-

Modern Swift API Design

Every programming language has a set of conventions that people come to expect. Learn about the patterns that are common to Swift API design, with examples from new APIs like SwiftUI, Combine, and RealityKit. Whether you're developing an app as part of a team, or you're publishing a library for others to use, find out how to use new features of Swift to ensure clarity and correct use of your APIs.

Resources

Related Videos

WWDC21

WWDC19

-

Search this video…

Hi, everybody.

I'm Ben. And together with my colleague Doug, we're going to talk to you about API design in Swift.

So, with the introduction of both binary and module stability we're really excited that for the first time we can introduce frameworks that make full use of Swift to provide rich, efficient, and easy to use APIs as part of Apple's SDK. Now, we've learned a few things as part of designing these APIs that we want to talk to you about today. So, we're going to cover a couple of fundamental concepts and understand how they affect your API designs. And then we're going to take a deep dive into some of the new features in Swift 5.1 and see how they can help you make your APIs more expressive.

Along the way we're going to show you some examples from some of our latest Swift frameworks, including SwiftUI and RealityKit.

Now, we talked about API design before. In particular, in 2016, when we introduced the Swift API Design Guidelines.

And these were available on the Swift.org website. And they contain some really useful advice around how to name and document your API. But I'm not going to recap here except to say that if there's one message they're trying to achieve, it's this: Clarity at the point of use is your most important goal as an API designer. You want to make it so that when you read code using your API it's obvious what it's doing.

And you want to make it easy for your API to be used correctly.

And good naming and readability is a critical part of this.

And there's one new thing around naming that we want to talk about, which is that going forward, we're not going to be using prefixes in the Swift types in our Swift-only APIs. Now, this really helps give these APIs a much cleaner, more readable feel. Now, in C and Objective-C, we had to use prefixes because every symbol was in the global name space with no good way to disambiguate.

And for that reason, both Apple and developers had to stick to a really strict prefixing convention.

And for consistency, we're going to keep using prefixes on the Swift versions of APIs that also have an equivalent in Objective-C.

But Swift's module system does allow for disambiguation by prepending the module name in front of the type. And for this reason, the standard library has never had prefixes. And many of you have found that you could drop them from your Swift frameworks, too.

And bear in mind that you do still have to be a little bit careful even then.

A very general name will cause your users to have to manually disambiguate in the case of conflicts.

And always remember clarity at the point of use.

A general name from a specific framework can look a little bit confusing when you see it out of context. Now, we're going to talk about a couple of topics: Values and references and protocols and generics. And then we're going to cover our two new features, key path member lookup and property wrappers.

So let's start by talking a bit about values and references. First a very quick recap. Swift has three basic concepts for creating a type: Classes, Structs, and Enums.

Classes are reference types. And that means when you have a variable, it just refers to the object that actually holds the values.

And when you copy it, you're just copying that reference. And that means that when you change a value through the reference, you're changing the same object to which both variables refer.

And so they both see the change. Structs and Enums, on the other hand, are value types. And when you copy them, they copy their entire contents. And that means that when you make a change, you're just changing that one copy.

Now, using value types in your API can bring a lot of benefits in terms of clarity at the point of use. If you know you're getting a fresh, unique copy every time, then you don't need to worry about where the value came from and whether somebody has a reference to it still where they might change it behind your back.

You don't need, for example, to make a defensive copy. Now, given this, a common question comes up, which is: Should I be using a reference or a value type in my particular piece of code? And every use case is different. So there are no hard rules here. But here's some general guidance, which is that in general, you should prefer using Structs over classes unless you have a good reason for using a class.

If you default to using a class whenever you create a type, try flipping that default in your code going forward and see how you get on.

Now, classes still play a critical role in Swift. They're essential if you need to manage resources through reference counting. Though often you'll want to wrap that class inside a struct, as we'll see shortly.

They're also a useful construct if something is fundamentally stored and shared.

And importantly, if your type has identity. And that notion of identity is separate from its value.

That's often a sign that a class might make sense.

Now, a good place where we had to make this decision was in RealityKit.

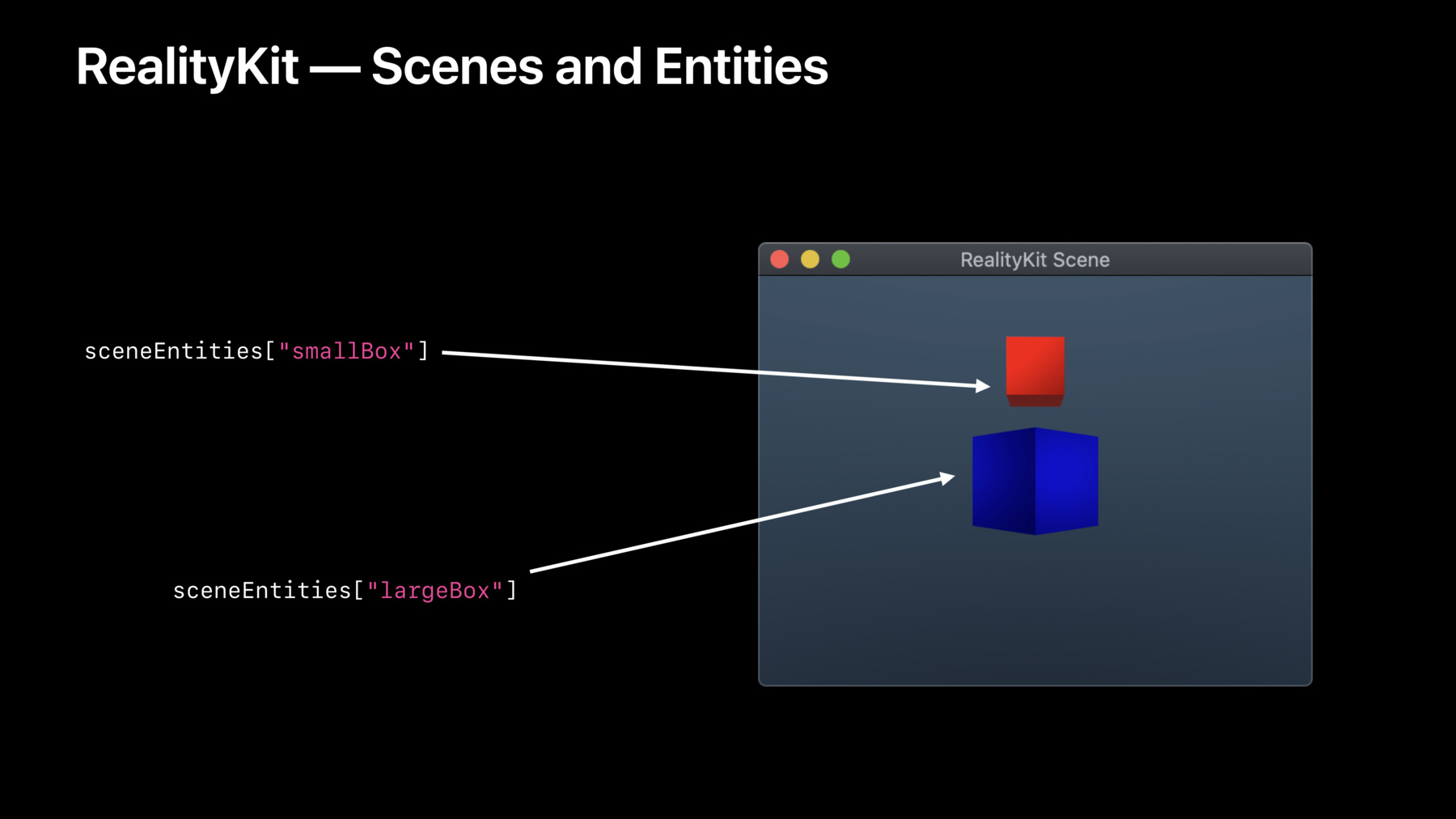

RealityKit's API revolves around these things called entities.

And these represent objects that appear in scenes. And they are stored centrally inside RealityKit's engine. And they have identity.

And when you manipulate a scene by changing an object's appearance or moving them around, then you're manipulating objects directly in that engine. You can think of the reference types as like handles into the actual object stored within RealityKit. So this is a perfect use for a reference type.

But the attributes of those entities, such as their location or orientation in a scene, those are modeled as value types.

Now, let's have a look at how this looks in code.

So let's say we want to create this scene here.

So, we would first create a material type. And then we'd create two boxes out of it. And then we need to anchor them within the scene.

And then, once we've done this, we can manipulate the scene directly using code so we can move the smaller box up along the y-axis. Or rotate the larger box by 45 degrees. And as we're performing these operations on these reference types, we're directly manipulating the scene. And this feels fairly intuitive.

Now, supposing then want to do what we've got here, which is to make one of the boxes a different color. One way we might do that is by changing the material color to be red.

Now, what do I expect, as a user of this API, to happen at this point? Should both boxes change because I've changed the variable they were both created out of? Or should only the subsequent box that I create make use of this new change? That is, should material act like a reference type or a value type? And either model would be a reasonable design for an API. The benefit of using value types for this, though, is that if there's a long distance in your code between when you first created and used the material type and when you change it, then you might forget that you had used it previously. And you might end up changing a part of the scene that you didn't expect.

And so for that reason, RealityKit does choose to make material a value type.

But reference semantics also make sense for other APIs like we've seen with entities.

What's important is that your API has an easy to explain model for how things behave and why.

And most importantly, how that behavior works should not be driven by incidental implementation details of the types. But instead should be a conscious choice based on the use cases.

So, what do I mean by an accidental implementation detail? Well, let's have a look at an example type. Let's say a material type. And I want it to act like a value, so I make it a struct. And I give it a couple of simple properties such as roughness. And then I give it a texture property. And let's say that that texture property needs to manage resources with reference counting. So I decide to make it a class.

Now, we said a moment ago that when you make a copy of a value type, you copy all of its stored properties.

But that when you copy a reference type, you're just copying that reference.

And so when you make a copy of this material type, what will end up happening is that they make a copy of the reference. And so the two types end up sharing the same texture object.

Now, whether that's okay or not really depends on the implementation of texture. If textures are immutable, then it's perfectly fine. In fact, it's pretty desirable from a sharing perspective.

But if texture were fundamentally a mutable type, then what I've created here is actually slightly strange. It behaves neither like a reference, nor a value. I can make changes to properties on the struct.

And it just affects one of the variables. But if I make changes through the texture reference to the object, then it affects both variables. And this can be really surprising for users of your API. And probably more confusing than if you had just stuck with reference semantics all the way through.

And so here we need to make a really key distinction between value and reference types, Structs versus classes, and value and reference semantics, how the type behaves.

Just because something is a value type, like a struct, doesn't necessarily meant that you automatically get value behavior from it. One way that you might not, not the only way, but a common way, is if you include a mutable reference type as part of its public API. So the first question if you wanted something to behave like a value is: Are any of the reference it exposes mutable? And bear in mind, this isn't always obvious.

If we were dealing with a non-final class, then what you might actually have is a mutable subclass. Luckily there are lots of techniques we have to avoid problems like this.

So the easiest one is to do what we've always done with reference types, which is to make a defensive copy. So we could switch our texture stored property to be private.

And then instead have a computed property. And inside the setter, we just make a copy of the texture object. And this avoids the mutable subclass problem.

But, it doesn't solve the problem if texture is fundamentally a mutable type because you could still mutate it just through the getter property. That's how references work.

And so let's consider another option, which is to not expose the reference type at all. And instead, to just expose the properties we want on the object as computed properties on our material value type.

So, we can create a computed property. And in the getter, we just forward on to the relevant property of the object.

But in the setter, we can first check if the object is known to be uniquely referenced. And if it's not, at that point we can make a full copy of the texture object before going on and making our mutation.

By adding this one line to check for uniqueness, we've implemented full copy-on-write value semantics while still exposing the properties we want on our reference type.

So next, let's talk a bit about protocols and generics.

So, we've seen how value types can add clarity at the point of use to your API.

But, value types aren't new. We've had types like CGPoint or CGrect in Objective-C all along.

So what's different? Well, what's different in Swift is the ability to apply protocols to Structs and Enums as well as just classes. And that means you can share code across a variety of types using generics.

And so if you feel you need to share some code between different types, don't feel like you have to create a class hierarchy with a base class that has that shared functionality.

Instead, as the saying goes, in Swift, start with a protocol.

But, that doesn't mean that when you open up XCode and you've got an empty source file you type the keyword "protocol" as your first thing.

In Swift API design, like any Swift design, first explore the use case with concrete types. And understand what code it is that you want to share when you find yourself repeating multiple functions on different types.

And then factor that shared code out using generics.

Now, that might mean creating new protocols. But first, consider composing what you need out of existing protocols. And when you're designing protocols, make sure that they are composable.

And as an alternative to creating a protocol, consider creating a generic type instead.

So let's have a look at some examples that show some of these different things.

So, let's say I wanted to create a geometry API. And as part of that, I wanted to create operations on geometric vectors. I might start off by creating a protocol for a geometric vector. And I could give it the operations that I want to define, like dot product or the distance between two vectors.

Now, I need to store the dimensions of the vector. So I might make my geometric vector refine the SIMD protocol. If you're not already familiar with SIMD types, they're basically like kind of homogenous tuples that can very efficiently perform calculations on every element at once.

And they've got a lot great new features in Swift 5.1. And they're perfect for doing geometry calculations. So, we're going to store our dimensions in that base SIMD type. And we'll also want to constrain it to only work on scalar SIMDs so that we can do the calculations we want. Now, once we've defined this protocol, we could then go and implement default implementations for all of the operations we want to do on vectors.

And then we want to give a conformance to this protocol to each of the types that we want to get these new capabilities.

And this three-step process of defining the protocol, giving it a default implementation, and then adding a conformance to multiple types, it's actually kind of tedious. And it's worth taking a step back for a second and saying: Was the protocol really necessary? The fact that none of these conformances actually have their own custom implementation is actually kind of a warning sign that maybe the protocol isn't useful. There's no per type customization going on. And in fact, this operation works on every different kind of SIMD type.

So, is the protocol really giving us anything? If we take a step back, and instead of writing our default implementation on our new protocol, we just write it as an extension directly on the SIMD protocol with the same constraints, then we're done. In this single page of code we've automatically given all of the capabilities we need to all of the SIMD types that contain floats.

It might feel tempting sometimes to create this elaborate hierarchy of protocols and to classify the different types into this hierarchy. But this sort of type zoology, which it feels satisfying, isn't always necessary.

And there's also a practical consideration here.

This simpler extension-based approach without the protocol is a lot easier for the compiler to process.

And your binary sites will be smaller without a bunch of unnecessary protocol witness tables in it.

In fact, we've found that on very large projects, with a large number of complex protocol types, we could significantly improve the compile time of those applications by taking this simplification approach and reducing the number of protocols.

Now, this extension approach is good for a small number of helpers. But it does hit a scalability problem when you're designing a fuller API. Earlier when we're thinking about creating a protocol, we said that we'd define geometric vector and make it refine SIMD, which we'd use for our storage.

But is that really right? Is this an Is-a relationship? Can we really say a geometric vector "is a" SIMD type? I mean, some operations make sense. You can add and subtract vectors.

But others don't. You can't multiply two vectors by each other. Or add the number 1 to a vector. But these operations are available on all SIMD types. And have other definitions that do make sense in other contexts. Just not in the context of geometry.

And so if we were designing an API that would be easy to use, then we might consider another option, which is instead of an Is-a relationship to implement as a has-a relationship. That is, to wrap a SIMD value inside a generic struct.

So we could create instead a struct of geometric vector. And we make it generic over our SIMD storage type so that it can handle any floating point type and any different number of dimensions.

And then once we've done this, we have much more fine-grained control over exactly what API we expose on our new type.

So we can define addition of two vectors to each other. But not addition of a single number to a vector. Or we can define multiplication of a vector by a scaling factor, but not multiplication of two vectors by each other.

And we can still use generic extensions. So our implementations of dot product and distance remain pretty much the same as they did before.

Now, we've actually used this technique within the standard library. For example, we just have one SIMD protocol. And then we have Structs that are generic that represent each of the different sizes of SIMD type. Notice that there's no SIMD2 or SIMD3 protocol here. They wouldn't necessarily add much value.

Users can still write generic code for a specific size of SIMD by extending, say, the SIMD3 type with the cross product operation you would only want to define on three-dimensional SIMD types.

So hopefully this gives you a feel for how generic types can be just as powerful and extensible as protocols can be.

Now, we're still using the power of protocols here.

We have our floating point protocol constraining the scalar type on the generic SIMD that gives us the building blocks that we need to write this code. Now, we could write this same cross product operation on our geometric vector type.

But when we do, the implementation looks a little bit ugly. Because we keep having to indirect through the value storage in order to get at the x, y, and z coordinates. And so it would be nice if we could clean this up. Now, obviously we could just write computed properties on our vector type for x, y, and z. But there's actually a new feature in Swift 5.1 called Key Path Member Lookup that allows you to write a single subscript operation that exposes multiple different computed properties on a type all in one go. And so we could use this if we chose to, if it made sense, to expose all of the properties on SIMD on our geometric vector all in one swoop. Let's have a look at how we'd do that.

So first we tag our geometric vector type with the dynamic member lookup attribute.

And then next, the compiler will prompt us to write a special dynamic member subscript.

And this subscript takes a key path. And the effect of implementing this subscript is that any property that is accessible via that key path automatically is exposed as a computed property on our geometric vector type. So in our case, we want to take a key path into the SIMD storage type and have it return a scalar. And then we just use that key path to forward on and retrieve the value from our value storage and return it. And once we've done this, automatically our geometric vector gets all of the properties that SIMD has.

So for example, it gets the x, y, and z coordinates. And they even appear in autocompletion in Xcode.

And if you tried this feature in Swift 5 when it was string-based, the difference here is that this version is completely type safe.

And a lot more of it is done at compile time. Now that we have access to the x, y, and z properties, we can clean up the implementation of our cross product operation quite a bit. There, that's much nicer. Now, this dynamic member capability is not just useful for forwarding onto properties. You can also put complex logic into the subscript. So, let's look at one more example.

Let's go back to our example from earlier where we exposed a specific property from texture with copy on write value semantics. Now, this works for one property. But it would be unfortunate if we had to write this same code every single time.

What if it wanted to expose all of the properties on texture as properties on our material type with copy-on-write semantics? Well, we can do it with dynamic member lookup.

So first we add to the dynamic member attribute to our type.

And then we implement the subscript operation. And we're going to make it take a writable key path because we want to be able to both get and set the properties.

And we're going to make it generic on the return type because we want to get any different type out of the texture.

And then we implement the getter and setter. In the getter, we just forward on like we did before.

But in the setter, before we do our mutation, we add the unique referencing check and full copy of texture.

And by doing this, in one subscript method that's not too long, we expose every single property on texture with full copy-on-write semantics on our material type.

And this is a really useful way to get value semantics out of your types.

This new feature has lots of different applications. And it actually composes really well with a new feature in 5.1 called Property Wrappers that Doug is going to you about next. Doug.

Thank you, Ben.

So, Swift is designed for clear concise code and to build expressive APIs, right? It's also there for code reuse. We've been talking about generics and protocols. And they're there so you can create generic code, so for your functions, for your types, that can be reused. So property wrappers is a new feature in Swift 5.1.

And the idea behind property wrappers is to effectively get code reuse out of the computed properties you write.

Things like this large pile of code here.

And what is going on here? So, all we tried to do was expose a public property, right? And here we have it. We just want an image property that's public. But we don't want all of our users, our clients, to be able to go and write whatever value in there. We want to describe some policy. So it's a computed property. And our actual storage is back here in this internal image storage property.

All the access to that storage is gated through the getters and setters.

This is a lot of code. You've had a few seconds with it. Some of you have probably recognized what this is.

It's a really long-winded way to say this is just a lazy variable image.

Now, this is so much better.

It's one line of code instead of two properties with a mess of sort of policy logic for accessing. And we have this nice modifier "lazy" there to tell you here's what the actual semantics are.

This is important. It's better documenting. It's easier to read.

That's why "lazy" has been in the language since Swift 1.

Now, the problem is, this is one instance of a more general problem. So, let's take a look at another example here, the code structure.

Basically identical.

But the policy, what's actually implemented here in the getter and setter, is different. So if you're looking through the logic here, you see this is sort of a late initialization pattern. You have to set this thing once, or initialize it once before you can read it. Otherwise you get a failure. This is a fairly common thing.

This kind of code shows up in a lot of places. We couldn't go and extend Swift with another language feature that attacks this one problem.

But really, we want to solve this more generally, because we want people to be able to build libraries of these things, where they have the notion of separating the policy for accessing a value out.

And so this is the idea behind property wrappers, to eliminate this boilerplate and get more expressive APIs.

So, they look a little like this.

And the idea here is we want to capture the notion of you're declaring a property. So here it is this public text variable, and applying the late initialized property wrapper to give it a particular set of semantics, to give it a particular policy.

Now, this at-LateInitialized, this is a custom attribute. It's a new notion that we're using a bit in Swift. And essentially, it's saying: Apply this late initialized pattern, whatever it is. We'll get back to that in a moment.

But just from the code perspective, this is a whole lot like lazy. And it's giving us all the same benefits as lazy.

We've gotten rid of all that boilerplate.

But also we've documented at the point where we declare this thing, what are the actual semantics. This is far easier to read and reason about than that mess of code.

All right. Enough talking about this one little line of code. Let's see what LateInitialized actually looks like.

And what you'll see here it's a bit of code. But it's the same code we just saw. It's the same policy pattern behind late initialization.

You've got the getter and setter here. The set is just updating the storage. The getter is checking to make sure we've set it at least once, and then returning the value when we have.

Fairly direct.

Now, what makes this simple generic type interesting is that it is a property wrapper. It's indicated as such by the property wrapper attribute here at the top.

Now, what that's doing is it's enabling the custom attribute syntax to say we can apply this thing to some other property.

Now, with the property wrapper attribute come a couple of requirements. The main one is to have this value property.

This is where all the policy is implemented. So all accesses to a late initialized property go through here.

And we can see that the actual notation is finding some extracted notion of what late initialized is.

The other interesting thing in this particular example is that we've declared an initializer that takes no parameters.

Now, this is optional with the property wrapper. But when you have it there, what it's saying is that properties that are applying this wrapper get implicit initialization for free going through this particular initializer.

Okay.

Let's actually use this thing. So, when you use a property wrapper by applying it to a particular property, the compiler is going to translate that code into two separate properties. We're essentially expanding out into that pattern we saw in the beginning here.

So you have the backing storage property with this $ prefix. So $text. And the type of this is an instance of the property wrapper type. So now we have a late initialized string.

That's providing the storage.

It's going to be initialized implicitly by the compiler by calling that no parameter initializer that we just talked about. Because it's there, now we get implicit initialization. And late initialize is free to do whatever it wants. As you might recall, it set the storage to nil.

The other thing that the compiler is doing here is it's translating text into a computed property.

And so the getter it's going to create is accessing $text. And then retrieving the value out of $text by calling the getter for value. And we do the same thing for the setter, writing the new value into $text.value. And so this is what allows your property wrapper type to have its own storage, however it wants to store it, either locally or somewhere else.

And then enforce whatever policy you should have about accessing that data through the getter and setter value.

So overall, this is really nice. We've teased apart the policy, put it in one place in the late initialized wrapper from the application of that policy, which we can do on any number of different properties of whatever types we want, making it far simpler and having less boilerplate.

So, let's take a look at another example.

Ben was talking a bit about value and reference semantics.

Now, when you're dealing with reference semantics and mutable state, you're going to find yourself doing defensive copying at some point.

Of course, we could manually do that wherever we need it. But why not go and build a property wrapper for it? So, here the property wrapper, the shape of it, is basically the same as we've seen before. It had some kind of storage. And it has a value property. All of the policy for this property wrapper is here in the setter. When we get a new value, go ahead and copy the value. And since we're using NSCopying to do our copies, it just goes ahead and calls that copy method and does the cast.

The other interesting thing with defensive copying is it provides an initial value initializer.

This is like that no-parameter initializer. You don't have to have it in your property wrapper. But when it's there, it lets you provide a default value on any property that's wrapped with this property wrapper. That default gets fed into this initializer. And we can enforce whatever policy we want on initialization.

In our case, it's the same as the set policy. We want to go ahead and create a copy defensively and assign that a result then.

Let's take a look. So, if we go define some defensive copying UIBezierPath.

What's going to happen? Well, the compiler is going to translate this into the two different definitions. We're going to have an initializer here first.

So here, whenever we create this path, it has a default of the UIBezierPath. Just an empty instance that's created. And then when we go ahead and explode this out into multiple properties, there's the backing stored property, $path.

And notice how we're initializing it. We're feeding the initial value that the user gave into the initial value initializer so it can be defensively copied.

The getter and setter look exactly the same. We're just going through $path.value for both get and set.

Now, this is of course the right semantics by default. Defensive copying should go ahead and copy.

In this case, well we know something about our default value. It's creating a new object. Why would we go and copy that thing? So, let's optimize this a little bit just because we can.

So we can extend defensive copying. It's just a type. There's nothing magical about this type other than the fact that it's behaving like a property wrapper when used that way. And so we can give it this withoutCopying initializer.

When we want to use that, we can go ahead and write an initializer for our type.

And what we're doing here is we're assigning to $path to call the defensive withoutCopying initializer so we can avoid that extra copy.

So there's really nothing more magic that's going on here. $path is just a stored property. It's only magical in the sense that the compiler generated it for you as part of applying this property wrapper pattern. But you can go and treat it like a normal variable whenever you want, including setting up your own initialization.

Now, this is a little bit boilerplatey, still. It's unfortunate that we had to write that initializer. So there's one other initialization form that you might see.

And that is that when you are declaring the customer attribute, so at-DefensiveCopying, you can actually initialize right there in the properties declaration with whatever you want. So here we can go and call the withoutCopying initializer to initialize the backing storage property with exactly what we want. It's one nice little declaration. And you get the benefits of getting the default in the memorize initializers for free, still.

All right.

So, property wrappers are actually fairly powerful. They abstract away this notion of policy to access your data. So you can decide how your data is stored. And you can decide how your data is accessed. And all your users need to do with your property wrapper is use that custom attribute syntax to tie into your system. So as we've been developing property wrappers, we've found a lot of different uses for them all around this sort of general notion of data access.

So for example, you may have seen the user defaults example. And here's where we're setting up a relationship between a well-typed property here in Swift that you just referred to as a Bool and some stringly-typed entity. So we describe in the construction arguments exactly how to go ahead and access that thing. And all of the logic for dealing with user defaults, that's over in this user default property wrapper.

So we built thread-specific. If you want thread local storage.

You can apply the thread-specific property wrapper. All the details of dealing with the system's thread-specific storage are there in the property wrapper once. You can just think of this thing like a local memory pool.

And also, from the Swift community, as we've been building this feature, we found that this actually works really well for describing command line arguments. If you're building a command line tool with a library out there that uses this kind of shorthand syntax, just say, well, I want a minimum value. Here's how I describe the option.

Here's the strings that the user passes, where they're short, what the documentation is. All the extra stuff that you need to very, very succinctly declare your command line options.

There's a ton of really cool stuff that we can do with property wrappers because we have this nice, clean syntax for factoring stuff out.

Now, as you probably noticed from another session, we use property wrappers extensively throughout SwiftUI to describe the data dependencies of your view.

And there's several of these different property wrappers that exist within Swift UI. So here we have State for introducing view local state. We have Binding for a sort of first class reference out to state that's somewhere else. You've probably seen Environment, an environment object.

All of these things are property wrappers. And the really nice thing about describing them that way in Swift is that you're stating your policy for where this data is and how it's accessed in one place in the declaration.

But when you go and build your view, you don't care about that. You don't care where the data is. It's managed by the system for you.

You just can refer to the particular slide I'm on in my keynote deck.

Pull out its number. If you want to go and edit something, you can use $ and get back at the actual binding.

So, all of the logic for dealing with the data and watching for change updates and maybe even storing the data on the side, that's all handled off in the policy in the property wrapper types. You don't have to think about it. You just worry about working with your actual data.

Now, there's one thing that's a little bit interesting on this slide.

So, there's $slide.title.

We're passing down so we can edit the slide title in a text field.

$slide -- well, we've seen that before. That's the backing storage property. That's what the compiler is synthesizing on our behalf because we applied the binding property wrapper here.

But that's a binding. It doesn't have a title.

Title is something that's part of my data model. I have a slide data model. What gives? So, this is actually a combination of both property wrappers and the key path member lookup feature that Ben talked about earlier.

And so, let's actually focus in on binding, the thing that's in Swift UI and provides this first class reference. First and foremost, binding is a property wrapper. So, it has the standard value. It's parameterized over any type because you can have a binding to anything. It has whatever the access pattern is. It doesn't matter. We don't know what it is because it's handled by the framework for us. But, binding also supports key path member lookup with this generic subscript.

These generic subscripts are kind of a mouthful. And we don't have to know what the implementation is, but we should look at the type signature a little more closely because it is interesting. So, what we're taking in is a key path. It's rooted at our particular value type. So the thing that we're binding, like a slide, and accessing any property within that particular entity.

Now, returning is not a value that's referring to like something in there. We're returning a new binding that is focused in on just one particular property of the outer binding, still maintaining that data dependency there.

So, how does this work in practice. Well, we had our slide, which is a binding into one of our slide types.

And primarily we think about this as the value. So we can refer to slide, we get an instance of slide. We can refer to slide.title and get an instance of that string. All the while tracking modifications behind the scenes.

If we enter $Slide, well, we get that binding instance to the slide.

When we enter $slide.title, well now we're looking for a property that's not there on binding, so the compiler's rewriting this into a use of the dynamic number subscript, passing in a key path to slide.title.

The way this is resolved is one of these focused bindings pointing into the string property within the previous binding following all the data dependencies throughout.

And so, if we step away from the language mechanism that we've been focusing on and sort of look at the high level code that we did here, it's really nice. We established our data dependency using this custom attribute in the property wrapper.

We have primary access to our data very easily to go read it or modify it. And if we want a pass down a first class reference through our binding, we put this prefix of $ at the front of it. And the effect we get is we always get to pass down a binding to some other view.

So, we've talked about a couple of different topics. We talked about value semantics and reference semantics, when to use each of them and how to make them work together.

We've talked about the use of generics and protocols.

And remember, protocols are extremely powerful. But use them for code reuse. That's what they're there for. Not for classification and building big hierarchies because those are going to get in your way. You're not going to need it. And finally, we went into a little deep dive into the property wrappers language feature and how we can use it to abstract access to data.

All right. Thank you very much.

Come see us in the labs if you'd like to chat about any of these.

[ Applause ]

-