secondary submenu.

Contextual menus on iOS also include glyphs to help people find what they're looking for more quickly, and they allow you to warn people about destructive actions by labeling them in red. You should try to add contextual menus to every object in your app.

Think about macOS. You expect every object in every app to have a contextual menu. They're great way to learn what actions can be performed on an object.

And the more iOS apps add contextual menus, the more people will expect every app to support contextual menus, including yours.

Okay, one final comment about contextual menus. The actions they contain should still be available somewhere else in your main interface. Contextual menus are powerful and convenient, but people might not always think to access them. Now, I can't wait to see what you do with Dark Mode, updated modal presentations and the new contextual menu. For more information and resources, go to developer.apple.com/design. There you can find the updated SF font, the SF Symbols app, and the updated iOS Design Resources for Sketch. The Adobe Photoshop and Adobe XD resources will be coming later this summer. Also, check out the Apple Human Interface Guidelines for more details about everything that I covered today.

Okay. Thank you for your time. [ Applause ]

-