-

Measuring Performance Using Logging

Learn how to use signposts and logging to measure performance. Understand how the Points of Interest instrument can be used to examine logged data. Get an introduction into creating and using custom instruments.

Resources

Related Videos

WWDC23

WWDC18

-

Search this video…

Good afternoon.

My name is Shane. I'm with the Darwin Runtime team. And I'd like to welcome you to measuring performance using logging.

So we heard a lot about performance on Monday.

Performance is one of those things that's key to a great user experience. People love it when their games and their apps are fast, dynamic, and responsive.

But software is complex so that means that when your app is trying to do something, sometimes a ton of things can be going on and that means you can find some performance wins in some pretty unlikely places.

But doing so, unearthing those of performance wins requires an understanding, sometimes a deep understanding of what it is your program is doing.

It requires you to know when your code is executing exactly, how long a particular operation is taking.

So this is one place where a good tool can make a real difference.

And we know that building better tools, making them available to you, is one of the ways that we can help you be a more productive developer.

So today I'm going to talk about one of those tools. Today, I'm going to talk about signposts. Signposts are a new member of the OSLog family.

And we're making them available to you in macOS. We're making them available to you in iOs. And you can use them in Swift and in C, but the coolest thing is we've integrated them with Instruments. So that means Instruments can take the data that signposts produce and give you a deep understanding of what it is your program is doing.

So first a little history.

We introduced OSLog a couple of years ago.

It's our modern take on a logging facility. It's our way of getting debugging information out of the system. And it was built with our goals of efficiency and privacy in mind.

Here you can see an example of OSLog code where I've just created a simple log handle and posted a hello world to it.

Signposts extend the OSLog API, but they do it for the performance use case. And that means they are conveying performance related information, and they're integrated with our developer tools and that means you can annotate your code with signposts and then pull up Instruments and see something like this.

So Instruments is showing you this beautiful visualization of a timeline of what your program is doing and the signpost activity there. And then on the bottom there's that table with statistical aggregation and analysis of the signpost data, slicing and dicing to see what your program's behavior is really like.

In this session, I'll talk about adopting signposts into your code and show you some of what they're capable of. And then we're going to demonstrate the new Instrument signpost visualization to give you an idea how signposts and Instruments work together. So let's start.

I'm going to start with a really basic example.

Imagine that this is your app.

And what you're trying to investigate is the amount of time a particular part of the interface takes to refresh. And you know to do that you want to load some images and put them on the screen. So once again, an abstract, simple view of this app might be that you're doing the work to grab an asset. And after you've gotten them all, the interface is refreshed.

What a signpost allows us to do is to mark the beginning and the end of a piece of work and then associate those two points in time, those two log events with each other.

And they do it with an os signpost function call. There are two calls. One with .begin and one with .end. Here I've represented the begin with that arrow with the b underneath it. And I represented the end with the arrow with the e under it. And then we're going to relate those two points to each other to give you a sense of what the elapsed time is for that interval. All right.

In code, there's this simple implementation of that algorithm where for each element in our interface, we're going to fetch that asset and that's the piece of operation that we're interested in measuring.

So to incorporate signpost into this code base, we're going to simply import the module os.signpost that contains that functionality.

And then because signposts are part of the OSLog functionality, we're going to create a log handle. Here, this log handle takes two arguments, a subsystem and a category.

The subsystem is just probably the same throughout your project. It looks a lot like your bundle ID. And it represents the component or the piece of software, maybe the framework that you're working on.

The category is used to relate -- to group related operations together or related signposts. And you'll see why that could be useful later in the session. Once we have that log handle, we're just going to make two calls to os signpost. One with .begin. One with .end. We're going to pass that log handle into those calls. And then for the third argument, we have a signpost name.

The signpost name is a string literal that identifies the interval that identifies the operation that we're interested in measuring.

That string literal is used to match up the begin point that we've annotated or that gets marked up with that os signpost begin called and the end point. So on our timeline, it just looks like this. At the beginning of each piece of work, we've dropped an os signpost. At the end of each piece of work, we've dropped an os signpost. And because those string literals at the begin and end call sites line up with each other, we can match those two together. But what if we're interested in also measuring the entire amount of time the whole operation, that whole refresh took? Well, in our code, we're just going to add another pair of os signpost begin and end calls. Pretty simple. And this time I've given it a different string literal, so a different signpost name. This time refresh panel to indicate that this is a separate interval, separate from the one inside the loop.

In our timeline, we're just marking two additional signposts.

And that matching string literal of refresh panel will let the system know that those two points are associated with each other.

All right.

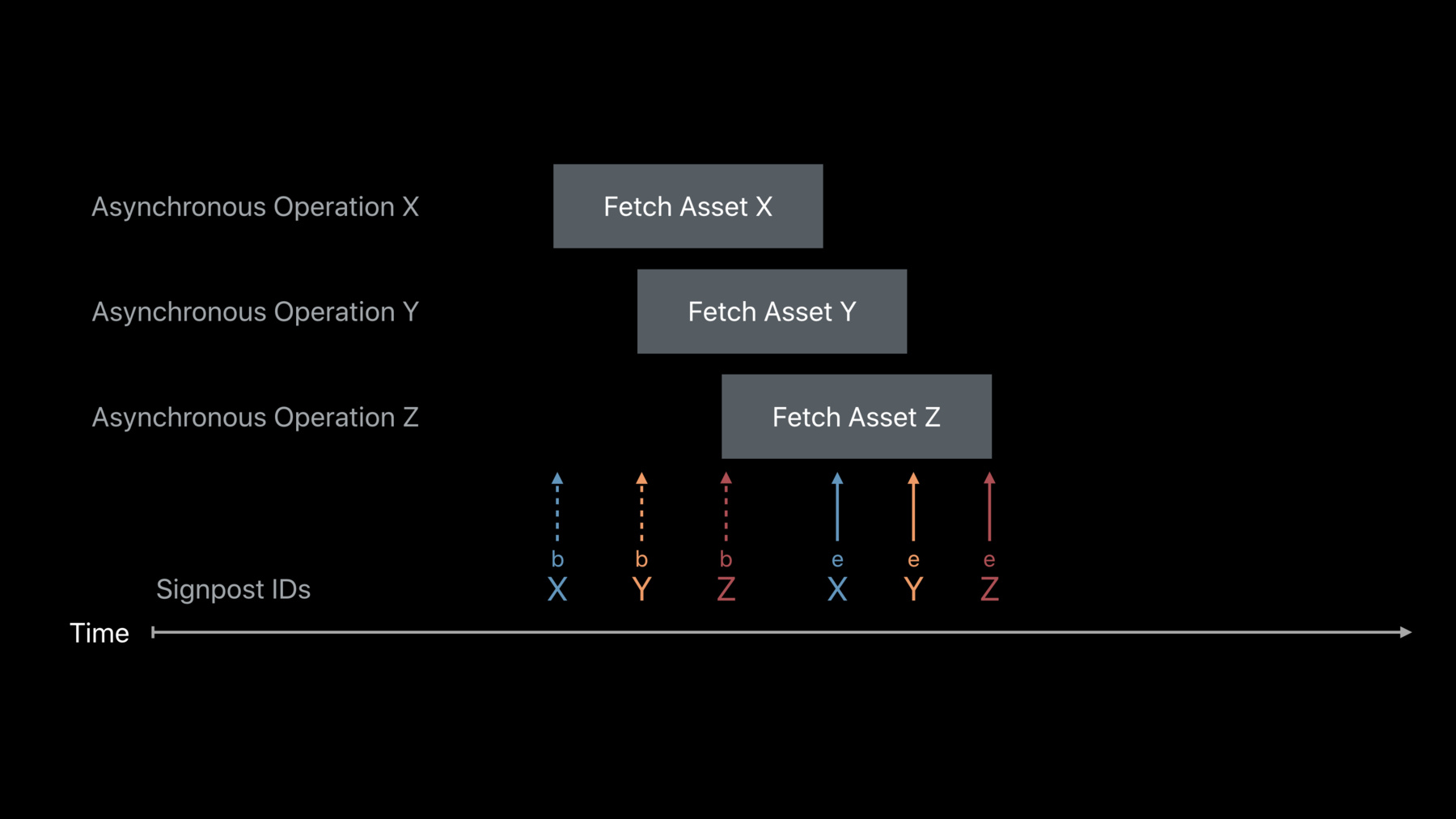

It's not a super simple example. If your program ever does step one and then step two then step three in a sequential fashion then that would work. But in our systems, often we have a lot of work that happens asynchronously. Right. So instead of having step one, step two, step three, we're often kicking things off in sequence, right, and then letting them complete later. So that means that these operations can happen concurrently. They can overlap.

In that case, we need to give some additional piece of information to the system in order for it to tell those signposts apart from each other.

And to do that, so far we've only used that name. Right. That name will match up the end and the beginning point.

So that string literal so far has identified intervals, but it hasn't given us a way to discriminate between overlapping intervals.

To do that, we're going to add another piece of data to our signpost calls called a signpost ID.

The signpost ID will tell the system that these are the same kind of operation but each one is different from each other.

So if two operations overlap but they have different signpost IDs, the system will know that they're two different intervals. As long as you pass the same signpost ID at the begin call site and the end call site, those two signposts will be associated with each other.

You can make signpost IDs with this constructor here that takes a log handle, but you can also make them with an object.

This could be useful if you have some object that represents the work that you're trying to do and the same signpost ID will be generated as long as you use the same instance of that object. So this means you don't have to carry or store the signpost ID around. You can just use the object that's handy.

Visually, you can think of signpost IDs as allowing us to pass a little bit of extra context to each signpost call which can relate the begin and end markers for a particular operation with each other.

And this is important because not only can these operations overlap, but they often take differing amounts of time. Let's see this in our code example.

So here's our code. I'm going to transform that synchronous fetch async call in to an asynchronous one.

So here I'm just going to give it a completion handler. This is a closure that will run after the fetch asset is complete.

And then I've also added a closure, a completion handler for running after all the assets have been fetched.

In each case, I've moved that os signpost end call inside of a closure to indicate that that's when I want that marked period of time to end.

Okay.

So because we think that these intervals will overlap with each other, we're going to create new signpost IDs for each of them. Notice in the top example I've created one with the constructor taking a log handle. And the second one, I've made off that object that is being worked on, the element. And then I simply pass those signpost IDs into the call sites and we're done.

You can think of signpost as being organized as a kind of classification or hierarchy. Right. All these operations are related together by the log handle meaning that log category.

And then for each operation that we're interested in, we've given it a signpost name.

Then because those signposts could overlap with each other, we've given them that signpost ID that tells the system that that's a specific instance of that interval.

This interface was built specifically to be flexible so you control all the arguments into your begin site and your end site. You control that signpost name, the log handle you give it, and the ID. We've done this because as long as you can give the same arguments at the begin site and the end site, those two signposts will get matched with each other. That means your begin and end sites can be in separate functions.

They can be associated with separate objects. They may even live in separate source files.

We've done this because we want you to be able to adopt it into your code base. And so whatever entry and exit conventions you have, you can use these calls. So that's how to measure intervals with signposts. You may want to convey some additional information, some additional performance relevant information along with your signposts. And for that, we have a way to add metadata to signpost calls.

So here's your basic signpost call. To that, we can add an additional string literal parameter.

This allows you to add some context to your begin and end call sites.

Perhaps you have multiple begin and exit points for a particular operation, but the string literal is also an OSLog format string. And that means I can use it to pass additional data into the signpost. So here, for example, I've used that %d to pass in four integers.

But because it's an OSLog format string, I can also use it to pass many arguments of different types. So here I've passed in some floating-point numbers. And I've even used the format specifier to tell the system how much precision I want. You can pass dynamic strings in with the string literal formatter.

And that'll let us pass in information that comes from a function call or comes from a user entered piece of information.

And we reference that format string literal with a fixed amount of storage which means that you can feel free to make it as long and as human readable as you like.

This human readable string is the same one that will be rendered up in the Instruments. So you can feel free to give it some context. I've given it here for the various arguments. And Instruments will be able to show that full rendered string, or it still has programmatic access to the data that's attached.

In addition to metadata for those intervals, you may want to add individual points in time.

That is, in addition to the begin signpost and the end signpost, you may have a signpost that's not tethered to a particular time interval but rather just some fixed moment. And for that, we have an os signpost with the event type.

The os signpost with the event type call looks just like the same as the begin and end, this time with the event type.

And it marks a single point in time.

You could use this within the context of an interval or maybe because you want to track something that's independent of an interval like a user interaction.

So for that fetch asset interval we're talking about, maybe you want to know when you've connected to the service that provides that asset. Or maybe you want to know when you've received a few bytes of it.

You can use this to update the status or progress of a particular interval many times throughout that time of that interval.

Or you might be tracking maybe a triggering event like maybe a user interface interaction like somebody has just swiped to update that interface. Although, if you're really investigating in a performance problem, they might be swiping a lot so this might be what you see instead.

If you have signpost enabled, they're usually on by default, but I'd like to talk about conditionally turning them on and off.

First I'd like to emphasize that we built signpost to be lightweight. That means we've done a lot of work to optimize them at emit time. We've done this through some compiler optimizations that make sure that work is done in front instead of runtime. We've also deferred a lot of our work so that they're done on the Instruments backend. And that means that while signposts are being emitted, they should take very few system resources. We've done this because we want to minimize the impact to whatever your code is running. And we've also done it because we want to make sure that even if you have very small time span, you can emit a lot of signposts to get some fine-grained measurements.

But you may want to be able to turn your signposts off. Maybe you want to eliminate as much overhead as you can from a particular code path. Or you might have two categories of signposts, both of which are super-high volume and you really are only interested in debugging one or the other at a given point in time.

Well, to do that we're going to take advantage of a feature of OSLog, the disabled log handle.

So the disabled log handle is a simple handle. And what it does is every OSLog and os signpost call made against that handle will just turn into something very close to a no-op.

In fact, if you adopt this in C, we'll even do the check for you in line and then we won't even evaluate the rest of the arguments.

So you can just change this handle at runtime. Let me show you an example.

So we're going to go back to the very first example code that we had. And you see that initialization of that log handle up top.

Well, instead I'm going to make that initialization conditional. So I'm either going to assign it to the normal os log constructor or I'm going to assign it to that disabled log handle. If we take the first path, all the os signpost calls will work as I described, but if we take the second path, those os signpost calls will turn into near no-ops.

So as I said before, notice that I didn't have to call any of my call -- I didn't have to change any of my call sites. I only had to change the initialization.

And I made the initialization conditional on an environment variable. This is the kind of thing that you can set up in your Xcode scheme while you're debugging your program.

Now I said you didn't have to change in the call sites, but maybe you have some functionality that is instrumentation specific. That is, it might be expensive but it might only be used for while debugging.

So in that case, you can check a particular log handle to see if signposts are turned on for it with the signposts enabled property. The signposts enabled property can then be used to gate that additional operation.

Okay. So all the examples that I've shown so far have been in Swift, but signposts are also available in C.

All the functionality I've talked about so far is available: the long handles, emitting the three different kinds of signposts, and managing your signpost identifiers.

For those of you who are interested in adopting in C, I encourage you to read the header doc. and header doc covers all this information that I have but from a C developer's perspective.

All right.

Now you've seen how to adopt signposts in your code. And maybe you have a mental model of what they represent. So I would love for you to see how signposts work in concert with Instruments. And for that, I'm going to turn it over for the rest of the session to my colleague, Chad.

Thank you.

All right.

Thank you, Shane.

Now today I want to show you and demonstrate for you three new important features in Instruments 10 to help you work with signpost data.

The first is the new os signpost instrument. And that instrument allows you to record, visualize, and analyze all of the signpost activity in your application.

The next feature is points of interest. I'll talk a little bit about what points of interest are and when you might want to emit one. And then I'm also going to show you the new custom instruments feature and how you can use it with os signposts to get a more, I guess, refined presentation of your signposts.

So let's take a look at that in a demonstration.

Okay.

Now to start with, we're going to take a look at our example application first. And that is our Trailblazer application.

This app is -- shows you the local hiking trails. And it basically downloads these beautiful images for you as we scroll.

Now you'll notice that initially we have a white background and then the image comes in later and fills in. And this is a pretty common pattern in an application like this. And sometimes it's implemented with a future or a promise but this pattern -- as much as it helps with performance, it's also pretty difficult to profile. And the reason for that is because there are a lot of asynchronous activities going on. As the user scrolls, there are downloads that are in-flight at the same time. And if the user scrolls really quickly like this then the download may not complete before the image cell needs to be reused. And so then we have to cancel that download. If we fail to do that, then we end up with several downloads running in parallel that we didn't really want.

So let's take a look at how we can use signposts to analyze the application of our Trailblazer.

Now inside the trail cell, we have a method called startImageDownload. And this is invoked when we need to download that new image, and it's passed in the image name that should be downloaded.

Now we have a download helper class here that we create an instance of an pass in the name and set ourself as the delegate so it'll call us back when it's downloaded. And in this case, since the downloader represents the concurrent activity that's going on, this asynchronous work, it's a great basis for a signpost ID. So we're going to create our signpost ID using our downloader object.

Now to start our signposts, we're going to do an os signpost begin. And we're going to send it to our networking log handle so take a real quick look at our networking log handle. You see we're using our Trailblazer bundle ID and a category of networking.

Now we're going to pass an image or, sorry, a signpost name of background image so that way we can see all of our background image downloads. And it will pass that signpost ID that we created. And we'll attach some metadata to begin to convey the name of the image that we are downloading.

So then we'll start our download, and we'll set our property to track that. We have it currently runningDownloader.

Now when that finishes, we'll get this didReceiveImage callback here. And we'll set our image view to the image that we received.

And we'll call end on the signpost. And we'll use the exact same log handle, the same name, the same signpost ID but this time we're going to attach some end metadata to say finished with size.

And you'll notice here that we've annotated this particular parameter with Xcode colon size-in-bytes. And what this does is it tells Xcode and Instruments that this argument should be treated as a size-in-bytes for both display and analysis.

Now these are called engineering types. And they can be read about in the Instruments developer help guide which is under the help menu in Instruments.

Now once we've completed our downloading, we can set that back to nil. Now there are two ways that we can finish a download. That was the success path. And then we have to consider the cancel path.

So in prepare for reuse, if we currently have a running downloader, we're going to need to first cancel that downloader.

So in that case, we're going to emit an end for the interval, and we're going to use that same logging handle, signpost name, signpost ID. And we're going to use cancelled as the end metadata to separate it from when we finish successfully.

Now that's enough to actually do some profiling. So we're going to go over here to a product profile. And that will start up Instruments once we've finished building and installing. That will start up Instruments here. And we can create a new blank document. Then we can go to the library, and I can show you how to use that new os signpost instrument. So we have our new os signpost instrument here. And we'll just drag and drop that out into the trace. We'll make a little bit of room here for it and then we will press record. And I'll bring our iPhone back up here to the beginning. All right. So now we'll do some scrolling and then we'll also do some really, really quick scrolling. And then we'll let that settle down. Now we can go back to Instruments and see what kind of data we recorded.

So I'm going to stop the recording.

And now you'll notice here that, in the track view, we have a visualization of all of our background image intervals. Now that's the signpost name. Now if we hold down the option key and we zoom in, you can see there are intervals. And intervals are annotated with the start metadata and the end metadata.

Now if we zoom back out and then take a look at the trace here again, we'll notice that we have no more than five images that are running downloads in parallel, which is a good thing. That means that our cancellation worked. And if we want to confirm that, we can come in here and you can see that a lot of these intervals have metadata that says that it was cancelled in the download.

Now if you want to take -- if you want to look at a numerical -- or let's say you want to look at the durations of these intervals then you can come down here to the summary of intervals. And we see a breakdown by category and then by signpost name and then by the start message and then by the end message.

So if we make this a little bit smaller, you can see that we made 93 image download requests.

Of those, 12 were for location one.

Of those 12, seven were cancelled and five finished with a size of 3.31 megabytes.

Now if you look over here, these are the statistics about our durations. And you can see that the minimum and the average of the cancelled intervals is significantly smaller than when we finished with the full downloads. And that's exactly what you would expect to see in this pattern.

Now if you want to see all of the cancelled events because you're interested in seeing those, you can put this -- focus arrow and it will take you to a list view where you can see all the places where location one had an end message of cancelled.

And as we go through this, you'll see that the inspection head on the top of the trace will move forward to each one of those intervals. So you can track all the failure cases if that's what you're interested in. Now that's a great way to view the times of those intervals, the timing of those intervals. But what if you wanted to do an analysis of the metadata? What if you wanted to determine how many bytes of image data that we've downloaded over the network? Well, we've emitted metadata messages like finished with size and then the size. It would be great if we could total that argument up.

So if you want to do that, you can come over here to the summary of metadata statistics.

You can see that we have it broken down by the subsystem, the category, and then the format string and then below the format string, the arguments within that format string. And since our format string only has one, that's simply arg0. Now Instruments has totaled this up. And it knows that this is a size-in-bytes. And so it gives us a nice calculation of 80 megabytes. So we've downloaded 80 megabytes of image data total. Now you can see the different columns here. You've got it min, max, average, and standard deviation. So this is a great way to take a look at just statistical analysis of the values that you're conveying through your metadata.

Now Shane mentioned that signposts were very lightweight and that is totally true except when you run Instruments the way I just ran Instruments. In what we call immediate mode, which is the default recording mode, Instruments is trying to show and record the data in near real time.

And so when it goes into immediate mode recording, all the signposts have to be sent directly to Instruments. And we have to bypass all of those optimizations that you get from buffering in the operating system.

Now with our signposts -- with our signposts application here, we're not really emitting enough intervals to really notice that overhead, but if you have a game engine and you want to emit thousands of signposts per second, that overhead will start to build up. So in order to work around that, what you can do is change the recording mode of Instruments before you take your recording. And the way you do that is by holding down on the record button and selecting recording options.

And then in this section here for the global options, you can see that we have our immediate mode selected. And we can change that to last five second mode. Now this is often called windowed mode.

And what it tells the operating system and the recording technology is that we don't need every single event. We just want the last five seconds worth. And when you do that, Instruments will step out of the way and let the operating system do what it does. Now this is a very common mode. We use this in system trace. We use this in metal system trace and the new game performance template. And so it's a very common way to look for stutters and hangs in your application. All right.

So that is our os signpost instrument.

Now let's talk about points of interest.

Now if we come back to our Trailblazer application here, you notice that when I tap on a trail, it pushes a detail.

If I go back and tap on a different trail, it'll push a different detail.

Now it would be great if we could track every time these detail views come forward because then we can tell what our user is trying to do, and we can tell where our user is in the application.

Now you could certainly do this with a signpost, but you'd have to drag in the os signpost instrument and record all of the signpost activity on the application. And it sort of dilutes how important these user navigation events are.

So what we allow you to do is promote them to what are called points of interest.

Now if I go to our code for the detail controller and we look at our viewDidAppear method, you can see that I'm posting -- I'm creating an os signpost event saying that a detail appeared and with the name of the detail.

Now this is sent to a special log handle that we've created called points of interest. And the way that you create that is by creating a log handle with your subsystem identifier and the systems points of interest category. So this is a special category that Instruments will be looking for. And when it sees points here, it'll place them into the points of interest instrument. So if we come back here and take a time profile, you can see that we have our points of interest instrument automatically included. And if we do a recording and we do that same basic action, we go into the Matt Davis Trail and then we'll come back here to Skyline Trail and then we'll go back and we'll do one more for good measure.

Now when you go back to Instruments, you can see that we have those points of interest prominently displayed. So you can see where your user was in the navigation of your app. And you can correlate this with other performance data.

And so points of interest are really a way for you to pick and choose some of the most important points of interest in your application and make them available to every developer that's on your team or in your development community. And they can be seen right here in the points of interest.

All right. So that is the points of interest instrument and how you create points of interest from signposts.

Now another great feature of Instruments 10 is the ability for you to create custom instruments. And so to demonstrate what you can do with custom instruments in os signpost, we've created, as part of our project, a Trailblazer instruments package.

Now I'm going to build and run that now. And you'll see when we do that, we start a separate copy of Instruments that has our just built package installed. And if we bring that version forward, we'll see that we now have a Trailblazer networking trace template. And if we choose that, we can see that we have a Trailblazer networking instrument in our trace document.

And let's take a recording and see what the difference is between our points of interest or, I'm sorry, our os signpost and what this custom instrument can do. So we'll do the same type of thing. We'll do some basic downloading. And then we'll come back and we'll analyze our trace.

Now the presentation here is significantly different. So let's zoom in and take a look at it. You'll notice here on the left, instead of breaking it down by signpost name, we've broken it down by the image being downloaded. So now we can see that image two was downloaded at this point and at this point.

Now we've labeled each one with the size in megabytes of the download.

And we've also colored them red if the download size is larger than 3 1/2 megabytes.

So this is a custom graph that we created as part of our custom instrument. Now we've also defined some details down here. We've got a very simple list of our download events. And, again, you can navigate through the trace with those.

And we also have -- let me see if I can get this back into focus here. We also have a summary for all the downloads. Very simple. We just want to do a count and a sum. And then we also have this cool thing called Timeslice.

And in a Timeslice view, what we're trying to do is answer that question I was asking before of how many of these things are actually running in parallel? Well, if you want to take a look at the intervals running in parallel, you just scrub the inspection head over here through time, and you can see exactly what is intersecting that inspection head at any given point in time. So it's a great and a different way to look at your signpost data.

Now if you are working with others on a project or you're part of the development community, using a custom instrument is a great way to take the signpost data and reshape it in a way that someone else can use and interpret without having to know the details of how your code works so they are a very important feature. Now the great news is that to create an instrument like that, the entire package definition is about 115 lines of XML and so custom instruments is very expressive and very powerful but also very easy.

And that is the conclusion of our demo.

So in today's session, we took a look at the signpost API, and we showed you how to use it to annotate interesting periods of activity and intervals inside your application.

We showed you how to collect metadata and get that metadata into Instruments for visualization and analysis. And we showed you how to combine custom instruments in os signpost to create a more tailored presentation of your signpost data.

Now all this really comes down to us being able to give you the kind of information that you need to help you tune the performance of your application. And so we're really excited to see how you use os signpost and Instruments together to improve the user experience of your application.

That is the content for today. For more information, you can come see us in a lab, technology lab 8 at 3:00 today. And I also have session 410, creating custom instruments tomorrow where I'll be going over the details of how custom instruments works and show you how we created our Trailblazer networking instruments package.

Thank you very much. Enjoy the rest of your conference. [ Applause ]

-