-

Tune CPU job scheduling for Apple silicon games

Graphically-intensive games can be very demanding on hardware resources, requiring hundreds or even thousands of CPU jobs to be processed every frame. We'll show you how you can organize those jobs to maximize CPU efficiency and performance on the M1, M1 Pro, and M1 Max chips. Learn how you can fine-tune your games to deliver a better overall experience to your players.

Resources

-

Search this video…

Pierre Morf: Welcome to the session on how to tune CPU job scheduling for Apple silicon games. I'm Pierre Morf, working in the Metal Ecosystem team. I've been helping several third-party developers to optimize their GPU and CPU workloads on Apple platforms. With the help of the CoreOS team, I gathered here information and guidelines to achieve better CPU performance and efficiency in games. We are focusing on games, because they are usually highly demanding in terms of hardware resources. Also, their typical workload requires hundreds, if not thousands, of CPU jobs to be processed every frame. To get those done in 16 milliseconds or less, jobs must be tailored for maximum CPU throughput, and their submission overhead must be minimized. First, I'll go through an overview of the Apple silicon CPU and its unique architecture. Then, I'll provide you with fundamental guidance on how to organize your work to maximize the CPU efficiency. Finally, we'll discuss useful APIs to leverage, once those guidelines are implemented. Let's get started with the Apple CPU architecture. Apple has been designing its own chips for more than a decade. They are at the core of Apple devices. Apple silicon offers high performance and unmatched efficiency. Last year, Apple introduced the M1 chip. That was the first Apple silicon chip to be made available to Mac computers. And this year... ...we introduced M1 Pro, and M1 Max. Their new design is a huge leap for Apple silicon and makes them able to efficiently tackle very demanding workloads. The M1 chip gathers in a single package many components.

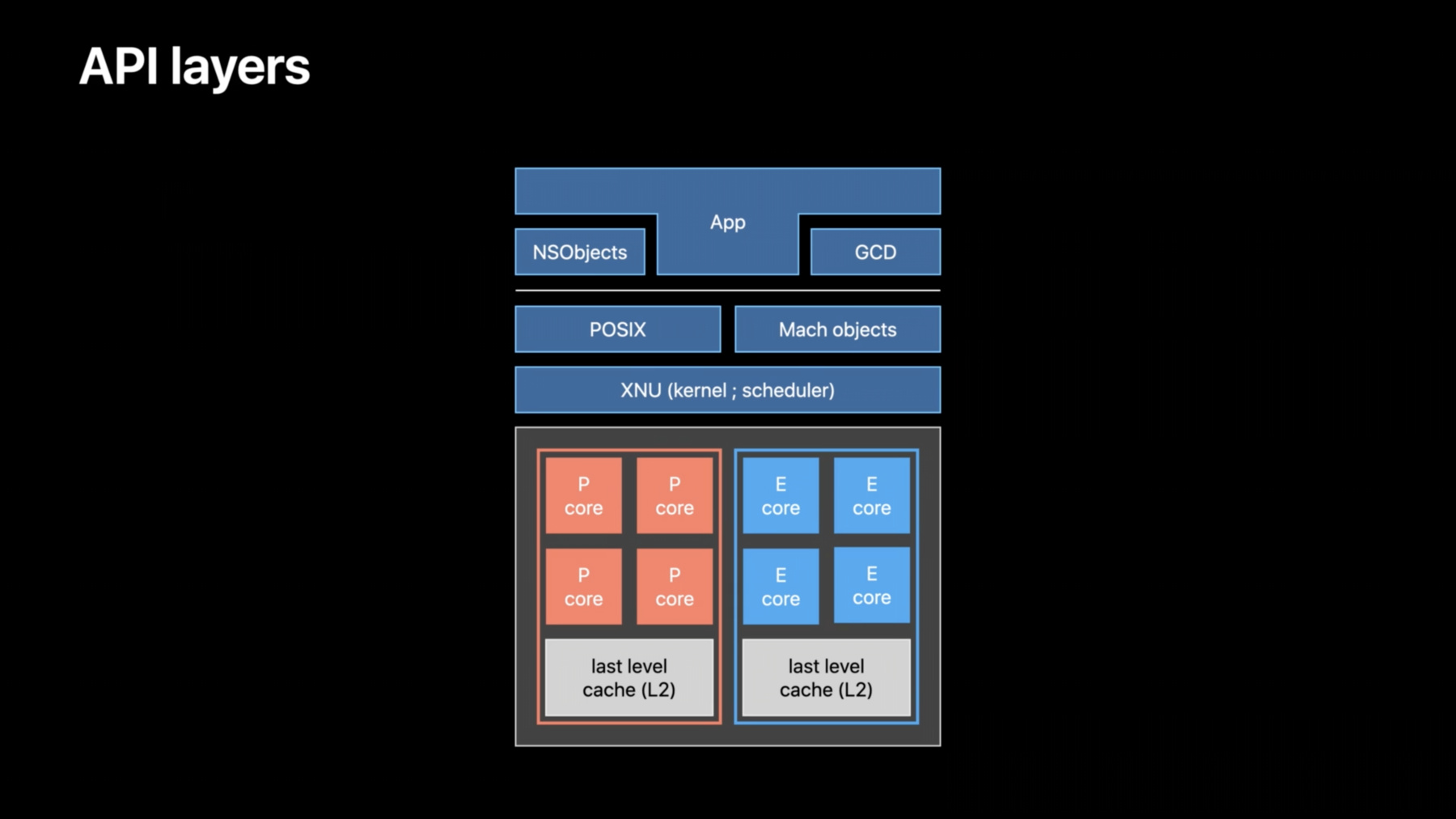

It contains a CPU, a GPU, Neural Engine, and many more. It also has a high-bandwidth, low-latency unified memory; it is accessible to all the chip's components through Apple Fabric. That means the CPU and GPU may work on the same data without copying it. Let's zoom into the CPU. On M1, the CPU contains cores of two different types: the performance cores and the efficiency cores. Those are physically different, the E cores being smaller. The efficiency cores are meant to process work with a very low energy consumption. There is a very important takeaway point: the P and E cores use a similar microarchitecture, which is really their inner working. They've been designed so that developers don't need to care whether a thread runs on a P or E core. If a program is optimized to perform well on a type of core, it is expected to perform well on the other. Those cores are physically grouped together into clusters, at least according to their type. On M1, each cluster has a last level cache -- a L2 -- shared by all of its cores. Cross-cluster communication goes through Apple Fabric. The CPU topology shown here is specific to the M1 chip. Other devices may have a different CPU layout. For example, an iPhone XS has one cluster of two P cores, and one cluster of four E cores. This architecture allows the system to optimize for performance when needed or to optimize for efficiency instead, improving the battery life, when performance is not a priority. Each cluster may be independently activated or have its frequency adjusted by the kernel's scheduler -- depending on the current workload, the current thermal pressure for that cluster, and other factors. Finally, note the availability of P cores is not guaranteed. The system reserves the right to make them unavailable under critical thermal scenarios. Here is an overview of the different API layers interacting with the CPU. First we have XNU -- the kernel running macOS and iOS. That is where the scheduler lives, deciding what runs on the CPU and when. On top of it, we have two libraries: POSIX with pthreads and Mach objects. They both provide fundamental threading and synchronization primitives to the application. On top of that we have higher-level libraries. Thread-related NSObjects encapsulate POSIX handles. In example, an NSLock encapsulates a pthread_mutex_lock, a NSThread encapsulates a pthread, among other things. That is also where GCD sits. GCD is an advanced job manager. We will cover it later. In this session, we will work our way up starting from the low level, finishing with API features. Let's start by focusing on what works best for the CPU, and how to lighten the workload put on the scheduler. This will be our fundamental efficiency guidelines. They apply to any job manager implementation, are API-agnostic, and apply to many platforms -- including both Apple silicon and Intel-based Macs. Let's imagine we are in an ideal world and we have this job. If we spread it over four cores, it should be processed exactly four times quicker, right? Unfortunately, that's not as straightforward in a real CPU. There are many bookkeeping operations going on, each costing some execution time. There should be three costs to keep in mind for efficiency. Look at the cores 1, 2, and 3. They were not doing anything before processing our job. Well, when a CPU core has nothing to do for quite some time, it goes idle to save energy. And reactivating an idle core takes a little bit of time. That is our first cost, the core wake-up cost. Here is another one. CPU work is first initiated by the OS scheduler. It decides which process and thread should be running next, and on which core. The CPU core then switches to that execution context. We'll call that the scheduling cost. Now, the third and last type of cost. Let's consider the thread running on Core 0 signals the ones on cores 1, 2, and 3. For example, with a semaphore. That signaling is not instantaneous. During this interval, the kernel has to identify which thread is waiting on the primitive; and in case the thread was not active, it needs to schedule it. This delay is called the synchronization latency. Those costs appear, in one form or another, in most CPU architectures. They are not an issue by themselves, as they are very, very short. But they may become a performance hit if they accumulate, appearing repeatedly and frequently. What do those costs look like in real life? This is an instruments trace of a game running on M1. That game exhibits a problematic pattern, repeated most of its frames. It tries to parallelize jobs at an extremely fine granularity. We already zoomed a lot into its timeline. To give you an idea, that section only takes 18 microseconds. Let's focus on that CPU core, and those two threads. Those two threads could have been running in parallel, but they ended up running serially on that same core. Let's see why. They synchronize with each other very often. The first one signals the second one to start and very quickly waits for its peer to be done. The second starts working, quickly signals the first one, and waits very shortly after. This pattern repeats over and over. We can see two issues here: first, synchronization primitives are used at an extremely high frequency. That interrupts work and introduces overhead. We can see that overhead with the red sections. Second, the active work -- the blue sections -- is extremely brief. it only lasts between four and 20 microseconds. This duration is so small, it is barely shorter than the time it takes to wake up a CPU core. During those red sections, the OS scheduler was mostly waiting for a CPU core to wake up. But right before that happens, a thread blocks and frees up the core. The second thread then runs on that same core instead of waiting a little bit longer for another one to wake up. That's how those two threads lost a tiny opportunity to run in parallel. Just from this observation, we can already define two guidelines. First, choose the right job granularity. We can achieve it by merging tiny jobs into larger ones. Scheduling a thread takes a little bit of time, no matter what. If a job becomes tiny, the scheduling cost will take a relatively larger part of the thread's timeline. The CPU will be underutilized. On the contrary, larger jobs amortize the scheduling cost by running for longer. We have seen a professional application -- submitting lots of 30-microseconds work items -- drastically increasing their performance when they merged them. Second, line up enough work before leveraging threads. This can be done every frame, by getting most jobs ready at once. When you signal and wait for threads, that generally means some will be scheduled on the CPU core and some will be blocked and moved off core. Doing that many times is a performance pitfall. Waking and pausing threads repeatedly adds more of the costs we just talked about. Conversely, making threads process more jobs without interruption removes synchronization points. As an example, when dealing with nested for-loops, it is a much better idea to parallelize the outer for at a coarser granularity. That leaves the inner loops uninterrupted. That gives them a better coherency, a better cache utilization, and overall, fewer of those synchronization points. Before leveraging more threads, determine if it is worth the cost. Let's now have a look at another game trace. That one was running on an iPhone XS. We'll focus on those helper threads. We can see the synchronization latency here. This is the time it took the kernel to signal those different helpers. There are two issues here: first, the actual work is extremely small again -- roughly 11 microseconds -- especially in comparison to the entire overhead. Merging those jobs together would have been more energy efficient. Second issue: in that timespan, 80 different threads were scheduled on three cores. We can see context switches here, those tiny gaps between active work. In this example, it isn't a problem yet -- but with more threads, context switching time may accumulate and hinder the CPU performance. How can we minimize all those different kinds of overhead when a typical game has at least hundreds of jobs every frame? The best way of doing so is by using a job pool. Worker threads consume them through job stealing. Scheduling a thread is done by the kernel; we saw it takes some time. And the CPU also has to do some work, like context switching. On the other hand, starting a new job in user-space is much cheaper. Generally, a worker just has to decrement an atomic counter, and grab a pointer to a job. Second point: avoid interacting with predetermined threads, since using workers will reduce the amount of context switches. And as they grab more jobs, you leverage an already active thread on an already active core. Finally, use your pool wisely. Wake up just enough workers for the work being queued up. And the previous rule applies here too: ensure enough work is lined up to justify waking a worker thread, and keeping it busy. We reduced our overhead; now, we must make the most out of our CPU cycles. Here are some patterns to avoid. Avoid busy waits. They potentially lock a P core, instead of doing something useful with it. They also prevents the scheduler from promoting a thread from and E to a P core. You are also wasting energy and producing unnecessary heat, eating away your thermal headroom. Second, the definition of the yield function is loose across platforms and even OSes. On Apple platforms, it means, "try to cede the core I'm running on to any other thread on the system, anything else, whatever their priority is." It effectively tanks the current thread priority to zero. A yield also has a system-defined duration. It may be very long -- up to 10 milliseconds. Third, calls to sleep are discouraged as well. Waiting for a specific event is much more efficient. Also, note on Apple platforms, sleep(0) has a no meaning and that call is even discarded. Those patterns are generally a sign a fundamental scheduling error happened in the first place. Instead, wait on explicit signals with a semaphore or a conditional variable. Final guideline: scale the thread count to match the CPU core count. Avoid recreating new thread pools in each framework or middleware you are using. Do not scale your thread count based on your workload either. If your workload increases dramatically, so will your thread count. Instead, query CPU information to size your thread pool appropriately, and maximize parallelization opportunities for the current system. Let's see how to query this information. Starting with macOS Monterey and iOS 15, you can query advanced details about the CPU layout with the sysctl interface. In addition to get an overall count of all CPU cores, you can now query how many types of cores a machine has with nperflevels. On M1, we have two types of cores: P and E. Use this range to query data per core type, zero being the most performant. For example, perflevel{N}.logicalcpu tells how many P cores the current CPU has. This is just an overview. You can also query many other details, like how many cores share the same L2. For more details, refer to the sysctl man page, or the documentation webpage. When profiling your CPU usage, two instruments tracks are very useful. They are available in the Game Performance template. The first one, System Load, gives the number of active threads per CPU core. The second one is Thread State Trace. By default, the detail pane shows the amount of thread state changes and their duration per process. It can be changed to the Context Switches view. This will give you a count of context switches per process in the selected time range. Context switches count is a useful metric to measure an app's scheduling efficiency. Let's close on this section. By following those guidelines, you will make the most out of the CPU and streamline what the scheduler has to do. Compacting tiny, tiny jobs into longer running ones increases the benefits of microarchitectural features, like caches, prefetchers, and predictors. Processing more jobs at once means less interrupt latency and context switches. An appropriately scaled thread pool makes it easier for the scheduler to rebalance work between E and P cores. A key take-away for efficiency and performance is to minimize the frequency at which your workload is going wide and narrow. Let's now dive into which API blocks you can leverage while applying those guidelines. In this section, we'll cover prioritization and scheduling policies, synchronization primitives, and memory considerations when multithreading. But first, let's start by having a sneak peek at GCD. If you don't have a job manager, or if it doesn't reach the high performance you are aiming for, GCD is a fantastic choice. It is a general-purpose job manager using job stealing. It is available on all Apple platforms and Linux, and it is open source. This API is highly optimized. First, it already follows all the best practices for you. Second, it is integrated in the XNU kernel. That means GCD may keep track of internal details for you, like the heat dissipation capacity of the current machine, its P/E core ratio, the current thermal pressure and so on. Its interface relies on serial and concurrent dispatch queues. You can enqueue jobs in them with varying priorities. Internally, each dispatch queue leverages a variable amount of threads from a private thread pool. That number depends on the type of queue and job properties. This internal thread pool is shared for the entire process. That means in a given process, multiple libraries may use GCD without recreating a new pool. GCD offers many features. Here we'll quickly review just two functions from the concurrent dispatch queues, just to get a sense of how it works. The first one, dispatch_async, allows you to enqueue a job made of a function pointer and a data pointer. When starting a job, the concurrent queue may leverage an additional thread if the next job in line is also ready to be processed. That is a great option for typical asynchronous independent jobs. But not so much for massively parallel problems. In that case, there is dispatch_apply. That one will leverage many threads right from the start, without overloading GCD's thread manager. We have seen several pro apps increasing their performance by migrating a parallel for to using dispatch_apply. That was just a quick overview of GCD. To learn more about it and which patterns to avoid, refer to those two WWDC sessions.

Let's now switch to custom job managers. We'll cover the most important points when manipulating threads directly and synchronizing them. Let's begin with prioritization. In the previous section, we reviewed how to increase the CPU efficiency when submitting jobs. But so far, we had not mentioned that all jobs are not equal. Some are time-critical, their result is needed as soon as possible. And some other will only be required in the next frame or two. So it is necessary to convey a sense of importance when processing your jobs to give more resources to the more important ones. That can be done by prioritizing your threads. Setting the right thread priorities also informs the system your game is more important than background activity. This can be achieved by setting a thread with either a raw CPU priority value or a QoS class. Both concepts are related, yet slightly different. A raw CPU priority is an integer value telling how important computational throughput is. On Apple platforms, contrary to Linux, this is an ascending value -- the higher, the more important. This CPU priority also hints -- among other factors -- at whether a thread should run on a P or E core. Now, this CPU priority doesn't affect the rest of system resources since it doesn't give any intention about what the thread is doing. Threads can instead be prioritized with Quality of Service -- QoS for short. QoS has been designed to attach semantics to threads. This intention greatly helps the scheduler to make intelligent decisions about when to execute tasks, and makes the OS more responsive. For example, a lower importance task may be slightly deferred in time in order to save energy. It also allows to prioritize system resources access like network, disk access. It also provides thresholds for timer coalescing -- an energy-saving feature. QoS classes also include a CPU priority. There are five QoS classes, going from QOS_CLASS_BACKGROUND, the least important one, to QOS_CLASS_USER_INTERACTIVE, the highest one. Each includes a default CPU priority. Optionally, you may slightly downgrade it within a limited range. This is useful if you want to finely tweak the CPU priority for several threads opting into the same QoS class. Note to be very careful with the Background class -- threads using it may not run at all for a very long time. So overall, games use CPU priorities ranging from 5 to 47. Let's see how that's done in practice. First, you need to allocate and initialize the pthread attributes with default values. You then set the required QoS class and then pass those attributes to the pthread_create function. Finish by destroying the attributes structure. You can also set a QoS class to an already existing thread. As an example, that function affects the calling thread. Note here, we used an offset of -5, downgrading the class CPU priority from 47 to 42. Note you can see the np suffix in the function names. That stands for "nonportable"; it's a naming convention used for functions exclusive to Apple platforms. Finally, beware that if instead of using those functions, you directly set a raw CPU priority value, you opt out of QoS for that thread. That is permanent, and you cannot opt back in QoS for that thread afterwards. iOS and macOS deal with many processes, user-facing or running in the background. In some cases, the system may become overloaded. If that happens, the kernel needs a way to ensure all threads get a chance to run at some point. That is done with priority decay. In this special case, the kernel slowly lowers thread priorities over time; all threads then have a chance to run. Priority decay may be problematic in very special cases. Typically, games have a couple of highly critical threads, like the main thread and the render thread. If the render thread gets preempted, you may miss a presentation window, and the game will stutter. In those cases, you can opt out of priority decay with scheduling policies. By default, threads a created with the SCHED_OTHER policy. This is a time-sharing policy. Threads using it may be subject to priority decay. It is also compatible with QoS classes we presented before. On the other hand, we have the optional SCHED_RR policy. RR stands for "round-robin". Threads opting into it have a fixed priority unaffected by priority decay. It offers a better consistency in execution latency. Note it is exclusively designed for consistent, periodic, and high-priority work, for example, a dedicated render thread or per-frame worker threads. Threads opting into it must work on a very specific time window, and not continuously busy the CPU 100 percent of the time. Using this policy may also lead to starvation in your other threads. Finally, this policy is incompatible with QoS classes -- threads will need to use a raw CPU priority. Here is a recommended layout for game threads. First, define within your game what is high-, medium- and low-priority and what is critical to the user experience. Splitting work by priority lets the system know which parts of your application are the most important. Use instruments to profile your game, and only opt into SCHED_RR for the threads which actually need it. Also, never use SCHED_RR for a long duration work, extending multiple frames. Rely on QoS in those cases to help the system balance performance with other processes. Another reason to favor opting into QoS is when a thread interacts with Apple frameworks like GCD or NSOperationQueues. Those frameworks try to propagate the QoS class from the job issuer into the job itself. That is obviously ignored if the issuing thread has abandoned QoS. Let's cover one last point related to priorities: priority inversion. Priority inversion happens when a high-priority thread stalls, being blocking by a low-priority thread. This typically happens with mutual exclusions. Two threads try to access the same resource, fighting to get the same lock. In some cases, the system may be able to resolve this inversion by boosting the low-priority thread. Let's see how that works. Let's consider two threads -- here are their execution timeline. In this example, the blue thread is low priority, the green one is high priority. In the middle, we have the lock timeline, showing which of the two threads will own that lock. The blue thread starts executing, and acquires the lock. The green thread also starts. At this point, the green thread tries to acquire that lock, currently owned by the blue thread. The green thread blocks and waits for that lock to be available again. In this case, the runtime can tell which thread owns that lock. Therefore, it can resolve the priority inversion, by boosting the blue thread's low priority. Which primitives have the ability to resolve priority inversion and which ones don't? Symmetric primitives with a single known owner can do that, like pthread_mutex_t or the most efficient, os_unfair_lock. Asymmetric primitives like pthread conditional variables or dispatch_semaphore don't have this ability, because the runtime doesn't know which thread will signal it. Keep this feature in mind when choosing a synchronization primitive, and favor symmetric primitives for mutually exclusive access. To finish this section, let's discuss a couple of recommendations about memory. When interacting with Objective-C frameworks, some objects are created as autorelease. That means they are added to a list, so that their deallocation only happens at a later time. Autorelease pool blocks are scopes limiting how long such objects can be kept around. They effectively help reducing the peak memory footprint of your app. It is important to have at least one autorelease pool, in every thread entry point. If any thread manipulates autoreleased objects -- for example, through Metal -- without one, that will lead to memory leaks. Autorelease pool blocks can be nested, to better control when memory is recycled. The render thread should ideally create a second one around the repeated frame rendering routine. Worker threads should have a second one starting on activation and closed as the worker gets parked, waiting for more work. Let's see an example. This is a worker thread entry point. It starts right away with an autorelease pool block. It then waits for jobs to be available. When the worker gets activated, we add a new autorelease pool block, and keep it around as we process jobs. When the thread is about to wait and be parked, we exit the nested pool. To conclude, one quick tip about memory. To improve performance, avoid having multiple threads simultaneously write data located in the same cache line. That is known as "false sharing". Multiple reads from the same data structure is fine, but such competing writes lead to ping-ponging that cache line between different hardware caches. On Apple silicon, a cache line is 128 bytes long. One solution to this is inserting padding within your data structure to reduce memory conflicts. We are done with this last section. Let's wrap up. We first got an overview of the Apple CPU architecture, and how its groundbreaking design makes it much more efficient. Then, we got into how to feed the CPU efficiently and make it run smoothly while reducing the load put on the OS scheduler. We finally reviewed important API concepts, such as thread prioritization, scheduling policies, priority inversion, finishing with tips about memory. Don't forget to regularly profile your game with instruments to keep an eye on its workload, so you can spot performance issues early. Thank you for your attention.

-